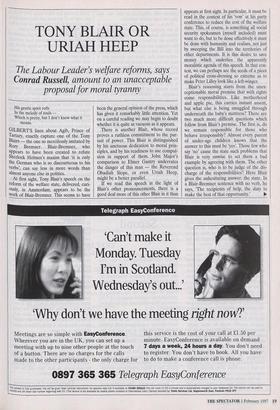

TONY BLAIR OR URIAH HEEP

The Labour Leader's welfare reforms, says

Conrad Russell, amount to an unacceptable

proposal for moral tyranny

His gentle spirit rolls In the melody of souls - Which is pretty, but I don't know what it means.

GILBERT'S lines about Agib, Prince of Tartary, exactly capture one of the Tony Blairs — the one so mercilessly imitated by Rory Bremner. Blair-Bremner, who appears to have been created to refute Sherlock Holmes's maxim that 'it is only the German who is so discourteous to his verbs', can say less in more words than almost anyone else in politics.

At first sight, Tony Blair's speech on the reform of the welfare state, delivered, curi- ously, in Amsterdam, appears to be the work of Blair-Bremner. This seems to have been the general opinion of the press, which has given it remarkably little attention. Yet on a careful reading we may begin to doubt whether it is quite as vacuous as it appears.

There is another Blair, whose record proves a ruthless commitment to the pur- suit of power. This Blair is distinguished by his unctuous dedication to moral prin- ciples, and by his readiness to use compul- sion in support of them. John Major's comparison to Elmer Gantry underrates the danger of this man — the Reverend Obadiah Slope, or even Uriah Heep, might be a better parallel.

If we read this speech in the light of Blair's other pronouncements, there is a good deal more of this other Blair in it than appears at first sight. In particular, it must be read in the context of his 'vow' at his party conference to reduce the cost of the welfare state. This, of course, is something all social security spokesmen (myself included) must want to do, but to be done effectively it must be done with humanity and realism, not just by sweeping the Bill into the territories of other departments. It is this desire to save money which underlies the apparently moralistic agenda of this speech. In that con- text, we can perhaps see the seeds of a piece of political cross-dressing so extreme as to make Peter Lilley look like a left-winger.

Blair's reasoning starts from the unex- ceptionable moral premise that with rights come responsibilities. Like motherhood and apple pie, this carries instant assent, but what else is being smuggled through underneath the baby's mattress? There are two much more difficult questions which follow from Blair's premise. The first is, do we remain responsible for those who behave irresponsibly? Almost every parent of under-age children knows that the answer to this must be 'yes'. Those few who say 'no' cause the state such problems that Blair is very unwise to set them a bad example by agreeing with them. The other question is, who is to be judge of the dis- charge of the responsibilities? Here Blair gives the unhesitating answer: the state. In a Blair-Bremner sentence with no verb, he says, 'The recipients of help, the duty to

make the best of that opportunity.' ► If the individual conscience were to remain the judge of that duty, this might be fair enough, but it is not. He adds, in a pas- sage which probably applies to the long- term unemployed as well as to the under-25s: 'There will be no option of a life permanently on full benefit. Where there is a suitable offer, people will be expected to take this up. That is fair: rights and respon- sibilities go together.' The state will be the sole judge of whether an offer is suitable. This is a proposal for conscription.

Conscription in peacetime is within the powers of the state in a free country, but it is something which must be undertaken with caution, and only for compelling rea- sons. Above all, there must be a clearly defined right of conscientious objection, to be judged by authorities independent of the enforcing agency. Apart from any question of freedom or moral justification, conscrip- tion in a free society is unenforceable with- out this safety valve. That is as it should be.

If Tony Blair means this, even in the limited form of the good cause provisions in the existing legislation in the Jobseek- ers' Act, he should say so, and so far he has not. What we hear instead is the moralist's easy assumption that 'this may hurt, but it's for your own good'. In his Big issue interview, in a passage with the same crucial ambiguity about whether it applies to the long-term unemployed or only to the young, he said in a reply to a question about a proposal to remove benefits after six months: 'The Labour Party's policy is that people should be offered a range of options with obligation to take one. But they are high-quality options.'

This is a voice familiar for centuries. It is the patriarchal voice of the man who offers his daughter an arranged marriage. When she refuses it, he locks her up till she changes her mind, saying reproachful- ly, 'But it was a good match.' He does not understand that there are reasons why it may not be a good match for her which he is quite unable to judge. Similarly, women today may refuse a job out of a distrust of an employer which men cannot assess. This is one of their survival mechanisms, and they should not be denied it. Take, for example, the woman who said, 'He had a strange and odd effect on me. It's very hard to explain. It was the way he looked at me.' Tony Blair would have said she was failing in her responsibilities, but the man of whom she was speaking was Thomas Hamilton.

What Blair is proposing seems to be to extend to all benefits the sort of effective compulsion backed by benefit sanction at present involved in the youth training pro- gramme. He has shown no way of avoiding more cases like those of the asthmatic who was required to work as a painter, or the man who wanted to work with animals and was sent to work in an abattoir. Even if we get nothing worse than a garage mechanic sent to work as a hairdresser (or vice versa), it is questionable whether we are doing anything very useful. Even with the extreme degree of compulsion used on 16- to 17-year-olds, it has not worked. The proportion of the age group involved in youth training has fallen since 1989 from 21 per cent to 12 per cent. All that compulsion has achieved is the enlarging of the under- class, the opposite of what Blair wants. The proposed extension of this system of compulsion to single parents is as yet half- hearted. There is almost nothing about the constructive measures needed to enable single parents to work if they choose; those cost money and the new spending commit- ments may have ruled them out. Tony Blair mentions child care and the poverty trap created by housing benefit tapers, but there is nothing about any measure to alleviate them. He offers no welcome for Kenneth Clarke's child care disregard on Family Credit (announced in the 1993 Budget), or for his cheery remark that 'probably few single parents became pregnant after con- sulting their welfare rights officers'. Tony Blair does not yet propose to force single mothers to be available for work. Instead, he proposes 'a careers interview that would discuss job possibilities'. In the climate of Blair's other measures, is there any chance that single parents would take this as any- thing other than a threat?

This proposal completes a system in which the infliction of fear will be used as a substitute for spending money. Solutions to these questions lie in the creation of oppor- tunities. They do not lie in coercing people into taking them.

The author is a Liberal-Democrat spokesman in the House of Lords and Pro- fessor of History at King's College, London.

Previous page

Previous page