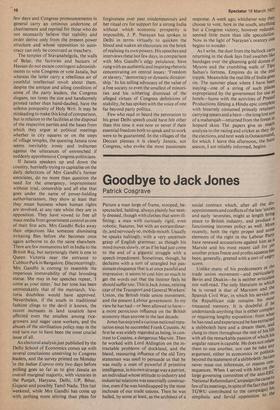

The devil they know

Alan Ross

Mysore Summer has come early this year and with it the mosquitoes. The south of India has always been neglected, not least by the British since they finally overcame Tipu Sultan near here at Seringapatam and sensibly left the vanquished to their own devices and in the hands of their own mostly enlightened maharajas. Nevertheless Mrs Gandhi felt it necessary to pass this way last week and alight briefly from her aeroplane, addressing meetings in various cities before winging her way back to more serious business in the north. Whether she made much impact other than by the show of her presence is another matter. In her wake Congress politicians and their entourages have travelled the countryside, loudspeakers blaring, disrupting the rural calm of this most reflective and beautiful landscape where always in the middle distance women in blue or green saris are picking the rice or swaying along dusty roads with gleaming brass vessels on their heads. But summer has beaten them to it. Most of the roads here are made up to only the width of one vehicle, so that, driving along, there is always the moment of confrontation when two approaching objects meet, whether truck, bus, car, bullockcart or bicycle. Indeed there could be no more telling image of relevant values than this morning outside Seringapatam when a Congress car, flags streaming in the dust ahead of us, had to give way to a stately bullock-cart, its driver plodding serenely on his way under a black umbrella, indifferent to all exhortation.

It may be different among the voluble Marxists of Kerala to the west of us, or among the eloquent Bengalis of my own childhood to the north-east, but here on the burning plains of M.ysore the bullockcart reigns supreme. Of course this is not the whole story but such evidence as there is of political ferment in the cities and villages of Kanataka seems largely contrived, and whatever happens next week is likely to appear secondary to the daily rituals of agriculture and in the end illusory.

Slogans have never been in short supply in India, whether paternalistically exhortatory as in the Congress messages leaping from hoardings all over the country so that after a while one begins to feel one is in Soviet Russia, 'Discipline ensures Progress,' or the moral homilies visible on the backs of the eight thousand autorickshaws in Bangalore, 'Work more, talk less.' Every governmental building carries some simple inducement to smile or be courteous or be clean. That is nothing new. But Mrs Gandhi's interviews and sp'eeches these last

few days and Congress pronouncements in general carry an ominous undertone of chastisement and reprisal for those who do not necessarily believe that stability and order derive only from the present power structure and whose opposition to autocracy can only be construed as treachery.

The temples of Sravanabelgola, the walls of Belur, the factories and bazaars of Hassan do not escape contingent admonishments to vote Congress or vote Janata, but whereas the latter carry a rebellious air of youthful intellectual revolt about them, despite the antique and ailing condition of some of the party leaders, the Congress slogans, ten times the size and handsomely printed rather than hand-daubed, have the solemn pomposity of Holy Writ. It may be misleading to make this kind of comparison, but in relation to the facilities at the disposal of the respective parties and the bases from which they argue at political meetings whether in city squares or on the steps of village temples, the questing Janata tone seems inevitably ironic and indiscreet against the utterances of entrenched if suddenly apprehensive Congress politicians.

If Janata speakers up and down the country, hurriedly trying to capitalise on the daily defections of Mrs Gandhi's former associates, do no more than question the need for the emergency, imprisonment without trial, censorship and all else that goes under the name of power-holding authoritarianism, they show at least that they mean business where human rights are involved, at any rate whilst they are in opposition. They have vowed to free all mass media from government control as one of their first acts, Mrs Gandhi flicks away their objections like someone dismissing irritating flies before she becomes once again airborne to do the same elsewhere. There are few monuments left in India to the British Raj, but surprisingly there is one to Queen Victoria near the entrance to Cubbon Park in Bangalore. Disconcertingly, Mrs Gandhi is coming to resemble the imperious immovability of that brooding statue. She may in her speeches repeat, 'I come as your sister,' but her tone has been unmistakably that of the matriarch. Victoria doubtless would have approved. Nevertheless, if the south in traditional fashion clings to the devil it knows, the recent increases in land taxation have affected even the smallest among ricegrowers and sugar cane workers, and the abuses of the sterilisation policy may in the end turn out to have been the most crucial issue of all.

An electoral analysis just published by the Delhi School of Economics comes up with several conclusions unnerving to Congress leaders, and the survey printed oft Monday in the Indian Express only two days before polling goes so far as to give Janata an overall marginal majority, with victories in the Punjab, Haryana, Delhi, UP, Bihar, Gujarat and possibly Tamil Nadu. This last weekend, while Mrs Gandhi has come up with nothing more stirring than pleas for forgiveness over past misdemeanours and her ritual cry for support for a strong India without which economic prosperity is impossible, J. P. Narayan has spoken in Delhi in terms virtually to quicken the blood and waken an electorate on the brink of realising its own powers. H is speeches and interviews these last few days, in comparison with Mrs Gandhi's edgy petulance, have rung with an authentic and inspiring rhetoric concentrating on central issues: 'Freedom or slavery,' democracy or dynastic dictatorship.' In his telling advocacy of the value of' a free society to even the smallest of minorities and his withering dismissal of the alleged virtues of Congress definitions of stability, he has spoken with the voice of one far beyond party politics.

Few who read or heard the peroration to his great Delhi speech could have felt other than this time it was now or never if their essential freedom both to speak and to work were to be guaranteed. In the villages of the Deccan plateau it is clearly Janata, not Congress, who evoke the most passionate

response. A week ago, whichever way they choose to vote, here in the south, anything but a Congress victory, however reduced, seemed little more than idle speculation. Now in the light of Narayan's oratory one begins to wonder.

As I write, the dust from the bullock carts returning in the dusk lays frail swathes like bandages over the gleaming gold domes of Mysore and the crumbling walls of T1130 Sultan's fortress. Empires do in the end topple. Meanwhile the real life of India goes on. The summer place where I have been staying—one of a string of such places expropriated by the government for use as hotels—hums with the activities of Prasad Productions filming a Hindu epic complete with bizarrely costumed princely retainers carrying spears and a hero—the long lost son of a maharajah—returned from the forest in leopard skins The papers give as much analysis to the racing and cricket as they d° the elections, and next week in Ootacamund, for which I leave this afternoon, the hunt season, I am reliably informed, begins.

Previous page

Previous page