Sale-rooms

No books please,

we're British

Peter Watson

With the ever-increasing ascendancy of the auction houses, diatribes from the dealers are becoming as frequent as hazard warning lights or contra-flow systems on the MI. One set of gripes, however, cannot be laid at the door of the gavel gang and, for that reason, appears all the more noteworthy. It relates to the startling col- lapse of the British as book collectors.

A month from now, in the third week of June, the London Book Fair will be held. To coincide with this, Sotheby's is holding a large sale of atlases, travel and history books. This will include works from no fewer than four great British collections those of the Marquess of Downshire, the Rt Hon the Lord de Saumarez, Lt-Col Sir John Miller, and atlases from the well- known firm of John Bartholomew of Edin- burgh. For the antiquarian book trade, there is a bitter lopsidedness to a sale such as this one. For, as these great collections are dispersed they are not being replaced — at least, not by British collectors.

The collapse in book collecting is con- fined, for the moment, to antiquarian books: there are not a few souls who, like Mr Kenneth Baker, spend their pennies on modern first editions. But, whereas there is no shortage of young Continental or American collectors of 16th-, 17th- and 18th-century books, the British have, in the past few years, become noticeable by their absence. Some antiquarian booksel- lers tell me that they have no serious British collectors under the age of 50.

The reasons for this state of affairs are not easy to adduce. Finance is not one of them. Greater fortunes than ever have been made during the period of this decline and Britain has not lagged noticeably behind either the Continent or America in this regard. Collecting, as such, has not declined — if anything it has expanded in

the realm of pictures and objets d'art.

Can the collapse be put down to a fall in standards of literacy? This seems unlikely: the decline would have to be near total to have an effect on the collecting classes. In any case, if that argument applied, it would surely apply a fortiori in the United States where, if reports are to be believed, standards of literacy have fallen even further. Yet the Americans still collect.

It is not that objects have not been available to collect. On the contrary, from the Houghton sale in 1980 to the Bradley Martin sales of the past few months, the market has seen some of the finest material under the hammer. This is borne out by the fact that institutional buying — including British institutional buying — is as strong as ever. Indeed, this strong institutional presence in the market only adds to the paradox.

One bookseller I spoke to puts it down to television programmes like The Anti- ques Roadshow, which, he suggests, pro- motes in the British a 'selling' rather than an 'acquisitive' mentality. I don't believe this can be a fundamental reason though it may be a factor. The Antiques Roadshow hardly ever deals with books and the collapse seen in book collecting is not paralleled in other areas featured by the programme.

Perhaps a better way of understanding this startling trend is to see it as the verso to the recto of Impressionist collecting, which has grown so much. In the art market, the 1980s have surely been, if nothing else, a decade of conspicuous consumption. It was a time when a Utrillo, a Chagall or a Vlaminck were worth throwing money at simply because the image was instantly recognisable. A Re- noir is as distinctive a brand as a Renault, a Vuillard travels as well as Vuitton. Books could not be more different. They are far more introverted objects; it is not im- mediately clear whether that unlettered calf on your shelves is worth £25 or £250,000. And it may not be all that obvious when you take it down and open it, either.

Of course, the decline may be due to something more serious, more fun- damental. The Japanese are avid collectors of John Locke and are apparently willing to see the importance of his ideas even today. Our readiness to make these links seems to have diminished, as has our patience with collecting rare things.

For example, at the moment it is entirely possible to put together a complete collec- tion of Milton first editions on a reasonably modest budget, but it would nonetheless take a little time while you waited for some of the books to come on to the market. That wait, that anticipation, is of course one of the things that separates collecting from shopping, but the British seem, un- iquely, to have lost the appetite. It is extraordinary that we make such a regular rumpus about losing abroad our visual heritage — often objects which were fashioned in other countries — when we take so little interest in our own literary forebears with whom we have far stronger links. It is also not a little shaming.

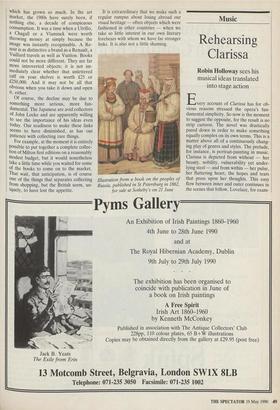

Illustration from a book on the peoples of Russia, published in St Petersburg in 1862, for sale at Sotheby's on 21 June

Previous page

Previous page