Riding the Flood

From KENNETH MACKENZIE CAPE TOWN THMOS are moving fast and violently in South Africa. It is a different country from the one we lived in a fortnight ago. A massacre at Sharpe- vine, a riot in our usually so peaceful Cape Peninsula, and an unsuccessful but frightening anti-pass campaign by the Pan-Africanist Con- gress have been enough to pierce the sunburnt smugness of the Whites. For years liberals have been making Cassandra-like cries about impend- ing bloody disaster; now the mass of the Whites have come to realise, emotionally in their stomachs, that these are not wild propaganda but statements of the literal probabilities. As the Pan-Africanists' compaign gets over- taken by the bigger struggle between the African National Congress and the Government, there is In Cape Town an almost tangible atmosphere of expectant nervousness, a heaviness in the air strongly reminiscent of the 1939-40 days. Wild rumours follow one another in quick succession around the town; people are not sleeping well and easily lose their tempers; newspapers are snapped up; and all the time the talk, goes on and on and nn, at a high level of intensity and always on the same subject. People are queueing for guns, and the Canadian authorities report that inquiries from would-be immigrants have increased five- fold.

There is no doubt that many of the governing Afrikaners arc rattled. Die Burger, the most Influential of the Nationalist newspapers, has had 4 series of leaders verging on panic. They have made a desperate plea for a review of government PnlieY toward's Africans in the towns, 'even if it means that some established attitudes have to be changed.'

fir. Verwoerd will, of course, fight. We are going to have a rough few months. But there are signs that the pass is being quietly sold behind 4 „Int We cannot expect that we will wake up to- 'orrow in a democratic country. But I think we can expect a change in direction. 'Established attitudes' will give way and instead of standing Shaking our fists at the flood we•will set about finding some way of riding it. . the. will have to look a little more closely at t _lie. Pan-Africanist Congress. When they an- nounced their plans for the anti-pass campaign tn ?ere was a griod deal of sniffing in well-informed circles. Their record since they broke away from the Africa National Congress about eighteen Months ago has been one of very big talk—in spite of being a tiny organisation they have a full-scale shadow cabinet, including a Minister Of Defence and a Minister of Social Welfare-

but very little action. Their plan to persuade every African to surrender his pass to the police and then stay away from work seemed hopelessly over-ambitious. And it did fail by objective standards. Only a handful responded in and around Johannesburg, where all political cam- paigns are made or broken. Virtually no one came out in Durban, Port. Elizabeth and East London, where the ANC is strong. But they did have enormous success in Vereeniging and in Cape Town.and the unrestrained (to put it mildly) behaviour of the police in both places boosted the Pan-Africanists right into the world headlines.

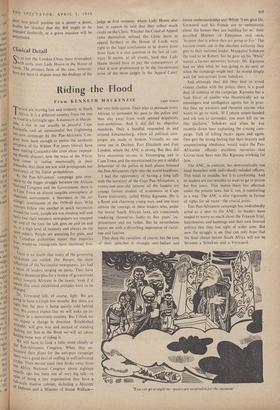

I had the opportunity of having a long talk with the secretary of the Cape Pan-Africanists, a twenty-one-year-old (almost all the leaders are young) former student of economics at Cape Town University, called Philip Kgosana. He is a fluent and charming young man, and one must admire the courage of these leaders who, under the brutal South African laws, are consciously rendering themselves liable to five years' im- prisonment and ten lashes. But he nevertheless leaves me with a disturbing impression of racial- ism and fascism.

They deny the, racialism, of course, but the tone of their speeches is strongly anti-Indian and (more understandably) anti-White. 'I am glad Dr. Verwoerd and his friends are so enthusiastic. about the houses they are building for us,' their so-called Minister of Education said once, 'because that is where they are going to live.' The fascism comes out in the absolute authority they give to their national leader, Mangaliso Sobukwe (he used to be Robert, but he gave up his 'White' name). a former university lecturer. Mr. Kgosana had no idea what he was going to do next or when the campaign might end: he would simply wait for instructions from Sobukwe.

And although they did their best to avoid violent clashes with the police, there is a good deal of violence in the campaign. Kgosana has a 'task force' of youths who theoretically act as messengers and intelligence agents but in prac- tice beat up waverers and threaten anyone who wants to go to work. 'If I return empty-handed and ask you to surrender, you must kill me on this platform,' Sobukwe said when he was recently down here explaining the coming cam- paign. Talk of killing recurs again and again. One gets the strong feeling that their bravery and unquestioning obedience would make the Pan- Africanist officials excellent terrorists—that Grivas must have men like Kgosana working for him.

The ANC, in contrast, has democratically run local branches with individually-minded officers. This leads to muddle, but it is comforting. And its leaders are too sensible to want to go to prison for five years. This makes them less effectual under the present laws, but it, too, is comforting in a way. The ANC is also vigorously in favour of rights for all races—the crucial point.

This Pan-Africanist campaign has undoubtedly acted as a spur to the ANC; its leaders have tended to worry so much about the Treason Trial, banishments and bannings and their own internal politics that they lost sight of wider aims. But now the struggle is on. One can only hope that the final choice before South Africa will not be between a Sobukwe and a Verwoerd.

Toll can gostruight in—passes are suspended for the moment.'

Previous page

Previous page