WHY SICILY NEEDS ITS LEOPARD

Simon Blow meets

the survivors of the Sicilian aristocracy

WHAT has happened to Sicily's aristocra- cy since Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa wrote his famous novel The Leopard? It was a book that, for the first time, brought worldwide attention to a neglected island nobility, though at the end of the book there appeared to be little hope that an aristocratic ruling class could long continue to hold its own in Sicily. Lampedusa was chiming their funeral bells as far back as 1910 (the book's closing section) and now it is exactly 30 years since his remarkable best-seller was published. But the Sicilian nobility — who are still very much there did not take kindly to the book when it came out. There were complaints that it was a novel full of 'gossip' — a charge frequently levelled at books that hit too hard at the truth — and they did not like the exposure. How, for instance, could he have mentioned a prince who keeps a low- class mistress in Palermo or have suggested that their day was on the wane? But Lampedusa, of course, was deaf to their complaints; he had died in 1957 at the age of 60, believing that his book was too old-fashioned to find a publisher.

Yet Lampedusa was right. The power and the pomp did fall from the Sicilian aristocracy with the departure of the Bour- bon monarchs, though it was not a matter that the nobility liked to study too atten- tively. Gone were the secure old days when an enlightened Prince of Biscari could afford to feed the whole population of Catania, and going rapidly was their poli- tical and economic prestige. By the 1860s a middle class was rising — growing richer as the nobility grew poorer — but for the Sicilians the first crunch had already come in 1812 when primogeniture was abolished and the entail of estates broken. Such liberal moves occurred chiefly through the clumsiness of Bourbon rule, which brought frequent revolts and cries for reform. But a rational approach to politics is alien in a country where factions and jealousies rise as easily as spring water; invariably reform led only to further confusion and unrest. The well-known Sicilian economist, Balsa- mo, commented 200 years ago, 'Too much liberty is for the Sicilians what would be a pistol or a stiletto in the hands of a madman.'

And the aristocracy did not like Lampe- dusa's implication that they could not manage their estates. The Prince, Don Fabrizio, makes no effort to modernise his farming, or augment his income, and he allows himself to be cheated to right and left. Yet one of the reasons for Sicily's backwardness was the aristocracy's refusal to be business-like or progressive on their estates. They preferred to build palaces that often they could not afford to finish, or to compete with each other over the grandeur of their carriages and the number of horses that drew them. They had no desire to involve themselves in the doings of the world. But this turning of the back is true of Sicily as a whole. When Garibaldi landed with his thousand, few Sicilians had any idea of what he was about. Many thought the yells of 'Italia!' Italiar must be a reference to his girlfriend, and they were bamboozled into voting for the unification in the belief that they were simply voting their appreciation of Garibaldi. It is that great solitary figure Don Fabrizio — the Leopard himself — who becomes Lampedusa's spokesman for the Sicilian character. When the Prince ex- plains to the northern aristocrat, Chevalley di Monterzuolo, why he has no wish to accept the northerner's invitation to join the new Senate of the new united Italy, we are made to realise what has truly hap- pened to this vulnerable island. His poised and polished speech should be obligatory reading for all who want to understand Sicily, then and now. 'We are old, Cheval- ley, very old,' the Prince begins.

For over twenty-five centuries we've been bearing the weight of superb and heter- ogeneous civilisations, all from outside, none made by ourselves, none that we could call our own. We're as white as you are, Cheval- ley, and as the Queen of England; and yet for two thousand five hundred years we've been a colony. I don't say that in complaint; it's our fault. But even so we're worn out and exhausted . . . Sleep, my dear Chevalley, sleep, that is what Sicilians want, and they will always hate anyone who tries to wake them, even in order to bring them the most wonderful of gifts . . . All Sicilian self- expression, even the most violent, is really wish-fulfilment; our sensuality is a hankering for oblivion, our shooting and knifing a hankering for death; our languor, our exotic ices, a hankering for voluptuous immobility, that is for death again; our meditative air is that of a void wanting to scrutinise the enigmas of Nirvana.

Most visitors to Sicily, and in particular those from northern countries and the north of Italy, quite fail to appreciate these aspects of the Sicilian. Visitors cannot reconcile themselves to the Sicilian's proud indifference to the northern ethic of 'get- ting things done'. Living here for a few months, I frequently meet north Italians, and their grudge against Sicilians always takes the same form: 'But the Sicilians are so lazy. If they have an earthquake they wait for somebody else to build their houses. But when we had our earthquake at Trieste everything was rebuilt in six months.'

I reply that as no Sicilian has ever been allowed to take his country in hand, how can they expect this response? But neither can they conceive the immense self-respect the Sicilian has acquired over the centuries of his defeat. 'We are gods,' Don Fabrizio `Vegetarian!' tells the Englishman, and no wonders from the outside world will ever impress a Sicilian.

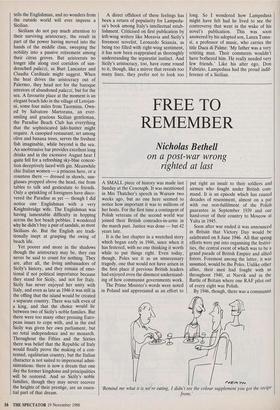

Sicilians do not pay much attention to their surviving aristocracy, the result in part of the power having moved into the hands of the middle class, sweeping the nobility into a passive retirement among their citrus groves. But aristocrats no longer idle along cool corridors of sun- drenched palazzi, as Burt Lancaster and Claudia Cardinale might suggest. When the heat drives the aristocracy out of Palermo, they head not for the baroque interiors of abandoned palazzi, but for the sea. A favourite place at the moment is an elegant beach lido in the village of Letojan- ni, some four miles from Taormina. Own- ed by Salvatore Martorana, an ever- smiling and gracious Sicilian gentleman, the Paradise Beach Club has everything that the sophisticated lido-hunter might require. A canopied restaurant, set among olive and banana trees, serves the freshest fish imaginable, while beyond is the sea. An unobtrusive bar provides excellent long drinks and in the excessive August heat I quite fell for a refreshing sky-blue concoc- tion deceptively laced with gin. Meanwhile chic Italian women — a princess here, or a countess there — dressed in shawls, sun- glasses propped above the head, rise from tables to talk and gesticulate to friends. Only a sprinkling of foreigners have disco- vered the Paradise as yet — though I did notice one ' Englishman with a very Knightsbridge wife. The Englishman was having lamentable difficulty in hopping across the hot beach pebbles. I wondered why he didn't buy a pair of sandals, as most Sicilians do. But the English are tradi- tionally inept at grasping the swing of beach life.

Yet poorer and more in the shadows though the aristocracy may be, they can never be said to count for nothing. They are, after all, the living ambassadors of Sicily's history, and they remain of emo- tional if not political importance because they stand for Sicily, and not for Italy. Sicily has never enjoyed her unity with Italy, and even as late as 1946 it was still in the offing that the island would be created a separate country. There was talk even of a king, and that the choice would lie between two of Sicily's noble families. But there were too many other pressing Euro- pean issues to cope with, and in the end Sicily was given her own parliament, but no total independence and no monarch. Throughout the Fifties and the Sixties there was belief that the Republic of Italy would finally prove the making of a con- tented, egalitarian country, but the Italian character is not suited to impersonal admi- nistrations: there is now a dream that one day the former kingdoms and principalities will be restored. And so Sicily's noble families, though they may never recover the heights of their prestige, are an essen- tial part of that dream. A direct offshoot of these feelings has been a return of popularity for Lampedu- sa's book among Italy's intellectual estab- lishment. Criticised on first publication by left-wing writers like Moravia and Sicily's foremost novelist, Leonardo Sciascia, as being too filled with right-wing sentiment, it has now been reappraised as thoroughly understanding the separatist instinct. And Sicily's aristocracy, too, have come round to it, though, like a mirror that reveals too many lines, they prefer not to look too long. So I wondered how Lampedusa might have felt had he lived to see the controversy that went in the wake of his novel's publication. This was soon answered by his adopted son, Lanza Toma- si, a professor of music, who carries the title Duca di Palme: 'My father was a very retiring man. Their comments wouldn't have bothered him. He really needed very few friends.' Like his alter ego, Don Fabrizio, Lampedusa had the proud indif- ference of a Sicilian.

Previous page

Previous page