ARTS

Exhibitions 1

London — World City 1800-1840 (Villa Hugel, Essen, till 8 November)

Portrait of a city

Alan Powers

It seems perverse to go to Essen in the Ruhr to see an exhibition about London, but London — World City 1800-1840 is no ordinary exhibition. The Villa Hiigel, in a leafy setting outside the town, was once the residence of the Krupp family, and the financial backing of the post-war Krupps industrial empire through the Kultur- stiftung Ruhr has supported a series of exhibitions at the villa, each taking a city during a formative time in its history.

The period of the Napoleonic wars and their aftermath created a London which we can still see and inhabit. I write this in the basement of a house of 1816, within sound of St Pancras Parish Church bells, 'a very classical, ornamental, Grosvenor-Square- like kind of edifice ... a very elegant sort of place for a very elegant sort of party', built by William and Henry William Inwood a year or two later. Not far away in Gower Street, one hardly needs to see the 'Auto-icon' of Jeremy Bentham in Univer- sity College (temporarily transported in its mahogany case to Essen) to sense how that section of London is dedicated to a Utili- tarian approach to learning. Yet ten min- utes' walk brings one to Regent's Park, still a flourishing demonstra- tion of the flexible architectural ideas and picturesque inspiration of John Nash.

What the exhibition aims to achieve, as much through its 624- page catalogue (published in English by Yale University Press at £45 and edited by Celina Fox, who chaired the working party for the exhibition) as through its assembled objects, is a thematic survey of material culture in a city, encompassing objects traded as well as objects manufactured, political and urban history, science and art. These themes are set out in catalogue essays, following the main sections of the display.

The first sight at the head of the town-hall-scale stairs of the Villa Hugel is a reconstruction of George IV's Coronation proces- sion of 1821. Here are the cos- tumes in which the peers seem without undue dismay to have courted ridicule by looking like theatrical extras, to satisfy their monarch's love of fancy dress. An essay by Valerie Cumming extracts the humour and pathos of the occasion, the last such ancien regime-style event of its kind, but also a harbinger of the antiquari- an obsession with the past explored in another essay by Clive Wainwright.

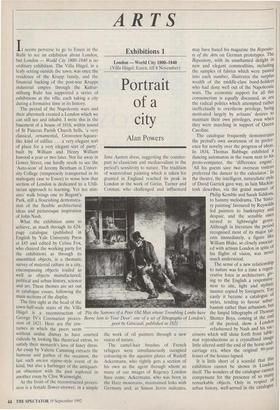

At the front of the reconstructed proces- sion is a female flower-strewer, in a simple Jane Austen dress, suggesting the counter- part to classicism and mediaevalism in the period's sensitivity to nature. The tradition of watercolour painting which is taken for granted in England reached its peak in London in the work of Girtin, Turner and Cotman, who challenged and influenced 'Pity the Sorrows of a Poor Old Man whose Trembling Limbs have Borne him to Your Door': one of a set of lithographs of London's poor by Gericault, published in 1821

vision of nature. mat reproductions as a crystallised image The camel-hair brushes of French little altered until the end of the horse-and- refugees were simultaneously occupied carriage era, when the original 99-year colouring-in the aquatint plates of Rudolf leases of the houses lapsed.

Ackermann, who rightly gets a section of It is little short of a scandal that this his own as the agent through whom so exhibition cannot be shown in London many of our images of Regency London

urban history, well-served in the catalogue the Harz mountains, maintained links with may have based his magazine the Reposito- ry of the Arts on German prototypes. The Repository, with its unashamed delight in new and elegant commodities, including the samples of fabrics which were pasted into each number, illustrates the surplus wealth of the middle-class bond-holders who had done well out of the Napoleonic wars. The economic support for all this consumerism is equally discussed, as are the radical politics which attempted rather ineffectually to overthrow privilege, being motivated largely by artisans' desires to maintain their own privileges, even when they were marching in support of Queen Caroline.

The sense of a new relationship to nature was for a time a regen- erative force in architecture, r- ing to the English a responsive- ness to site, light and stylistic nuance copied by foreigners. To easily it became a catalogue of styles, tending to favour subur- banism rather than urbanism, but the limpid lithographs of Thomas Shotter Boys, coming at the end of the period, show a London

refashioned by Nash and his suc- by Andrew Saint, did the display seem rather weak, and Londoners can at least compensate for missing Essen by reading the book and walking the familiar streets, perhaps taking in a visit to Sir John Soane's Museum in Lincoln's Inn Fields, with a new knowledge and awareness. For the rest, a journey to Essen is the best substi- tute — the nearest thing to time-travelling.'

Previous page

Previous page