A laughing butterfly

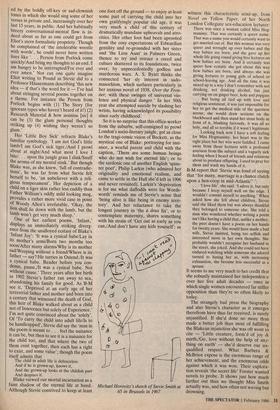

Michael Horovitz

STEVIE: A BIOGRAPHY OF STEVIE SMITH by Jack Barbera and William McBrien

Heinemann, £15

The English reviewing establishment seems to have closed its ranks against this first biography of the spritely sibyl Brian Patten has dubbed `Blake's purest daugh- ter'. For me it's a triumph of what the authors themselves concede is 'the Amer- ican tradition of the beaver, as opposed to the English tradition of the butterfly'. This is perfectly apt, since they are Americans from a younger generation than their subject, and never met her; since Stevie

Smith was — and her writings remain — so particularly butterflylike; and since these writings and other primary sources are so lavishly quoted throughout.

Messrs Barbera and McBrien (B-M hereafter) had already completed a salut- ary course of field-work by co-editing Me Again (Virago, 1981), their highly enter- taining and instructive miscellany of uncol- lected Stevieana. Among the thousands of papers they perused on their further re- searches was a soldier's fan letter saying, `You remind me of a laughing butterfly flickering over the head of James Joyce.' Stevie's flights of fancy, wordplay and imagination were faster and looser than Joyce's or Blake's — though the lightness could be deceptive, with serrated blades in its sheen or a subtle sting in the tail. She kept her muse free to be spontaneous, darting in and out of gardens and air pockets and shifting fairy woods their

grandiose master-plans forbade. Joyce's verbal-butterfly pub-crawls were passing diversions from an intently (and honour- ably) beaverlike pursuit not unlike that with which B-M track Stevie's progress. Their scholarship, at once resourceful and ingenious though by definition plodding, for the most part illuminates without dis- rupting its subject's complex impulses, movements and effects.

Nevertheless, Hermione Lee for one has rebuked them for making Stevie's life and work seem boring. She does this in much the same terms as I — perhaps too wasp- ishly — chided her Stevie Smith: A Selec- tion (from Faber, 'designed especially for students') in the Spectator on 24 November 1984. Sixty of B-M's 580 pages are made up of notes to their exposition — a smaller fraction than the 30 pages set aside in Miss Lee's 224. My calling the latter 'inapprop- riately laboured', and her extrapolations 'sometimes laughably perfunctory', seems to have touched a nerve, because her Observer piece on B-M (1 December '85) in turn accuses them of 'banal platitudes' and 'laborious ineptitude'. Yet — by con- trast to her book and to her review of theirs — B-M's commentaries are factual, judi- cious, pithy, always helpfully substantiated and scrupulously acknowledged. Miss Lee ridicules their 'worthy, foot-on-the- ground' approach, although the self- effacing beaver's industry is the very thing that keeps Stevie's elusively zig-zagging wings so steadily in focus. Any attempt to pin down her soul in words would be foolish indeed, but we should thank these men for giving us such a clear and un- assuming itinerary of its chronological manifestations.

The text is most charmingly embellished with photographs and drawings from every phase of her development, and the biog- raphers are particularly good on Stevie's sketches, and her relationship to other artists and writers:

. . . Often, next to poems about rejection, loss and despair, her childlike drawings playfully wink at the reader as if to say, 'it is legitimate to express anger or sorrow, but then one must laugh', or, 'this is a volume of poetry, but one need not be "serious" about it'. Stevie's decorating her text was subver- sive — not that other poets hadn't done so, other 'eccentrics' such as Blake and Lear. But doodles are personal, and T. S. Eliot had made popular the notion that good poetry is impersonal. It would have been as unlikely for him to decorate his serious poems with doodles as it would have been for him to sing them. During the heyday of New Criticism, poems were supposed to be well-wrought objects. Such a metaphor minimises the relevance of things external to the text. If Stevie's poetry is more fashionable today than it was in the '50s, so too is the metaphor of a poem as a voice. In terms of such a metaphor an author's drawing need not be dismissed as a frill or crutch, for it can be taken as another voice or statement. Whether a poem and drawing are in har- mony or counterpoint, and how they colour each other, become matters of interest.

It's true that the simultaneous grace and incongruity of her illustrations was match- ed by the boldly off-key or sad-clownish tones in which she would sing some of her verses in private and, increasingly over her last 15 years, in public. And her habitually breezy conversational-mental flow is in- deed about as far as one could get from Eliot's stern formalistic propriety. Though he complained of 'the intolerable wrestle with words', he could never have written lines like . . Person from Porlock come quickly/And bring my thoughts to an end./I am hungry to be interrupted/For ever and ever amen.' Nor can one quite imagine Eliot writing to Pound as Stevie did to a Professor Hausermann describing 'this new idea — if that's the word for it — I've had about stringing several poems together on a theme. For instance the Person from Porlock begins with (1) The Story (for ignorant types who haven't heard of it!) (2) Research Material & how assinine [sic] it can be (3) the glum personal thoughts striking up (4) wishing they weren't so glum.'

Her 'Little Boy Sick' refracts Blake's familiar symbology. 'I am not God's little lamb/I am God's sick tiger./And I prowl about at night/And what most I love I bite/. . . upon the jungle grass I slink/Snuff the aroma of my mental stink.' But though Blake was, as she knew, 'full of contradic- tions', he was far from what Stevie felt herself to be, 'an unbeliever with a reli- gious temperament'. Her depiction of a child on a tiger skin rather less cuddly than Father William's oddly mild looking mog, provides a rather more vivid case in point of Woody Allen's irrefutable, 'Okay, the lion shall lie down with the lamb, but the lamb won't get very much sleep.' One of her earliest poems, 'Infant,' displays an immediately striking diverg- ence from the unalloyed ecstasy of Blake's `Infant Joy': 'It was a cynical babe/Lay in its mother's arms/Born two months too soon/After many alarms/Why is its mother sad/Weeping without a friend/Where is its father — say?/He tarries in Ostend./It was a cynical babe. Reader before you con- demn, pause,/It was a cynical babe. Not without cause.' Three years after her birth in 1902 Stevie's father ran away to sea, abandoning his family for good. As B-M see it, 'Deprived at an early age of her terrestrial father and mother and born into a century that witnessed the death of God, this heir of Blake walked about as a child not of Innocence but solely of Experience.' I'm not quite convinced about the 'solely'. Of `To carry the child into adult life/Is to be handicapped', Stevie did say the 'man in the poem is meant to . . . feel the nuisance it can be, but then to see it is a nuisance for the child too, and that where the two of them exist together, then each has a right to exist, and some value'; though the poem itself admits that

The child in adult life is defenceless And if he is grown-up, knows it, And the grown-up looks at the childish part And despises it.

Blake viewed our mortal incarnation as a faint shadow of the eternal life at hand. Although Stevie contrived to keep at least one foot off the ground — to enjoy at least some part of carrying the child into her own gratifyingly popular old age, it was very much a child of this century of dramatically mundane upheavals and atro- cities. Her other foot had been uprooted from the cosy expectations of Edwardian gentility and re-grounded with her sister and 'the Lion Aunt' in Palmers Green, thence to try and retrace a creed and culture shattered to its foundations, twice over, by unprecedentedly godless and murderous wars. A. S. Byatt thinks she connected 'her sly interest in sado- masochism, which surfaces particularly in her anxious novel of 1938, Over the Fron- tier, with these swinges of universal vio- lence and physical danger.' In her 50th year she attempted suicide by slashing her wrists, having acknowledged its possibility since early childhood.

So it is no surprise that this office-worker from the suburbs, self-consigned to prowl London's socio-literary jungle, got as close to the tragi-comic vision of Beckett, as the mystical one of Blake: portraying for inst- ance, a woeful parent and child with the caption, 'There are some human beings who do not wish for eternal life'; or to the sardonic one of another English 'spins- ter poet', Philip Larkin (who admired her originality and emotional realism, and came to settle in the Hull she'd left in 1906 and never revisited). Larkin's 'deprivation is for me what daffodils were for Words- worth' reminds me of Stevie's sense that `being alive is like being in enemy terri- tory'. And her reluctance to take the longest journey in 'the a deux fix', or to contemplate maternity, shares something with his strain of 'Get out as early as you can,/And don't have any kids yourself: as Michael Horovitz's sketch of Stevie Smith at 65 in Brussels in 1967 witness this characteristic send-up, from Novel on Yellow Paper, of her North London Collegiate sex-education lecturer:

There was once a woman called Miss Hog- manimy. That was certainly a queer name. That was a name you would certainly want to get married out of. But this woman was very queer and wrought up over babies and the way babies are born, and she gave up her whole life going round giving free lectures on how babies are born. And it certainly was queer how ecstatic she got about this way how babies are born, and always she was giving lectures to young girls of school or school-leaving age. And all the time it was mixed up in a way I don't remember with not drinking, not drinking alcohol, but just carrying on on ginger beer, kola and popgass . . . But being all tied up with love and religious sentiment, it was just impossible for her to get the medical side of the question across; she would draw sections on the blackboard and then stand her stout body in front of it, blushing furiously, it was all so holy, and all so terrible if it wasn't legitimate . . . Looking back now I have a soft feeling for Miss Hogmanimy, her heart was in the right place but her wits were fuddled. I came away from those lectures with a profound aversion from the subject and a vaguely sick feeling when I heard of friends and relations about to produce offspring. I used to pray for them and wash my hands of it.

B-M report that 'Stevie was fond of saying that "for many, marriage is a chance clutch upon a hen-coop in mid-Atlantic" ': . . . 'I love life', she said, 'I adore it, but only because I keep myself well on the edge. I wouldn't commit myself to anything.' When asked how she felt about children, Stevie said she liked them but was always thankful they belonged to someone else. She told a man who wondered whether writing a poem isn't like having a child that, unlike a mother, the poet doesn't have a poem on her hands for twenty years. She would have made a bad wife, Stevie insisted, being too selfish and interested more in her own thoughts. She probably wouldn't recognise her husband in the street, she joked. And she could not have endured watching while someone she adored turned to hating her as, with increasing exhaustion, she became less successful as a spouse. It seems to me very much to her credit that she robustly maintained her independence over her five adult decades — ones in which single women encountered far stiffer opposition than they're so often likely to today.

The strangely bad press the biography and also Stevie's character as it emerges therefrom have thus far received, is surely unjustified. If she'd done no more than made a better job than most of fulfilling the Blakean injunction she was oft wont to cite — 'Little creature, form'd of joy & mirth,/Go, love without the help of any- thing on earth' — she'd deserve our un- qualified respect. What Barbera & McBrien expose is the enormous range of her achievement, and the enormous odds against which it was won. Their explora- tion reveals 'the secret life' Forster wanted novels to probe. It shows just how much farther out than we thought Miss Smith actually was, and how often not waving but drowning.

Previous page

Previous page