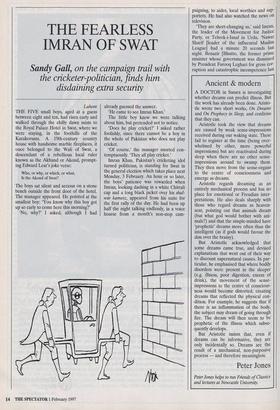

THE FEARLESS IMRAN OF SWAT

Sandy Gall, on the campaign trail with

the cricketer-politician, finds him disdaining extra security

Lahore THE FIVE small boys, aged at a guess between eight and ten, had risen early and walked through the chilly dawn mists to the Royal Palace Hotel in Swat, where we were staying, in the foothills of the Karakorums. A 19th-century country house with handsome marble fireplaces, it once belonged to the Wali of Swat, a descendant of a rebellious local ruler known as the Akhund or Akond, prompt- ing Edward Lear's joke verse: Who, or why, or which, or what, Is the Akond of Swat?

The boys sat silent and serious on a stone bench outside the front door of the hotel. The manager appeared. He pointed at the smallest boy: 'You know why this boy got up so early to come here this morning?'

`No, why?' I asked, although I had already guessed the answer.

`He came to see Imran Khan.'

The little boy knew we were talking about him, but pretended not to notice.

`Does he play cricket?' I asked rather foolishly, since there cannot be a boy in the whole of Pakistan who does not play cricket.

`Of course,' the manager snorted con- temptuously. 'They all play cricket.'

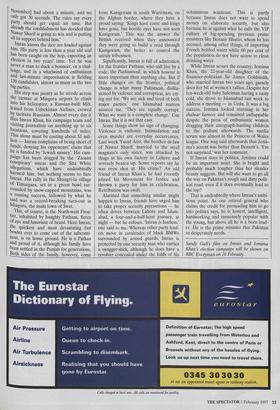

Imran Khan, Pakistan's cricketing idol turned politician, is standing for Swat in the general election which takes place next Monday, 3 February. An hour or so later, the boys' patience was rewarded when Imran, looking dashing in a white Chitrali cap and a long black jacket over his shal- war kameez, appeared from his suite for the first rally of the day. He had been up half the night talking endlessly, in a voice hoarse from a month's non-stop cam- paigning, to aides, local worthies and sup- porters. He had also watched the news on television.

`They are short-changing us,' said Imran, the leader of the Movement for Justice Party, or Tehrek-i-Insaf in Urdu. Nawaz Sharif [leader of the influential Muslim League] had a minute 20 seconds last night. Benazir [Bhutto, the former prime minister whose government was dismissed by President Farooq Leghari for gross cor- ruption and catastrophic incompetence last November] had about a minute, and we only got 30 seconds. The rules say every party should get equal air time. But already the establishment has decided that Nawaz Sharif is going to win and is putting all its support behind him.' Imran knows the dice are loaded against him. His party is less than a year old and has been caught on the hop, expecting an election in two years' time. Yet he was never a man to duck a bouncer, or a chal- lenge, and in a whirlwind of enthusiasm and last-minute improvisation is fielding 130 candidates, almost as many as the two big parties.

His step was jaunty as he strode across the tarmac at Mingora airport to climb into his helicopter, a Russian-built Mi8, leased from Uzbekistan Airlines, crewed by taciturn Russians. Almost every day it flies Imran Khan, his campaign team and visiting journalists on anything up to six locations, covering hundreds of miles. This alone must be costing about $1 mil- lion — Imran complains of being short of funds, denying his opponents' claim that he is funded by 'Jewish money'. His cam- paign has been dogged by the 'Zionist conspiracy' smear and the Sita White allegations, which have undoubtedly harmed him, but nothing seems to faze Imran. His rally in the Shangri-la village of Timargara, set in a green bowl sur- rounded by snow-capped mountains, was a rousing success, followed by what he said was a record-breaking turn-out in Mingora, the main town of Swat.

This, of course, is the North-west Fron- tier, inhabited by haughty Pathans, fierce of eye and luxuriant of beard. Here Imran, the quickest and most devastating fast bowler ever to come out of the subconti- nent, is on home ground. He is a Pathan and proud of it, although his family have been settled in the Punjab for generations. Both sides of the family, however, come from Kanigoram in south Waziristan, on the Afghan border, where they have a proud saying: 'Kings have come and kings have gone, but hostile eyes have not seen Kanigoram.' This was the answer the British received when they announced they were going to build a road through Kanigoram, the better to control the unruly tribesmen.

Significantly, Imran is full of admiration for the frontier Pathans, who still live by a code, the Pushtunwali, in which honour is more important than anything else. But if little changes on the frontier, political change is what many Pakistanis, disillu- sioned by violence and corruption, are cry- ing out for. 'We are sick and tired of both major parties,' one Islamabad matron assured me. 'They are equally corrupt. What we want is a complete change.' Cue Imran. But it is not that easy.

Some things show no sign of changing. Violence is endemic. Intimidation and even murder are everyday occurrences. Last week Yusuf Aziz, the brother-in-law of Nawaz Sharif, married to the steel magnate's only sister, was attacked by thugs at his own factory in Lahore and severely beaten up. Some reports say he was even shot at. His crime? An old friend of Imran Khan's, he had recently joined his Movement for Justice and thrown a party for him in celebration. Retribution was swift.

Alarmed that something similar might happen to Imran, friends have urged him to take proper security precautions — he often drives between Lahore and Islam- abad, a four-and-a-half-hour journey, at night — but he refuses. 'Imran is fearless,' one said to me. Whereas other party lead- ers move in cavalcades of black BMWs surrounded by armed guards, Imran is protected by one security man who carries a swagger-stick, although he does have a revolver concealed under the folds of his voluminous waistcoat. This is partly because Imran does not want to spend money on elaborate security, but also because he is against what he calls the VIP culture of big-spending previous prime ministers like Benazir Bhutto, whom he has accused, among other things, of importing French bottled water while 60 per cent of the population do not have access to clean drinking water.

While Imran scours the country, Jemima Khan, the 22-year-old daughter of the financier-politician Sir James Goldsmith, who married Imran two years ago, gamely does her bit at women's rallies. Despite her ten-week-old baby Suleiman having a nasty cold, she drove to Islamabad last week to address a meeting — in Urdu. It was a big success. Jemima looked stunning in her shalwar kameez and remained unflappable despite the press of enthusiastic women dragging their autograph-hunting children to the podium afterwards. The media scrum was almost in the Princess of Wales league. One wag said afterwards that Jemi- ma's accent was better than Benazir's. 'I'm not surprised,' was her comment.

If Imran stays in politics, Jemima could be an important asset. She is bright and probably much tougher than her slender beauty suggests. But will she want to go all the way on Pakistan's rough and dirty polit- ical road, even if it does eventually lead to the top?

That is undoubtedly where Imran's ambi- tions point. As one retired general who claims the credit for persuading him to go into politics says, he is honest, intelligent, hardworking and immensely popular with the young, but above all he is a born lead- er. He is the prime minister that Pakistan so desperately needs.

Sandy Gall's film on Imran and Jemima Khan's election campaign will be shown on BBC Everyman on 16 February.

Previous page

Previous page