ARTS

Exhibitions

Reynolds

(Royal Academy till 31 March) Reconsider-

ing Reynolds

Giles Auty

Some of the odder misapprehensions of my early childhood arose through listening to adult conversation. One such was that the Dark Ages, which I had often heard my father mention, was a bygone period of uncertain date when life on this planet took place in semi-darkness. Nor was I without evidence for this particular notion. If asked, I would have cited the Stygian backgrounds in paintings by a long-dead hence, to my childish mind, 'dark-age' artist, Sir Joshua Reynolds, whose works I had looked at in reproduction.

Appropriately this odd little memory returned to me last week while walking through the imposing galleries of the in- stitution of which Sir Joshua had been the first President. Was the current Royal Academy exhibition to be a triumphant homecoming? Hardly so, since this historic show seems to have met, so far, with limited enthusiasm. Artists I have talked with are almost unanimous in their prefer- ence for the works of two of Reynolds's contemporaries: Gainsborough and Stubbs. Critics, too, have ranged from the luke- warm to the venomous. Has there been a complete change in sensibility or are we now moving closer to a more dispassionate assessment of the artist? Were we formerly misled by a misplaced sense of patriotic pride — although Reynolds has been much admired also in France? Indeed, the pre- sent exhibition has already been seen in Paris where it was generously praised.

Our current coldness to Reynolds first prompted my recollection of childhood. But surely it is not simply the dark back- grounds or lowering skies we object to? The use of chiaroscuro has never affected our enthusiasm for Caravaggio or Rem- brandt.

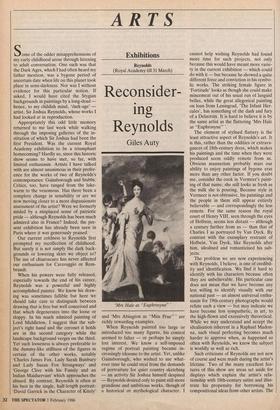

When his powers were fully released, especially towards the end of his career, Reynolds was a powerful and highly accomplished painter. We know his draw- ing was sometimes fallible but here we should take care to distinguish between drawing that is free but well conceived and that which degenerates into the loose or sloppy. In his much admired painting of Lord Middleton, I suggest that the sub- ject's right hand and the coronet it holds are in the second category while the landscape background verges on the third. Yet such looseness is always preferable to the dummy-like stiffness of the figures in certain of the other works, notably `Charles James Fox, Lady Sarah Bunbury and Lady Susan Fox Strangways' and `George Clive with his Family and an Indian Maidservant' which approaches the absurd. By contrast, Reynolds is often at his best in the single, half-length portrait: `David Garrick in the Character of Kitely' `Mrs Hale as "Euphrosyne" ' and 'Mrs Abington as "Miss Prue" ' are richly rewarding examples.

When Reynolds painted too large or introduced too many figures, his control seemed to falter — or perhaps he simply lost interest. We know a self-imposed regime of portrait painting became in- creasingly irksome to the artist. Yet, unlike Gainsborough, who wished to use what- ever time he could steal from the demands of portraiture for quiet country sketching — an activity Sir Joshua himself despised — Reynolds desired only to paint still more grandiose and ambitious works, though of a historical or mythological character. I cannot help wishing Reynolds had found more time for such projects, not only because this would have meant more varie- ty in the current exhibition — which could do with it — but because he showed a quite different force and conviction in his symbo- lic works. The striking female figure in `Fortitude' looks as though she could make mincemeat out of his usual run of languid belles, while the great allegorical painting on loan from Leningrad, 'The Infant Her- cules', has something of the dash and fury of a Delacroix. It is hard to believe it is by the same artist as the flattering 'Mrs Hale as "Euphrosyne" '.

The element of stylised flattery is the least attractive aspect of Reynolds's art. It is this, rather than the oddities or extrava- gances of 18th-century dress, which makes his paintings and the time when they were produced seem oddly remote from us. Obvious mannerism probably mars our ability to enjoy paintings of bygone eras more than any other factor. If you doubt me, consider the cook in Vermeer's paint- ing of that name; she still looks as fresh as the milk she is pouring. Because style in Vermeer is not obtrusive, his paintings and the people in them still appear entirely believable — and correspondingly the less remote. For the same reason the royal court of Henry VIII, seen through the eyes of Holbein, seems less distant — although a century further from us — than that of Charles I as portrayed by Van Dyck. By contrast with the exemplary restraint of Holbein, Van Dyck, like Reynolds after him, idealised and romanticised his sub- jects.

The problem we are now experiencing with Reynolds, I believe, is one of credibil- ity and identification. We find it hard to identify with his characters because often they are unbelievable. His particular case does not mean that we have become any less willing to identify visually with our national past — an almost universal enthu- siasm for 19th-century photographs would refute such a view — but may indicate we have become less sympathetic, in art, to the high-flown and excessively theoretical. While we may understand and accept the idealisation inherent in a Raphael Madon- na, such visual perfecting becomes much harder to approve when, as happened so often with Reynolds, we know the subject is worldly as well as rich.

Such criticisms of Reynolds are not new of course and were made during the artist's lifetime. Two of the many excellent fea- tures of this show are areas set aside for displays which explain the artist's rela- tionship with 18th-century satire and illus- trate his propensity for borrowing his compositional ideas from other artists. The catalogue, too, is excellent and the exhibi- tion, as a whole, a credit to its organisers.

From my own observations, visitors found the explanatory texts in each of the galleries interesting and helpful. One piece in particular summed up Reynolds's most serious fault to a nicety: 'Meanwhile he continued to transfuse his female portraits with the graces and attributes of ideal art and antique sculpture — and to subtract from them all evidence of the topical and familiar.'

Previous page

Previous page