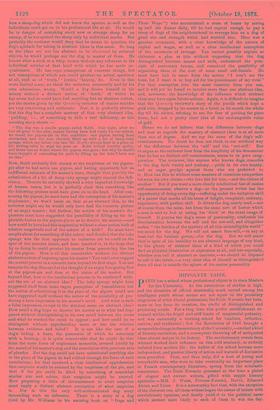

HIPPOLYTE TAINE.

PARIS has a school whose professional object is to train Masters for the University. As the curriculum of studies is high, and the situation of official mastership much envied among the intelligent youth whose means are not equal to the pecuniary exigencies of other liberal professions, the Boole Normale has been, more or less from its creation, the cradle of distinguished and promising minds. For a long time this public establishment re- mained within the frigid and stiff limits of magisterial pedantry, and was essentially a training-school for teachers, orthodox, narrow, and traditional ; but the Revolution of 1848 brought a memorable change in the sanctuary of the University,excited akind of literary emulation, and a consequent throwing off of antiquated ideas almost unique in its history. The revolutionary events from without worked their influence on this cold seminary, so entirely isolated from modern life: the habits of the school became more independent, and greater liberty of action and warmth of discussion soon prevailed. Then, and then only, did a host of young and remarkable men, who were to take eventually an important place in French contemporary literature, spring from the scholastic renaissance. The Ecole Normale possessed at the time a pleiad of elegant and correct writers, gifted with supple literary aptitudes,—MM. J. Weiss, Prevost-Paradol, Herve, Edmond About, and Tame. It is a noteworthy fact that, with the exception of the cleverest one, all these writers began the career of letters with revolutionary opinions, and finally yield 3d to the political cause 'which seemed most likely to each of them to win the day.

Our business is with M. Taine, who alone has remained what he was formerly, and is more particularly known in England as one of the few Frenchmen who have devoted thoughtful study to a country whose customs and characteristics are but too little known over the Channel. He is undoubtedly the most independent of noted" Nor- maliens," for although M. Edmond About has often trodden under foot his doctoral gear to assume the fool's cap, he never dared to break so openly as M. Taine with the prejudices and tradi- tions of the French University. From the beginning, the historian of English literature despised orthodoxy, and determined, to use 13alzac's picturesque expression, "to throw the house out by the -window." Trained and accustomed to respect for masters, lobe of antiquated methods, submission to authority, his first writings breathed in every line the purpose of inno- vating ; and in fact, he has created a complete philo- sophical system, owing more to physiology than psychology ; and which has, at least, the attraction of eminent originality. In order to clear the ground covered with the debris of anterior philosophies, XL Taine proceeded to demolish, or appear to demolish, with marvellous verve, and a subtlety that left far behind the most perfidious sophistry, all the theories of the French ideologists of the age,—Royer-Collard, Laromi- guiere, Cousin, Jouffroy, and others, denying the body and 'details of their spiritualistic theories, and finally rehabilitating anew those doctrines of Condillac which attribute to ideas no other origin than the perceptions of the senses ; for although M. Taine has frequent recourse to Locke and Hegel, he 'distinctly bases himself on the theories of the author of the "Treatise on Sensations." This tardy and audacious affirmation -of materialism was a thunder-stroke for the Sorbonne, for the Attack was clearly enunciated, precise, well directed, and fear- lessly expounded in book, review, and journal. M. Taine was still, at that time, professor of the University, but a year of tuition was too much for him ; he threw up the appoint- ment, devoted himself to letters, and was immediately admitted to the staff of the Journal des Debats and Revue des Deux Mondes, where he brusquely developed his new theory of national and individual 'character and literature. After showing that in intellectual embryo- logy (to quote his own expression) all the intellectual and physical powers of man are grouped around a predominating faculty, and -so completely subjected to its influence that they become, as it were, its slaves, M. Taine sought the birth and origin of this predominating faculty ; and this gave rise to his ingenious system of geographical and atmospheric influence on the human frame, as also that of moral resultants, in which he explains the birth, special aptitudes, and diversity of artistic and literary tempers, by the influences of _races, society, education, organisation, passions, manners, incidents of life, of all, in short, that touches man and modifies him in his physical and psychological nature. In the latter sense, M. Thine goes even further, for according to his system, the soul perforce disappears. This is in no way an exaggeration, for M. Taine himself has written that "the productions of the human mind as well as those of organic life are only to be explained by the atmosphere in which they thrive ;" and he expounds his theory still more plainly in his fine "Voyage aux Eaux des Pyreedes," when, -speaking of the Beam peasants, he says :—" Here, men are thin -and pale ; their bones protrude, and their features are large and severe, like their mountains. An eternal struggle with the soil has made women stunted as well as plants ; it has left in their eyes A vague expression of melancholy and reflection The impressions of the soul and the body modify in the long run the body and the soul ; the race moulds the individual, and the country moulds the race. A degree of heat in the atmosphere and of inclination in the soil is the primary cause of our faculties and passions." It is not difficult to see the space left to the soul in such a system, and it is all but certain that this materialist display, so brilliant and so novel that philosophers and lettres were as much -astonished as shocked at its exhibition, would have excited protestations from even the scientific, if the innovator had not taken good care to clothe his matter in a wonderful display of glittering draperies of light and harmony, and used all the fertile resources of his imagination ; for the scientific and medical -studies by which M. Taine prepared himself for three consecutive Tears before taking the field had not impaired the light and bril- liant varnish which fascinates men just as a mirror dazzles larks. Essentially French in temper, and supremely gifted with the irresistible and deceptive charms of wit, M. Taine was certain of the approbation of his public—whether in writing or speech—for the enunciation of the weirdest and most bizarre ideas, for he was lucky enough to be magister elegantiarum in a country where more attention is accorded to the manner of saying things than to the things that are said.

When he was appointed to the Professorship of lEsthetics at the School of Fine Arts in Paris, he applied himself from the very first to demonstrate to his pupils that aesthetics did not exist. Thus he once made to his auditors this singular confession, "Modern and ancient msthetics differ in this sense, that the one is historical and the other dogmatical ; modern Eesthetics do not impose precepts, but recognise new laws. Besides, I cannot help thinking, from the bottom of my conscience, that only two precepts have ever been discovered ; the first is to be born with genius,—that is the business of your parents, not my business ; the second consists in studying a great deal, so as to possess your art thoroughly,—that is your business, not mine." The auditory in whose hearing M. Taine exposed his sesthetical theories was not only composed of pupils of the School of Fine Arts, but the world of fashion, and the elegant as well as the gravest men, all those who like to hear fine periods and musical phrases, attended his courses every Thursday, and on that day the lecture-room of the Rue Bonaparte bore much resemblance to the interior of a theatre or concert-hall ; fine toilettes and rich costumes swept over the dusty boards, and beside the harmonious images, sonorous antitheses, and luminous metaphors that fell from the professor's lips, the scintillation of diamonds and the elite of the dazzling Parisian beauty might have borne com- parison with those of the most brilliant nights of Ventadour. From this time, what is called in Paris "Le Monde" adopted M. Taine, as it adopts everything that enchants and pleases it. The ancient " Normalien " had found the secret of captivating. M. Taine has, in truth, the finest command of language, the most striking vocabulary, the most cleverly undulating and serpentine phrases, that a mundane orator could well wish for. The bold para- doxes and rash propositions frequently put forth in his lectures would be refuted, were they presented by others with less art, while they contribute to show off the supple and energetic qualities of his talent. This suppleness is evident enough in his "history of Eng- lish Literature," which ought to be called, said Sainte-Beuve, The History of the English Race and Civilisation through its Litera- ture.'" Neither was this facility restricted to serious works; in 1866 and 1867, the gourmets of Parisian literature were greatly surprised at the appearance in the pages of the Vie Parisienne of a series of

articles on elegant Paris, uniting the penetrating faculty of observa- tion which savoured of Stendhal and Balzic with that richness of style which belongs to Theophile Gautier alone. These articles were signed by a certain Frederic Thomas Graindorge, who ap- pended to his name the singular qualifications of "Doctor of philosophy of the University of Jena, senior partner of the firm Graindorge and Co. (oils and salt pork, at Cincinnati, United States)." The author reviewed the manners, tastes, fantasies, caprices, and eccentricities of the French aristocracy with extraordinary wit, vivacity, and lightness of style. One day, Paris learned that the Thomas Graindorge was no other than the amiable professor of teathetios of the School of Fine Arts, and that M. Taine, by way of reposing himself after serious work, indulged in these clever delineations. M. Taine was then accepted by the most Parisian of Parisians, as the most lettered of the lettered had accepted him, as an equal ; he had no longer reason to fear the enmities which an im- placable and fearless avowal of materialist theories would have been sure to raise in his path. M. Taine proved himself a wise politician in thus parading his Parisian and worldly powers, for in the last years of the Empire the Ultramontane party directed their full wrath against what they styled "the clan of Freethinkers," which was composed of the most illustrious persons of the day, and the reputation of worldly wit was his best protection.

M. Taine is now in the full vigour of age and talent ; and any slight harshness of style, such as was noticeable in his first years of literary renown, has completely disappeared. The sharp angles have been softened ; his exuberant colour of style has become more harmonious, and his mental gifts form a homogeneous whole. Soft in manners, free from the heavy and antipathetic coldness of tradition-worshippers, he has successfully attained the first rank, and gently insinuated himself into minds and hearts. If he were judged by his own theory of literary genius, he could not be distinctly styled an historian, a poet, or an orator. His personality has a little of all three ; and the qualifi- cation of " charmer " is the only one that seems adapted to his

Previous page

Previous page