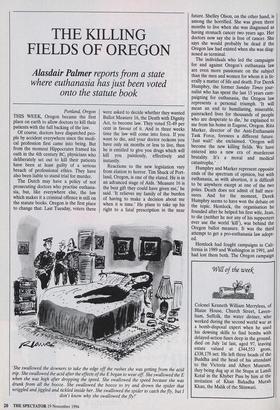

THE KILLING FIELDS OF OREGON

Alasdair Palmer reports from a state where euthanasia has just been voted onto the statute book Portland, Oregon THIS WEEK, Oregon became the first place on earth to allow doctors to kill their patients with the full backing of the law.

Of course, doctors have dispatched peo- ple by accident everywhere since the medi- cal profession first came into being. But from the moment Hippocrates framed his oath in the 4th century BC, physicians who deliberately set out to kill their patients have been at least guilty of a serious breach of professional ethics. They have also been liable to stand trial for murder.

The Dutch may have a policy of not prosecuting doctors who practise euthana- sia, but, like everywhere else, the law which makes it a criminal offence is still on the statute books. Oregon is the first place to change that. Last Tuesday, voters there were asked to decide whether they wanted Ballot Measure 16, the Death with Dignity Act, to become law. They voted 51-49 per cent in favour of it. And in three weeks time the law will come into force. If you want to die, and your doctor reckons you have only six months or less to live, then he is entitled to give you drugs which will kill you painlessly, effectively and instantly.

Reactions to the new legislation vary from elation to horror. Tim Shuck of Port- land, Oregon, is one of the elated. He is in an advanced stage of Aids. 'Measure 16 is the best gift they could have given me,' he said. 'It relieves my family of the burden of having to make a decision about me when it is time.' He plans to take up his right to a fatal prescription in the near

'She swallowed the downers to take the edge off the rushes she was getting from the acid trip. She swallowed the acid after the effects of the E began to wear off. She swallowed the E when she was high after dropping the speed. She swallowed the speed because she was drunk from all the booze. She swallowed the booze to try and drown the spider that wriggled and jiggled and tickled inside her. She swallowed the spider to catch the fly, but I don't know why she swallowed the fly!'

future. Shelley Olson, on the other hand, is among the horrified. She was given three months to live when she was diagnosed as having stomach cancer two years ago. Her doctors now say she is free of cancer. She says she would probably be dead if the Oregon law had existed when she was diag- nosed as terminal.

The individuals who led the campaigns for and against Oregon's euthanasia law are even more passionate on the subject than the men and women for whom it is lit- erally a matter of life and death. For Derek Humphry, the former Sunday Times jour- nalist who has spent the last 15 years cam- paigning for euthanasia, the Oregon law represents a personal triumph. 'It will mean an end to humiliating, miserable, painracked lives for thousands of people who are desperate to die,' he explained to me from his home in Eugene, Oregon, Rita Marker, director of the Anti-Euthanasia Task Force, foresees a different future. `Just wait!' she exclaimed. 'Oregon will become the new killing fields. We have entered into a new era of murderous brutality. It's a moral and medical catastrophe.'

Humphry and Marker represent opposite ends of the spectrum of opinion, but with euthanasia, as with abortion, it is difficult to be anywhere except at one of the two poles. Death does not admit of half mea- sures. And for the moment, Derek Humphry seems to have won the debate on the topic. Hemlock, the organisation he founded after he helped his first wife, Jean, to die (neither he nor any of his supporters ever use the world was behind the Oregon ballot measure. It was the third attempt to get a pro-euthanasia law adopt- ed.

Hemlock had fought campaigns in Cali- fornia in 1989 and Washington in 1991, and had lost them both. The Oregon campaign

was as vicious as ever, each side accusing the other of deliberately misleading the public.

Hemlock's commercials featured a woman named Patty Rosen who said she had given her daughter poison pills to spare her the pain of incurable cancer. 'In the 1989 California campaign, the same woman said she gave her daughter a lethal injection,' an irate Rita Marker claimed. `How could she lie about something as critical as that?' Derek Humphry, on the other hand, says the opposition's invoca- tion of the spectre of the killing fields, with him as the Pol Pot of euthanasia, was `infantile scaremongering'.

The demonising tactics backfired. Enough people felt they might want to take advantage of euthanasia to ensure that the attempt to portray its practitioners as the vanguard of a Nazi-style extermina- tion campaign failed. Voters are also disil- lusioned with doctors who make fortunes by prolonging dying patients' lives as long as possible. The vehement opposition of the American Medical Association to the Death with Dignity Act probably helped it to pass.

`We'd educated the public and smashed the taboo,' a disconcertingly cheerful Humphry told me. Humphry's own book, Final Exit, played a critical role in that pro- cess- it analyses various methods of suicide comparing hanging, shooting, drowning, poisoning, burning, suffocation (car exhausts versus gas ovens), freezing (described as 'a method for which I have respect, it takes a certain sort of person to wish to freeze to death on a mountain') and electrocution — before finally coming down on the side of poisoning. The book gives instructions on how to prepare, and where to purchase, drugs that ensure death quickly and without pain.

Final Exit was one of America's best- selling books in 1991, and three years on it still sells well. 'It answers a need,' Humphry says. 'People want to be able to choose when they die. They do not want doctors to take that decision for them. Medical care for terminally ill people can be painful and humiliating, as well as ruinously expensive. Final Exit represents a sort of insurance policy.'

But DIY suicide never works as reliably and effectively as the doctor-aided variety, which is one reason why Humphry lobbied for legislation. 'But I also wanted the law to recognise one of the most fundamental of all human rights: the right to die with dignity. When you have seen people who so want to die that doctors have tied their hands to their bed in order to prevent them from pulling the drips that feed them out of their veins, you have to recognise that the crime isn't helping them to die when that's all they want, it's forcing them to live.' The simplicity of Humphry's message has been extremely persuasive. All he says he is doing is advocating choice: he wants the law to extend people's control of their own lives by allowing them to control their own deaths.

The argument is hard to counter directly, except from the explicitly religious premise that each life belongs not to the person who lives it but to God, and only He has the right to take it away. Religious funda- mentalism of that kind has not been effec- tive in a culture which cherishes individual liberty above all other values. The oppo- nents of euthanasia recognise that. Though the opposition to the Death with Dignity Act was mostly funded by the Catholic Church, Humphry's adversaries did not campaign by claiming that euthanasia vio- lated God's laws.

Rita Marker, a professor of political sci- ence and ethics at Steubenville University in Illinois, is a very sophisticated lobbyist. She's a Catholic, but she is adamant that `euthanasia is not a religious issue. It's an issue about public policy. Do you think the solution to suffering is to kill the sufferer? If you do, you'll join Humphry's organisa- tion.' She is also a violent polemicist, She has said of Dr Jack Kevorkian, the self-pro- claimed suicide specialist whose personally designed suicide machine has helped dis- patch more than ten terminally ill patients, that lad he been born fifty years earlier, he probably would be designing gas ovens rather than medical equipment'.

She told me she thought Humphry 'a liar and a charlatan, a cold and heartless man who killed his first wife and his father in law, then drove his second wife to suicide'. She has even written a book — Deadly Compassion: The Death of Ann Humph?), (the second Mrs Derek Humphry) and The Truth About Euthanasia — which claims to prove those charges, although Humphry himself is utterly unfazed by Marker's tome, which he says has 'failed to sell'.

But beneath the abuse Professor Marker articulates a concern which worries many of euthanasia's supporters: in a society where medical care is ruinously expensive, the availability of death on demand is bound to lead to some people feeling pres- sured to take up the option when it's not actually what they want. The Death with Dignity Act has the potential to become a greedy relative's charter, with children hovering over their parents, desperate to persuade them to take the quick way out before their inheritance disappears in medical fees.

What you'll find,' warns Professor Mark- er, 'is that it is overwhelmingly the poorer, less well-off people who'll choose death. Death's the ultimate in cost-containment. Rich people will ensure they get treated with everything possible until the very end. It's the poor, who know that their treat- ment is mortgaging their children's future, who will ask for the fatal prescription.'

Professor Marker, following the bulk of the American medical profession, is also concerned that the safeguards built into the Act may be seriously inadequate. The diagnosis needs to be that you have six months to live, but, in Oregon, one doc- tor's opinion on that notoriously difficult question will be enough. A second doctor will have to verify that you have made the request, and that you were not clinically depressed when you made it; you will then have to wait a further two weeks before your doctor is legally allowed to give you the poison. But will that be enough time to detect bullying or coercion? Or to catch unscrupulous doctors who have been bribed or bullied themselves by unscrupu- lous relatives into making the required 'six months to live' diagnosis?

Derek Humphry brushes aside those concerns with a contemptuous shrug. `Look,' he snorts, 'there are bound to be a number of abuses. There are with any law. But the existence of theft is not a reason for the abolition of private property.' What about subtle social or familial pres- sures on older people to get out of the way? 'I don't think that's going to be a problem. The will to live is far too strong in most people. They'll only choose to die if that's what they really want.'

Humphry's unshakable confidence is disconcerting because it seems to indicate an inability to perceive what is a real prob- lem: the old, the frail and the terminally ill can obviously be bullied into decisions which they do not want to take. What the availability of legal euthanasia will do to family relations in Oregon is not difficult to predict. If euthanasia were available here, and your mother was a candidate, how could you convince her that you did not want her to sign up? Oregon's electorate voted for the Death with Dignity Act because they were more frightened of being bullied by doctors into living than they were of being bullied by their families into dying. The medical pro- fession's ability to keep people alive has now so far outstripped its capacity to cure them that the fear of becoming a living corpse hooked up to a life-support system now outweighs almost everything else, including death.

Until medicine finds a way to close that gap between keeping alive and curing, the pressure for some form of legalised euthanasia will increase. Derek Humphry is convinced that Oregon's law is the harbinger of things to come. He predicts that in the next ten years most states will pass similar measures. 'But it probably won't happen in Britain,' he sighs, 'because Britain is such an undemocratic country that the government can go on ignoring the wishes of the people indefinitely.'

Alasdair Palmer is home affairs editor of The Spectator.

Previous page

Previous page