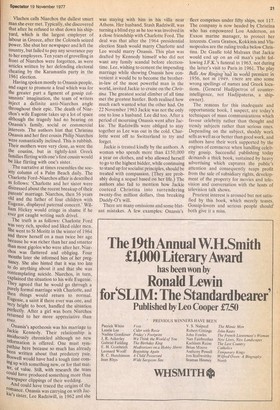

Social climber meets hustler

Taki Theodoracopubs

Aristotle Onassis Nicholas Fraser, Philip Jacobson, Mark Ottaway and Lewis Chester (Weidenfeld and Nicolson £6.50) The dust-cover of the Sunday Times former Insight Team's latest contribution to con temporary history informs us that the biography of Onassis, 'the beguiling and likeable scoundrel with extraordinary talents,' is the result of intensive research all over the world by the four co-authors.

In America, where things like this are not unusual, the authors would probably be sued for false advertising since rarely has a book shown less insight, research and 'wealth of new information'. What it con tains is a regurgitation of old, sometimes apocryphal yarns, vignettes lifted from the books listed in the bibliography, and long quotations from government and maritime commission records in Europe, the United States and South America.

I do not mean to convey the impression that the subject deserved a more serious study by a more serious group of writers.

What I find hard to understand is why four journalists have spent as much money, mobilised as many people — fifty-five main contributors plus the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the State Department and the CIA — in order to write a superficial book of a tycoon's thirst for acquisition, a thirst so common among altruistic and literate people such as Adnan Kashoggi and Jackie Kennedy Onassis.

Despite using every trick to show insight and knowledge of the subject, the authors do not live up to the team's name. A great deal of the book repeats what Willi Frischauer wrote in his 1968 hagiography. The rest is divided among Ingeborg Dedichen's opportunistic revelations of 1975, newspaper reports, gossip columnist stuff and information handed out by Onassis's public relations hacks. The strongest sections of the book are the parts dealing with the bus iness side of his life: the various transactions, his ingenious ways of financing ships, his troubles with the American government and his efforts to corner the market in the Saudi Arabian deal. These are well reported because they are based on government records and they were well explained to the team by Costa Gratsos, a loyal friend and right-hand man of Onassis. Gratsos is an astute businessman, has a lot of charm and is a gentleman. His contribution manages to veer the narrative off the gossip-column staccato rhythm, although his views are subjective, to say the least.

The book traces Onassis from womb to tomb. Middle-class upbringing in Asia Minor, the sacking of Smyrna by the victorious Turkish armies, his flight to Greece and the Argentine, are all reported according to the version put out by Onassis once he became rich and famous. The initial successful business ventures selling Greek tobacco in the Argentine, the acquisition of his first ship, his shrewdness, hustle and cutting of corners, as well as his constant thirst for money and power are chronicled in detail and explained in one sentence: 'An overwhelming desire to impress his father from whom he felt rejected.' What insight. Harold Robbins could not have done better. If the Insight Team had taken a bit more time to read history instead of gossip columns they would have concluded what most Greeks agree upon today: that 500 years of Turkish occupation and foreign interference have made Greeks distrust the state, rely only on themselves, and believe in the only commodity that ensures freedom from the state, money. Having lived under the Turkish yoke is a better explanation of Onassis's passion for power rather than the Hollywood solution of paternal misunderstanding.

Intimate flashes of Onassis and his propensity for 'practical' jokes are illustrated in an effort to show mastery of the subject. An example: Onassis asks Inge Dedichen to inspect his backside as he fears he is suffering from piles. 'When she solicitously complied she was rewarded with a fart in the face.' The authors attribute more space to such windy subjects than the tycoon's strange cynicism and total lack of ideology. The latter takes up two sentences: 'He displayed no interest, commercial or political in the Spanish Civil War. . 2 and, 'while the Battle of Britain was in progress, he sailed from London bound for New York.'

An almost total ignorance of the Greek shipping community in New York at the time is displayed when the authors describe Niarchos and Onassis as parvenus trying to crash the community in 1945. Although I am sticking my neck out this information smells as if it came from Emmanuel Kulukundis, once a New York shipowner of note, later bankrupt and offering more sour grapes than real information. Greeks, especially shipowners, do social climb, but, heaven forbid, never with other Greeks, only with hoi polloi of the country they find themselves in. The shipping community, especially the New York one, embraces every shipowner — large or small — and ninety per cent of the ones included pretend they are not.

Throughout the book the reader can almost feel the team's efforts to stay away from touchy or libellous subjects. They throw caution to the wind, however, when the parties involved are dead. For example, they state with unusual authority that Onassis and Evita Peron (Argentina's first lady at the time) made love in Portofino in the summer of 1947. Gianni Agnelli, the chairman of FIAT, was a lifelong friend of both Evita and Onassis. He was in Portofino that summer and remembers her visit. She had come to Europe on an unofficial trip, supposedly for a holiday. The real reasons which were kept secret were that she already had begun to suffer from the cancer that finally killed her five years later. Agnelli told me that 'nothing could have been further from her mind than sleeping with the charming but greasy Greek.' Stories like that were part of the legend invented by Onassis, repeated by his entourage and reported by the authors.

Onassis's rivalry with Stavros Niarchos is greatly exaggerated and reported from sources close to the former. (Robert Maheu, who worked for Niarchos on a single project, is the only person used as a source by the team who was not on Onassis's payroll.) The Niarchos-Onassis involvement in Greek industry, and the efforts by the military government, as well as the one of Constantine Karamanits before the Colonels, to entice foreign Greeks to invest in the mother country are presented as a result of one-upmanship bY the two tycoons. This is not true and a copout by the writers. Both Niarchos and Onassis drove hard bargains with the Greek government — and the Greek state bent over backwards to accommodate them — because of past history.

Millions of Greeks have emigrated in the last 150 years in search of a better life. Many of them have returned to Greece with their savings and invested them in businesses. Too many of them have seen their investments wiped out by retroactive laws imposed when opposition parties were voted into office. There have been thirtYtwo coups since 1830 in Greece — many of them arranged by politicians coming Of second best at the polls — and about half 85 many different constitutions. In order t° attract investment, therefore, governments have to offer good deals to entrepreneurs. The authors quote Helen Vlachos, a newspaper publisher, on this subject. She, claims that the Colonels 'sold' half 0.1 Greece away to enterprising businessmen during their seven-year dictatorship. She accuses Niarchos and Onassis of having taken advantage of this sale. This is a fundsmental misrepresentation; the authors nevertheless quote it without comment. I° reality, Helen Vlachos was not only insult' mental in Niarchos and Onassis receiving the lion's share of Greek investment, but actually defended all concessions going t° the two tycoons in print, because both Nilarchos and Onassis did their business before the Colonels came to power. And Held Vlachos applauded them in printwhile receiving their hospitality for the better par'. of ten years. • Vlachos calls Niarchos the dullest smart man she ever met. Typically, she discovered that after he refused to shut down his shipyard, which is the largest employer of labour in Greece, after the Colonels seized power. She shut her newspaper and left the country, but failed to pay any severance pay to her employees. Ten years of grovelling in front of Niarchos were forgotten, as were articles written by her defending electoral cheating by the Karamanlis party in the 1961 election.

Having spoken mostly to Onassis people, and eager to promote a feud which was for the greater part a figment of gossip columnists' imagination, the team of writers inject a definite anti-Niarchos angle throughout their epic. The death of Niarchos's wife Eugenie takes up a lot of space although the tragedy had no bearing on Onassis's family, social or commercial interests. The authors hint that Christina Onassis and her first cousin Philip Niarchos were romantically inclined. This is rubbish. Their mothers were very close, as were the the cousins, but in tightly-knit Greek families flirting with one's first cousin would be like flirting with one's sister.

The narrative at times resembles the society column of a Palm Beach daily. The Charlotte Ford—Niarchos affair is described as follows: 'Charlotte and her sister were distressed about the recent breakup of their Parents' marriage. Niarchos, then 56 years Old and the father of four children with Eugenie, displayed paternal concern.' William Hickey would cringe in shame if he ever got caught writing such drivel.

The truth is as follows: Charlotte Ford was very rich, spoiled and liked older men. She went to St Moritz in the winter of 1964 and threw herself on a man twice her age because he was richer than her and smarter than most gigolos who were after her. Niarellos was flattered and obliging. Four months later she informed him of her pregnanq. She also hinted that it was too late to do anything about it and that she was Contemplating suicide. Niarchos, in turn, explained the situation to his wife Eugenie. They agreed that he would go through a Purely formal marriage with Charlotte, and then things would return to normal. EUgenie, a saint if there ever was one, and very bright to boot, handled the situation Perfectly. After a girl was born Niarchos returned to her more appreciative than ever.

Onassis's apotheosis was his marriage to Jackie Kennedy. Their relationship is a. ssiduously chronicled although no new Information is offered. One must sympathise here because so much has already teen written about that predatory pair, oswell would have had a tough time coming up with something new, or for that matter, of value. Still, with research the team Could have produced something more than newspaper clippings of their wedding. And could have traced the origins of the romance. Onassis was carrying on with Jackie's sister, Lee Radziwill, in 1962 and she was staying with him in his villa near Athens. Her husband, Stash Radziwill, was turning a blind eye as he too was involved in a close friendship with Charlotte Ford. The deal was that after the 1964 presidential election Stash would marry Charlotte and Lee would marry Onassis. This plan was drafted by Kennedy himself who did not want any family scandal before electiontime. Lee, wishing to cement the impending marriage while showing Onassis how convenient it would be to become the brotherin-law of the most powerful man in the world, invited Jackie to cruise on the Christina. The greatest social climber of all time met the greatest hustler. Both realised how much each wanted what the other had. On 22 November 1963 Jackie was not the only one to lose a husband. Lee did too. After a period of mourning Onassis went after Jackie. The Radziwills were obliged to stay together as Lee was out in the cold. Charlotte went off to Switzerland to try and forget.

Jackie is treated kindly by the authors. A woman who spends more than £150,000 a year on clothes, and who allowed herself to go to the highest bidder, while continuing to stand up for socialist principles, should be treated with compassion. (They are prob ably doing a sequel based on her life.) The authors also fail to mention how Jackie coerced Christina into surrendering twenty-five million dollars, thus breaking Daddy-0's will.

There are many omissions and some blatant mistakes. A few, examples: Onassis's fleet comprises under fifty ships, not 117. The company is now headed by Christina who has empowered Lou Anderson, an Exxon marine manager, to protect her interests. Costa Gratsos, Kokkinis and Vlassopoulos are the ruling troika below Christina. De Gaulle told Malraux that Jackie would end up on an oil man's yacht following J.F.K.'s funeral in 1963, not during the latter's visit to Paris in 1961. The play Bells Are fiing.ing.hadits world premiere in 1956, not in 1949. 1 here are also some wrong spellings of names and Greek locations. (General Hadjipetros of counterintelligence, not Hadjipateras, a shipowner).

The reasons for this inadequate and opportunistic book, I suspect, are today's techniques of mass communications which favour celebrity rather than thought and trendy subjects rather than serious ones. Depending on the subject, shoddy work sells as well as or better than good work, and authors have their work supported by the engines of commerce when handling celebrity gossip. Successful publishing today demands a thick book, sustained by heavy advertising which captures the public's attention and consequently reaps profit from the sale of subsidiary rights, development of the property for movies and tele-. vision and conversation with the hosts of television talk shows.

Prurient interest is aroused but not satisfied by this book, which merely teases Gossip-lovers and serious people should both give it a miss.

Previous page

Previous page