AFTER YOU, HELMUT

From domestic VAT rates to the recognition of Croatia, Britain is now meekly falling in with German policies.

Boris Johnson explains why we have given up so much

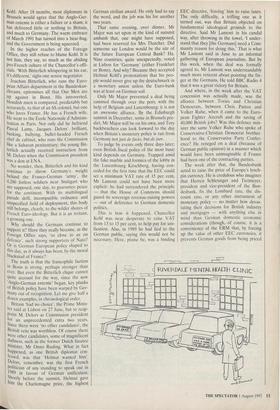

WHEN John Major flew in his BAe 146 to Bonn on 11 March 1991, prime minister for just three months, on his first bilateral trip to another EEC country, he turned, says the Foreign Office, a new page in our island story. With his `Heart of Europe' speech to the Konrad Adenauer Founda- tion, he won the tentative sympathy of Hel- mut Kohl; on that day he forged the first link of an 'Anglo-German alliance' — at once revolutionary and logical — which, nine months on, rescued Britain from isola- tion at Maastricht and changed the balance of power in Europe. That, at least, is the Foreign Office line.

From that day on, while Paris choked with jealousy, our Prime Min- ister became `Chohnny Major' to the powers in Bonn; and Herr Kohl was awarded the stock epithet 'avuncular' in the British press.

`You should have seen him [Kohl] at Maastricht,' the Foreign Office line goes on: it was midnight in that pill-box on the river Maas, the last table round, the last topic. Like some paternal pachyderm, Kohl had protected the British opt-outs and opt- ins against the federalist darts. Mitterrand

was exhausted and mutinous. Twice, finally, 11 countries asked Mr Major if he would abandon the use of the national veto in the EEC's new competence for 'research and technology', and twice he chirpily refused; and, British officials reminisce, just as the French President turned to him to point out, poisonously, that this was a community — do you know what? Helmut just roared with laughter.

It was a mixture of admiration at his cheek, say the British, and, dare one specu- late, a sort of avuncular pride; at any rate, they say, Helmut snorted and howled until

the chairman, the Dutch prime minister, Ruud Lubbers, gave up, and that was the end of the Maastricht Summit.

Of course, the mandarins aver, it was not just John Major's charm that did the trick. Six months before that flight to Bonn, amid the suspicions of Prime Minister Thatcher, the seeds were being quietly prodded in. Chris Patten, Tory party chairman, had been out to Bonn to see his opposite num- ber in the German Christian Democrats, Herr Volker Ruhe, with a view to some kind of inter-party pact in the European parliament. Ruhe spoke, unobtrusively, at the Conservative Party Conference in October 1990; by the time Mr Major replied in Bonn, after the Tory putsch in November, German CDs and British Tories had become ideological kinsmen if, again, you believe the rhetoric.

A big role, too, is credited to Sir Christo- pher Mallaby, the sepulchral, Charles Addams cartoon figure who has been Our Man in Bonn for the last five years, the man who bore the brunt of the Thatcher- Ridley plain-speaking on Germany. It was more than just an ambassadorial coup to secure the first prime ministerial visit to an EEC ally; it was a chance to suture the rents in the bilateral relationship.

But, you know, say the British diplomats, even so we just weren't prepared for the per- sonal feeling, the chem- istry — a joy intensified by memories of the cor- dial loathing between Kohl and Thatcher. Now, the two leaders greet each other, appar- Well, well, perhaps there really is some spark of mutual regard here, between the self-effacing Tory fixer from Brixton and the chortling tripe-eater from the Rhineland (who can communicate with each other only through interpreters). If there is, it is being adroitly utilised by Herr

Kohl. After 18 months, most diplomats in Brussels would agree that the Anglo-Ger- man entente is either a failure or a sham; it has delivered little or nothing to Britain, and much to Germany. The warm embrace of March 1991 has turned into a bear-hug, and the Government is being squeezed.

In the higher reaches of the Foreign Office, they still refuse to blame Kohl. It is not him, they say, so much as the abiding pro-French culture of the Chancellor's offi- cials. 'With Bitterlich whispering in his ear, it's different,' sighs one senior negotiator.

Joachim Bitterlich, who runs the Euro- pean Affairs department in the Bundeskan- zleramt, epitomises all that Our Men are up against in Bonn. His introverted, blondish mien is compared, predictably but accurately, to that of an SS colonel, but one who loves France. He has a French wife. He went to the Ecole Nationale d'Adminis- tration in Paris. Not only did he befriend Pascal Lamy, Jacques Delors' brilliant, barking, bullying, bullet-headed French chef de cabinet, who runs the Commission like a Saharan penitentiary; the young Bit- terlich actually received instruction from M. Delors when the Commission president was a don at ENA.

No wonder, then, Bitterlich and his kind continue to throw Germany's weight behind the Franco-German 'army', the 4,200 listless soldiers near Stuttgart who are supposed, one day, to guarantee peace for the continent. With its multilingual parade drill, incompatible ordnance and unspecified field of deployment, this body still belongs, clearly, to the wilder shores of French Euro-ideology. But it is an irritant, a growing one.

Why should the Germans continue to support it? Have they really become, as the Foreign Office says, 'so close to us on defence', such strong supporters of Nato? Or is German European policy shaped to this day, as it always has been, by the moral blackmail of France?

The truth is that the francophile faction in Bonn is strong, perhaps stronger than ever. But even the Bitterlich clique cannot quite account for the way, since the new 'Anglo-German entente' began, key planks of British policy have been warped by Ger- many out of recognition. Let me give half a dozen examples, in chronological order.

Britain 'had no choice', the Prime Minis- ter said at Lisbon on 27 June, but to reap- Point M. Delors as Commission president for an unprecedented extra two years. Since there were 'no other candidates', the British veto was worthless. Of course there were other candidates, some of magnificent dullness, such as the former Dutch finance Minister, Mr Onno Ruding. What in fact happened, as one British diplomat con- fessed, was that 'Helmut wanted him'. Delors, remember, was the first French Politician of any standing to speak out in 1989 in favour of German unification. Shortly before the summit, Helmut gave him the Charlemagne prize, the highest

German civilian award. He only had to say the word, and the job was his for another two years.

That same evening, over dinner, Mr Major was set upon in the kind of summit ambush that, one might have supposed, had been reserved for Mrs Thatcher. Did someone say London would be the site of the future European Central Bank? Ha. Nine countries, quite unexpectedly, voted at Lisbon for 'Germany' (either Frankfurt or Bonn). And why? Because they accepted Helmut Kohl's protestations that his peo- ple would never give up the deutschmark in a monetary union unless the Euro-bank was at least on German soil.

Only Mr Major prevented a deal being rammed through over the port, with the help of Belgium and Luxembourg; it is not an awesome alliance. By the Edinburgh summit in December, some in Brussels pre- dict, Mr Major will be on his own, and Tory backbenchers can look forward to the day when Britain's monetary policy is run from Germany not just de facto, but de jure.

To judge by events only three days later, even British fiscal policy of the most basic kind depends on Germany. Trapped amid the fake marble and formica of the lobby in the Luxembourg Kirschberg, having con- ceded for the first time that the EEC could set a minimum VAT rate of 15 per cent, Mr Lamont could not have been more explicit: he had surrendered the principle — that the House of Commons should guard its sovereign revenue-raising powers — out of deference to German domestic politics.

This is how it happened. Chancellor Kohl was near desperate to raise VAT from 13 to 15 per cent, to help pay for uni- fication. Alas, in 1989 he had lied to the German public, saying this would not be necessary. Here, praise he, was a binding

EEC directive, 'forcing' him to raise taxes. The only difficulty, a trifling one as it turned out, was that Britain objected on fundamental ideological grounds to the directive. Said Mr Lamont in his candid way, after throwing in the towel, 'I under- stand that they [the Germans] need a Com- munity reason for doing this.' That is what Mr Lamont said in June to an informal gathering of European journalists. But by this week, when the deal was formally agreed to, Mr Lamont was understandably much more reticent about pointing the fin- ger at the Germans. He told BBC Radio 4 that it was a great victory for Britain.

And where, in the week after the VAT concession was actually made, was the alliance between Tories and Christian Democrats, between Chris Patten and Volker Ruhe, when it came to the Euro- pean Fighter Aircraft and the saving of 40,000 British jobs? Was this defence min- ister the same Volker Ruhe who spoke of Conservative-Christian Democrat brother- hood to the Conservative Party Confer- ence? He reneged on a deal (because of German public opinion) in a manner which would have been unimaginable if France had been one of the contracting parties.

The week after that, the Bundesbank acted to raise the price of Europe's lynch- pin currency. He is credulous who imagines that Herren Schlesinger and Tietmeyer, president and vice-president of the Bun- desbank, fix the Lombard rate, the dis- count rate, or any other instrument of monetary policy — no, matter how devas- tating their decisions for British industry and mortgages — with anything else in mind than German domestic economic considerations (though,. of course, it is a convenience of the ERM that, by forcing up the value of other EEC, currencies, it prevents German goods from being priced

out of the European market). Much has been said lately on this, and there is no need to expand.

And, finally, at the risk of repetition, it was for German domestic political reasons that the EEC was dragooned into recognis- ing Croatia, now perceived in Whitehall as the most catastrophic error of the last year. That laid what Lord Carrington has called the 'powder trail' directly to the present detonations in Bosnia. Douglas Hurd has never seemed so upset — not just miffed, or out of sorts — as when, in the early hours of last 16 December in Brussels, Hans-Dietrich Genscher threatened inde- pendent recognition, and effectively held a gun to the head of the rest of the Commu- nity.

Before acceding to German wishes for a joint action, Mr Hurd — on the rack of conscience — stressed, uncharacteristically, that he had telephoned Mr Major (who was at Jeffrey Archer's cocktail party) for advice. He knew it was a dreadful, miscon- ceived policy. But Kohl wanted it, for his Croatian minority, but mainly because of public opinion and German theories of self-determination. Major approved, it was acknowledged, because it went with the `deal' at Maastricht.

Even if they accept, or partly accept, the strength of this handful of points, govern- ment officials retort snappily, 'Well, at least we've got a big power ally in Europe, which we never had under Thatcher.' Germany stands four-square with us, they say, on the crunch issues of the British presidency opening the Community to more members, pruning the excesses of the Delors budget. Others say Germany has yielded little to Britain, since that famous Major mission to Bonn, which it would not have given any- way. It is fairly predictable that Bonn should favour, as Britain does, the early accession to the EEC of Austria. Thereby it will achieve, at last, the effective economic anschluss which France always forbade the Teutonic tribes. As for the budget, is it really any surprise that Germany, paying both £6 billion net to the EEC and the price of unification, should admire finan- cial rigour?

Of course it is good to have allies in Europe. There is no alternative. But we are entitled to expect some balance in a rela- tionship, and here there is none. Perhaps, some would say, it is time for Mr Major to reflect on whether his friendship with the Chancellor is one of those political fealties he wishes to honour, in his own phrase, `through thick and thin'.

Kohl won a British signature on Maas- tricht. It seems odd, when one examines the fruits of the 'Anglo-German entente' in the succeeding seven months, that the preservation of that relationship should be given as one of the key reasons for ratifying the Treaty.

Boris Johnson is EEC correspondent for the Daily Telegraph.

Previous page

Previous page