Will a lion come?'

Memories of Evelyn Waugh

Richard Acton

My parents, John and Daphne Acton, were friends of Evelyn Waugh from 1936 until the writer's death 30 years later. I knew nothing of him in the earlier years (I was born in 1941), but after the second world war our vast family emigrated from England to Southern Rhodesia, today's Zimbabwe, and in 1958 and 1959 Waugh paid us two memorable visits. The follow- ing year I stayed with him in Somerset.

Waugh in middle age has been portrayed as jaded, but the Waugh we saw in Rhode- sia was usually amused and always stimu- lating. At times, certainly, he was bored, but for the most part he was in good spirits. Not only did he make us laugh, but he laughed himself a great deal.

In 1936 Waugh was 32, and famous. He had marooned himself in Shropshire to work on a travel book, Waugh in Abyssinia. My parents then lived in Shropshire at Aldenham Park. My father's sister, Mia Woodruff, brought the writer over that April, and Waugh wrote to my mother: 'I absolutely loved my visit.' Soon after that, Waugh came for another weekend. On the Sunday afternoon, my father proposed that they go for a walk. My father was immense- ly proud of a great crested grebe which nested on our lake — the Shore Pool and he wanted to show the grebe to Waugh. The latter was violently opposed to the plan. Alcohol had flowed that day and Waugh objected that 'the poisons ought to be allowed to settle'.

My father won, and my parents set off, dragging their reluctant guest with them. Eventually the party got to the Shore Pool and sighted the grebe. Waugh was furious at its inadequacies and gave vent to his feelings: 'It's a pathetic bird, a miserable bird, a wretched bird.'

A few months later Waugh began Scoop, and the grebe became immortal. William Boot, the hero, first appears while he is writing a weekly nature column called 'Lush Places'. William is in despair over an article on badgers. His sister, out of mis- chief, had substituted 'the great crested grebe' for 'badger' throughout his piece, and William had received indignant com- plaints from his readers. One nature lover

challenged him categorically to produce a single authenticated case of a great crested grebe attacking young rabbits

— and so William's adventures begin. Sent to Africa to report on the war in Ishmaelia, William is a hopeless war correspondent. As the book reaches its climax, the grebe has become a god. William, in a slough of despond, bows his head:

'Oh, great crested grebe,' he prayed, `maligned fowl, have I not expiated the wrong my sister did you?'

The grebe answers William's prayer, and as a result, William gets the 'scoop' of the title.

But even this mockery of the grebe did not appease Waugh's fury over the infamous walk with my parents. Twenty years later he wrote The Life of Ronald Knox. Contempt for the great crested grebe smoulders in Waugh's pointed description of the Shore Pool, `. . . a lake which has afforded pleasure to ornithologists'.

On one of Waugh's visits to Aldenham, my mother's younger brother, Hedley Strutt, was a fellow guest. After dinner, Uncle Hedley beamed and said: 'I am going upstairs to see Nanny.' Waugh was riveted. 'Why is he going to do that?' he asked. My mother explained that Nanny Galer, who looked after my sister Pelline, had been Hedley's nanny and that, although now in his early twenties, Hedley still doted on her. Waugh showed such interest that my mother believes the episode contributed to the bond between Sebastian Flyte and his nanny in Brideshead Revisited.

The friendship continued to grow. My father, whom Waugh later described in one of his books as 'a light-hearted, sweet- tempered, old-fashioned, horsy young man,' adored roulette. Waugh accompa-

A damsel in distress — goody!' vied him and my mother to Ostend so that my father could indulge himself at the casino. When Waugh was to remarry, he brought his fiancee, Laura Herbert, to meet my parents at Aldenham.

The second world war ended such week- ends, and after the war my parents sold Aldenham and bought a farm called M'bebi, 25 miles from Salisbury (today's Harare). There they settled with their family of six children, which by 1954 had grown to ten. Evelyn Waugh re-entered my parents' lives when Ronald Knox — Ronnie to our family — died in 1957. Ronnie was an eminent priest and scholar, and had entrusted Waugh, a Catholic convert, with his biography. During his eight years at Aldenham, Ronnie had translated almost the entire Bible. As my mother had known Ronnie so well, Waugh flew out to Rhodesia in early 1958 and spent a month cross-examining her at M'bebi.

My first glimpse of Waugh was striking. My father's idea of dressing for dinner after his business day in Salisbury was to remove his jacket and come into the drawing room in open-necked shirt and trousers. We boys wore khaki shirts and shorts and had bare feet, often streaked with mud from the farm. On the evening Waugh reached M'bebi, I came straight from the dairy and wandered into the drawing-room barefooted and dressed as usual. A vision greeted me of a short, stout, red-faced man wearing an immaculate white dinner jacket, a garment I had only seen in films. When my mother introduced us, he glared at me. Shamed, I rushed off, put on socks and shoes, combed my hair, and reappeared. Evelyn Waugh had arrived.

After dinner my father waved airily down the passage which stretched the whole length of our vast bungalow. 'You see, Evelyn, it is like a ship with cabins on each side,' he said. To us children, M'bebi was simply home, and we were amused by Waugh's description of its eccentric features, which he recorded in a letter to Ann Fleming : Children were everywhere, no semblance of a nursery or a nanny, the spectacle at meals gruesome, a party-line telephone ringing all day, dreadful food, an ever present, tremen- dously boring ex-naval chaplain, broken aluminium cutlery, plastic crockery, ants in the bed, totally untrained black servants (all converted by Daphne to Christianity, taught to serve Mass but not to empty ash-trays). In fact everything that normally makes Hell, but Daphne's serene sanctity radiating super- natural peace. She is the most remarkable woman I know.

True, our ash-trays were in much use, as many of us chain-smoked cigarettes. Waugh added to the overflow by constantly smoking huge cigars. I was now, at 16, officially allowed to drink alcohol. But Waugh astonished me by drinking beer at breakfast. We children concluded that this was because he found our family so stunningly boring.

Although only 54, Waugh made a pantomime of being an old man. His chief prop was an enormous ear-trumpet, which he laid in front of him at meals. At lunch one day, the conversation turned to vocab- ulary. For reasons which are beyond me, I announced that I had a large vocabulary. This was too much for Waugh. His eyes blazing, he picked up the ear-trumpet and put it to his right ear. Omitting to make me repeat myself, he said: 'My dear boy, you only know about 200 words.' I still cringe when I hear the word 'vocabulary'.

Waugh was diverted by all of my sisters, who used various methods to make an impression on him. Catherine, two years my senior, determined to get on Christian- name terms with him. For somebody with her charm, this was not a very difficult task. But she made certain of it by bellowing 'Mr Waugh' towards the ear-trumpet at the end of every sentence. Eventually he gave in. `Won't you call me Evelyn?' he suggested graciously. My little sisters, Mary-Ann and Jane, decided that what our guest needed was entertainment. Waugh would sit trying to read his book, but found it impossible, as the little girls danced before him in varying degrees of dress and undress. Waugh pro- duced coins to persuade them to go away. But he never forgot their dancing and he ever after referred to them by the collective nickname 'the nautch girls' — Indian dancers.

Waugh was especially entranced by my sister Jill, known as Tickey. He conceived a plan that she should marry his eldest son, Auberon. His letters to my mother for Years are full of Jill. 'My love to all your hordes, especially Tickey.' After she had had an operation on her toes, he demand- ed furiously, 'Why have you cut off Tickey's feet?' Then he complained of a photograph showing dear Jill in a very had light. Young Auberon is not so keen & wants a nautch girl instead.' He was only to aban- don his dream in 1961, when Auberon got engaged.

Twenty years earlier in England, Waugh had lost the battle of the visit to the great crested grebe. Now in Rhodesia he won the battle to visit my married sister Pelline. My mother had pointed out that Pelline could not travel, as she was heavily pregnant and had three tiny sons, so Waugh insisted on going to see her instead. My mother urged that this was an impractical scheme, as Pelline had only three modest bedrooms. But Waugh was adamant, so my mother packed him, Father Maxwell (the 'ever pre- sent, tremendously boring ex-naval chap-

lain ), and her five youngest children into our Volkswagen bus and drove the 100

miles to Pelline's house. Pelline's entire

family huddled in one bedroom, Waugh had another, Father Maxwell the third. My

mother slept on the sofa and her children In the bus. After dinner, Waugh grew bored and went to bed early. He took a formidable sleeping draught of paralde- hyde, and soon terrible snores penetrated the thin ceilings and bounced off the tin roof. His roars woke my three- year-old nephew, Denes. 'Will a lion come?' he asked his parents.

Early in his visit to M'bebi, I showed Waugh the schoolroom which housed most of our books. Examining the shelves, he kept laughing. He was amused by the hap- hazard way that some great classic stood next to a book he dismissed as rubbish. I had always thought our books perfectly well arranged, but his laugh was so infec- tious that I found myself laughing with him.

Drinking tea on the stoep (as we called the verandah at M'bebi), my mother and I talked to Waugh about literature. I was reading Mansfield Park at school and asked him what he thought of Jane Austen. 'Very complete,' Waugh nodded. My brother Charlie and I adored P.G. Wode- house, and Waugh thought well of our taste. He quoted a sentence from Wode- house: 'I could see that, if not actually dis- gruntled, he was far from being gruntled.' No other author could possibly have writ- ten those words, Waugh emphasised with a chuckle.

My innocence at 16 emboldened me to ask Waugh some direct questions about his own books. When I had read Brideshead Revisited, it had struck me that Sebastian's mother, Lady Marchmain, was — like my mother — a beautiful Catholic peeress. So I blurted out: 'Is Lady Marchmain based on Mummy'?' Waugh, who had the highest opinion of my mother, but not of Lady Marchmain, burst out laughing.

My next question was more successful: 'What was the most difficult thing you ever did as a novelist'?' I asked. Without hesita-

tion, Waugh said: 'Turn a woman into a man.' I persisted: 'Who was the man?' 'Beaver in A Handful of Dust,' Waugh replied. Catherine and I had always laughed together at Beaver, the villain of the book. He had no personality and no job, but sat by the telephone hoping for invitations to meals. He was called 'London's only spare man'. Catherine had a fantasy that when I left school I might become Salisbury's only spare man. Now we knew that the model for Beaver was a woman.

The sequel to this story came 30 years later. I had read an article about A Handful of Dust by Auberon Waugh. He explained that Beaver, who wrecked the hero's marriage, was based on a man called John Heygate who had wrecked his father's first marriage. I wrote to Auberon and told him of the conversation I had had with his father. He replied: What you say rings a tiny bell. I believe that I may have heard my father say that ... Baby Jungman ... was at one time London's spare girl, waiting on the end of a telephone. It is possible that he shifted this one charac- teristic on to Heygate. If so, it might have been a double revenge, as he had been in love with Baby Jungman at one time. A curious idea.

Waugh went back to England in March 1958 and at Christmas that year my mother proudly sent a family photograph to all her friends and relations. Waugh's response was biting:

I say, what a photograph! I have been telling my family how pretty you all are & now you send them this very disillusioning group. Not like human beings at all.

Waugh's nostalgia for M'bebi was evi- dent when he wrote: 'It was touching to see the stain of the red earth of M'bebi on your letter'. and he duly returned in March

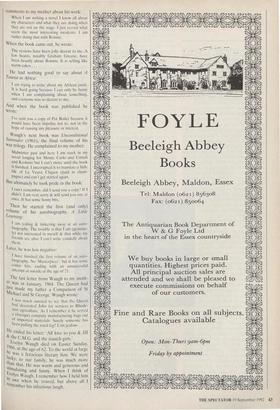

The Acton children at M'bebi, 1957, a jot. months before Waugh's first visit: from left to right, Jane, Mary-Ann, Peter, Edward, Jill, Robert, Charles, Richard, Catherine (Pelline was absent). 1959. This time he made a sponsored trip to east and central Africa an excuse to spend a fortnight with us. The fruit of this second expedition was A Tourist in Africa (1960). Here he describes his first day back at M'bebi:

The teeming life of the house, as in a back- street of Naples, rages round me from dawn to dusk, but I remain in my chair, subject to interrogation, and the performances of con- juring, dancing, and exhibitions of strength, but for one day at least immovable.

Much of Waugh's second visit was taken up with sightseeing. He, my mother, Father Maxwell and a young tycoon friend set off by car to see something of Rhodesia. The conspicuously red faces of Waugh and Father Maxwell inspired my father to chris- ten the group 'the Lobster Quadrille'. All went well until they got to the magnificent Zimbabwe ruins. At their hotel, the man- ageress insisted she had only one room with a bath. Waugh insisted that four rooms with baths had been booked. Their voices grew more and more heated, and the manageress sought to clinch the argu- ment. In a tone suggesting that they take their business elsewhere, she said: 'We like our guests to be happy.' Waugh trumped her with, 'I shouldn't think that happens very often.' My mother, as usual, resolved the matter — Waugh got the room with the bath.

During the Lobster Quadrille tour, Waugh found a way to tease our luckless chaplain, Father Maxwell, who summed up his intellectual life in the words, 'I read people, not books.' The priest, as his figure attested, enjoyed a glass of beer, and he was particularly fond of a cold Castle, Rhodesia's leading brew. At their first stop, Waugh asked Father Maxwell what he would like to drink. 'A co' Cussell,' Father Maxwell replied, with his heavy Manch- ester accent. From then on, every time they ordered drinks Waugh would triumphantly add: 'And a co' Cussell.'

But if Waugh mocked the man, he treat- ed the priest with respect. After his son had been appallingly injured in an accident, a grateful Waugh wrote to my mother: `Please thank Father Maxwell awfully for saying Mass for Bron.'

Waugh had the virtue of generosity. which at times rewarded him materially. At the end of his second visit to Rhodesia, he gave a fine dinner party at a Salisbury restaurant in honour of my 19-year-old sister Catherine. After his return to England he reported gleefully: 'My income tax man passed the bill for Catherine's Portuguese wine as a necessary literary expense.'

A special joke was born over The Life of Ronald Knox, which came out in 1959. Waugh dedicated the book to Katharine Asquith and my mother. Mrs Asquith, whose guest Ronnie had become when we emigrated to Rhodesia, read the book in proof. She wrote to my mother that it was a masterpiece. My mother in turn wrote to Waugh, 'Katharine says the book is a masterpiece.' From then on, Waugh always referred to the book in his letters to my mother as 'Masterpiece', and turned the joke into a bibliophile's treat. On publication, he sent my mother two copies. In the ordinary edition he wrote: 'This for bottom shelf.' He inscribed the special edition: 'For Daphne with my love and gratitude from Evelyn. This one is for the top shelf.' The title page read: 'The Life of the Right Reverend Ronald Knox . . . A MASTERPIECE by Evelyn Waugh.' He had had this volume specially printed for my mother. My brother Edward is now its proud owner; my mother, seeing me green with envy, presented me with the 'bottom shelf copy.

My mother's brothers, and indeed my father, had gone to Cambridge; my mother's friends had gone to Oxford. She was more impressed by the education of her friends than her relations. So, in 1959, she persuaded me to try for Trinity College, Oxford. Waugh joined in the plan, and on a visit to Oxford sought to insinuate me into Trinity. He reported to my mother: I told the President how lucky he was to be getting a promising scholar like Richard. He said: 'Yes, I hope very much he gets in.' Not an absolutely satisfactory answer.

I will never know if Evelyn Waugh influ- enced the result, but I managed to pass the entrance exam. I wanted to tour Italy and France before going to England, so my mother asked Waugh if he could suggest any friends to entertain me on the conti- nent. Complaining, as usual, about my Rhodesian accent, Waugh pointed out some of my other inadequacies: 'Poor chap, he has lived among bungalows and skyscrapers and won't know the difference between Classic, Gothic and Baroque.' As to hostesses in Europe: I don't see Richard being at all easy in cosmopolitan society — e.g. Nancy Mitford or Diana Cooper or Pam Churchill. He must get some English polish before we put him into circulation.

He sensibly concluded: 'Richard shall take Europe very slowly and humbly.'

After some months on the continent in the first half of 1960, I arrived in England. Masses of English people had stayed at M'bebi and, as a naive 18-year-old, I expected reciprocal invitations to flow. They did not. However, Waugh came up trumps, and promptly asked me to stay at Combe Florey. I had a happy weekend there. Auberon told me about Oxford, and I told his mother about our Jersey cows at M'bebi. Waugh talked of people and books, expressing particular admiration for the work of Muriel Spark. I played chess with Auberon, and there was a dinner party for relations on Saturday night. On Sunday, I went to Mass with the Waughs. We had a conversation at lunch Sunday about thank-you letters. I loathed writing letters and asked in a voice of despair if I had to write and thank for the weekend. Laura Waugh kindly said 'no', Evelyn Waugh firmly 'yes'. He went on to suggest possible topics for my letter, and made me rock with laughter. After much discussion, he concluded that it would be best for me to make some uncontroversial remarks about the weather and the Sunday sermon. I did write a thank-you letter, and Waugh wrote his own letter about the weekend to my mother:

I asked [Richard] with the promise that there would be a house-party, but one by one the other guests chucked & took ill, and in the end he was alone. He was a pineapple .0f politeness. The last year has transformed him from a Rhodesian schoolboy into a pre-1914 undergraduate. His accent has almost gone, his spots entirely. . . How cleverly he disguised his boredom, which must have been acute.

I was not in the least bored at Combe Florey, but I was, as always, daunted by my host. Having lost my watch, I was terrified of being late when the family set out for Mass on Sunday. Waugh discovered me pacing the hall ages before the appointed hour. He wrote to my mother:

[Richard] has no watch and is disconcerted by English habits of punctuality.

Catholicism was Waugh's conviction, writing his craft. His one communication to my father which survives shows to perfection his mastery of succinct prose. He knew that in Rhodesia my father sorely missed the roulette wheel. From Monte Carlo he sent him a picture postcard of the casino. The message consisted of one word.

`Homesick?'

'Sl< From the time he was engaged on The Life of Ronald Knox, Waugh made pithy

comments to my mother about his work: When I am writing a novel I know all about my characters and what they are doing when they arc not on the stage. I just record what seem the most interesting incidents. I am rather doing that with Ronnie.

When the book came out, he wrote:

The reviews have been jolly decent to me. A few beasts, notably Graham Greene, have been beastly about Ronnie. It is selling like warm cakes ...

He had nothing good to say about A Tourist in Africa:

1 am trying to write about my African jaunt. It is hard going because I can only be funny when I am complaining about something, and everyone was so decent to me.

And when the book was published he wrote:

I've sent you a copy of Pot Boiler because it would have been impolite not to, not in the hope of causing any pleasure or interest.

Waugh's next hook was Unconditional Surrender (1961), the final volume of his war trilogy. He complained to my mother:

Midwinter past and here I am stuck in my novel longing for Monte Carlo and Umtali and Kashmir but I can't move until the hook is finished. I interrupted it to translate a little life of La Veuvc Cliquot (paid in cham- pagne) and can't get started again.

But ultimately he took pride in the hook:

I can't remember, did I send you a copy? If I didn't, I am very sorry & will send you one at Once. It has some funny bits.

Then he started the first (and only) volume of his autobiography, A Little Learning:

I am toiling & tinkering away at an auto- biography. The trouble is that I am (genuine- ly) not interested in myself & that while my friends are alive I can't write candidly about them.

Later, he was less negative:

► have finished the first volume of an auto- biography. No 'Masterpiece'. but it has some comic bits, ending, with an unsuccessful attempt at suicide at the age of 21.

The last letter from Waugh to moth- Fr was in January, 1964. The Queen had Just made my father a Companion of St Michael and St George. Waugh wrote:

was much amused to see that the Queen had decorated John for services to Rhode- sian agriculture. As I remember it he served a (foreign) company manufacturing bags out of imported materials. Surely someone has been pulling the royal leg? I am jealous .

He ended his letter: 'All love to you & Jill the C.M.G. and the nautch girls.' - Evelyn Waugh died on Easter Sunday,

1966, at the age of 62. To the world at large he was a ferocious literary lion. We were LickY; to our family, he was much more than that. He was warm and generous and stimulating and funny. When I think of Evelyn Waugh, 1 remember how I held him In awe when he roared, but above all I remember his infectious laugh.

Previous page

Previous page