`CONSERVATISM IS NOT OVER'

Simon Sebag-Montefiore finds William F. Buckley wistfully recalling the Reagan years

New York WILLIAM F. Buckley was once the seer who faced the enviable curse of seeing all his prayers answered. Now, in 1990, fashion has spurned her old favourite. For over 30 years, Buckley was the good- looking, well-bred and monied face of right-wing radicalism in America. The name of the novel that made him famous when he was only 24, God and Man at Yale, suggests the way he saw himself and the American dream. The young novelist, the journalist who created the magazine the National Review and the long-serving host of the television chat show Firing Line had shocked, argued and charmed for Conservatism from the paranoid Fifties, through the liberal Sixties and the jaded Seventies until 1981, when God and man at last joined forces to place Buckley's veter- an admirer in the White House. America had made a sharp right turn and Ronald Reagan came to power with a landslide and a radical conservative programme. At last, Buckley was given the credit for all his work. 'You did not just part the Red Sea. You rolled it back and left exposed for all to see the naked desert that is statism,' declared the histrionic and newly re- elected President at the December 1985 dinner for his patrician political muse. The

dinner was Buckley's swan song. He was the ideological conscience of Reagan's imperial White House.

Today in 1990, that peak is past: the books are not selling so well; the Firing Line is no longer in the front line of the ideological battle; the syndicated columns are as provocative as they are light, with- out the authority of a George Will or a William Safire. They read like Walter Lippmann on opium. And the times have changed too. The President is a Republi- can pragmatist, not as bad as a liberal, but bad nonetheless. Lastly, with a disintegrat- ing Russian empire, a free Eastern Europe and democracy in Nicaragua, the cockpit of conservatism, the battle seems won: what happens to old warriors? Buckley is suspended between National Treasure and National Bore. Will he remain one of the lions — or will he be fed to them?

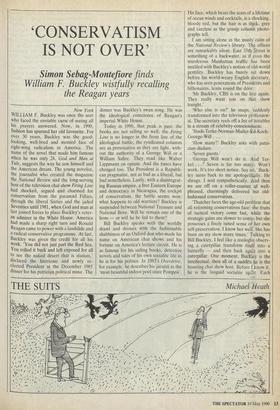

Bill Buckley speaks with the worldly drawl and dresses with the fashionable shabbiness of an Oxford don who made his name on American chat shows and his fortune on America's lecture circuit. He is as famous for his sailing books, detective novels and tales of his own socialite life as he is for his politics. In 1983's Overdrive, for example, he describes his jacuzzi as the `most beautiful indoor pool since Pompeii'.

His face, which bears the scars of a lifetime of ocean winds and cocktails, is a shocking, bloody red, but the hair is as th,ick , grey and careless as the gossip column photo- graphs tell.

I am sitting alone in the musty calm of the National Review's library. The offices

are remarkably silent. East 35th Street is something of a backwater, as if even the murderous Manhattan traffic has been instilled with Buckley's notion of old-world gentility. Buckley has barely sat down before his world-weary English secretary, who has seen generations of Presidents and billionaires, leans round the door: 'Mr Buckley, CBS is on the line again. They really want you on that show tonight.'

'Who else is on?' he snaps, suddenly transformed into the television profession- al. The secretary reels off a list of notables in a stream of celebrity-consciousness:

`Studs-Terke-Norman-Mailer-U-Koch- George-Will . . .

`How many?' Buckley asks with patri- cian disdain.

`Seven guests.'

`George Will won't do it. Rind Ter- kel . . .? Seven is far too many. Won't work. It's too short notice. Say no.' Buck- ley turns back to me apologetitally. He shrugs. I nod sympathetically. And then

we are off on a roller-coaster of well- phrased, charmingly delivered 0 but old- fashioned conservatism.

'Thatcher faces the age-old problem that all reforming conservatives face: the fruits of tactical victory come fast, while the

strategic gains are slower to comet but she possesses a finely tuned sense of her own

self-preservation. I know her well. She has

been on my show many times.' talking to Bill Buckley, I feel like a zoologist observ-

ing a caterpillar transform itself into a butterfly — and then back again into a caterpillar. One moment, Buckley is the intellectual, then all of a sudden. he is the boasting chat show host. Before I know it, he is the languid socialite again. Each manifestation discredits the one before.

George Bush is a sensitive subject with Bill Buckley: after all, when the writer was limousining into the White House to deliv- er conservative wisdom to his innocent but aging pupil during Reagan's glory days, the Vice-President was a minor if not pathetic figure on the sidelines. Is Bush the be- trayer of the Reagan revolution? My sub- ject watches his words carefully: 'They were right when they said George is conservative, not a Conservative.'

`So, does Bush mean the end of conser- vatism?'

'Oh no. Conservatism is not over. The Eighties altered the definition of politics. Reagan changed the nature of economic thought — do not castigate yourself by chopping off the heads of the productive people.'

If George Bush's unparalleled popular- ity ratings suggest that Americans appreci- ate his cautious, courteous and compromis- ing style even more than they admired Reagan's hardline conservatism, Buckley is clear which makes the better president: 'Reagan had an inbuilt sense of priorities and does not like to dislodge them. These are good qualities in a democratic adminis- trator. He made mistakes, but at the crunch he always did the right thing. I would say he was one of the two or three most effective presidents of the 20th cen- tury.'

History will find it a difficult comparison to make: in the Reagan era, America walked tall again, while in Bush's presiden- cy the collapse of the Soviet bloc seems to have justified his relaxed and undefined foreign policy.

`There are two criteria for judging an era: what ideally should it have been like, and how close was it, given reality? If the ideal is 100, Reagan gets 90.' He paused.

'He is a very close friend. He is now on the Board of the National Review.' Strangely, Buckley has always appealed more to the glitzy, nouveau-riche characters of Reagan's coterie than to Bush's circle of traditional upper-class Americans, who find him rather slick and showy. Buckley, who sees himself at the heart of America's Catholic aristocracy (he is a WASC, not a WASP), loved Reagan's policy but found the razzmatazz too vulgar. Yet who else but the populist Gipper could have sold a decade of conservatism to the masses?

Given that fear of communism obsessed America for 70 years and was the spur of conservatism (as a young man during the witch-hunts of the Fifties Buckley was a campaigner on behalf of Joe McCarthy), did Buckley never want to take office and turn his words into action?

`As one gets older, one has to decide whether to be a critic or a statesman. In Britain, you can be both, but not in America. I wrote to Reagan in June 1980 to say I desired no position in his cabinet. When he won, he offered me the ambassa- dorship to Afghanistan. I said, 'Yes, but only if you give me 15 divisions of body- guards.' I was offered the United Nations and I said no. It is an illusion that you need to be a formal member of government to have real power. The owner of the New York Times has far more power than both the state's senators.'

Before I could point out that the Nation- al Review was not the New York Times, we

moved on to the question of the under- class. With communism fast disappearing, the underclass and the social role of govern- ment is one of the last traditional conser- vative issues. As we discussed it, I realised that Renaissance man Buckley had travelled far beyond argument into that short list of evergreen celebrities who are one-man industries with newspaper columns, chat shows, novels, magazines: we know they are great American figures, but we are no longer sure exactly why. Buckley is so high that he is able to deny the very existence of the poor, the thousands of blacks and Hispanics begging, ranting and tripping on the city streets.

Even with a black mayor, New York is obsessed with race, drugs and the under- class. In the last few weeks, there have been demonstrations in Harlem because the police had shot 17 people in a month, most of them black or Hispanic. Recent figures show that one quarter of young blacks in New York have been in prison by the age of 25. Television anchorman Andrew Rooney was recently suspended after suggesting that the black underclass was the result of 'a watering down of the genes'. From my bedroom window in Greenwich Village, I am fascinated every day to watch the brisk market of drugs and stolen goods in the street bazaar stretching down Astor Place into St Marks and the occasional raids by undercover agents wav- ing pistols and handcuffs. What was Amer- ica to do about a class existing on a crack economy without sharing in the ideals of 1 can handle the dark night of the soul — it's the dark lunchtime that's getting to me.' `God and man' that created America? Buckley is unimpressed by such liberal twaddle: `You know there is a high degree of mobility amongst these people. There aren't many of them.'

`Shouldn't there be subsidies?'

Buckley looked at me kindly as if I were a misguided child.

`Maybe it's because I am English, but.

`Even if you proved that subsidies were actually damaging, an Englishman would still believe in them,' said Buckley.

:If you ignore them too long, maybe they will rise up . . . I said, almost enjoying the idea.

`They have nothing to revolt against. A democracy is resilient enough to absorb these people. Revolutions only arise against closed societies. Teddy Roosevelt's Attorney-General was once told that the German-born population was liable to rise In revolt if America ever turned against imperial Germany. He said, "How many Germans are there in America?" "100,000," he was told. I would quote his answer in this context. "Fine," he said. "We have more than 100,000 lampposts!"'

Previous page

Previous page