Pain or Hunger

By CLIFFORD COLLINS IT was my first week in the building. A twelve-year-old was kneeling on his pal's midriff, and with a raucous sense of enjoyment beating his head against the playground wall. " We're only playing, sir," he said as I passed. It was quite true, and I apologised privately for the interruption and made, the necessary mental adjustment. By this time, it was not a great adjustment to have to make; indeed, I was glad that we were still friends, the head-banger and I, for you can fall out with a lot of people in a week.

My corridor shift is on a Tuesday, and it was a wet October one, still in my first month. The corridors are sixty yards long, one on top of another, rubber on concrete, and on Tuesdays I walk them. The rubber makes the click and clatter of a thousand feet into, a gentle thunder, when at ten- thirty-five the milk whistle sounds for a general exodus. Five hundred boys leave seventeen classrooms, and make for the crates; five hundred silver caps are torn from five hundred half-pints. After a very summary drinking, the ushering out- side begins.

I seem to remember having taught the spelling rule, ' i ' before ' e ' except after ' c ', before break that morning, listing the exceptions, but here the technique is to allow none. 1 know it is wet, but there is a covered way round a square of grass on one side of the building. There is no shelter on the other side. A quarter of a mile of playing-field separates us from the railway lines and repair shops, chimneys, corrugated roofs, and shunting convalescent engines. All the same, the technique is to allow no exceptions, not even the washroom. And the seventeen classrooms, like those who teach in them, are having a rest. Today there is one excep- tion. The kids are forming a gangway outside, I am looking on behind locked doors. Hoisted up by the arms on two pairs of shoulders, Daly is being brought in.

I know Daly, for I have already kept him in after school, for spontaneous malice. Daly is tough, but unpopular among the toughs. He is handsome and not stupid, but quick-witted.

His face is a dirty angel's, though he has a wider range of expression; and he is an atheist (which is what Dad has told him to be). " It's all right for you," he said to me knowingly but truly, on one of my after-school reforming efforts, " You had a mother." While I was walking the lanes between the benches, Daly, with one or two others, was writing lines.

Someone mumbled, " It's all right if you're rich," meaning somehow, me. " I wonder what 'e is ? " the same voice said.

" 'Int," replied Daly, without stopping on his way through I must not talk when I am told not to talk,—"'im? 'E's as blue as Churchill." .

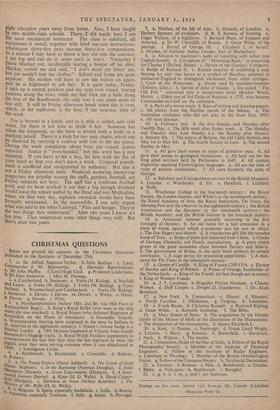

Daly is quite cold, and I am glad. Last week he put carbide in my inkwells, and I found a dead canary pinned on my blackboard. However, I must investigate. The culprit, I find, is Button, so I send for him while Daly is being revived. Button comes from the ex-Polish army camp in Heather Lane, where this sort of thing happens nightly. Button is big and dark, and he always wears a black suit to match. He has a slothful, easy disposition, and is quite manageable in class. " I was eight educative years away from home. Also, I have taught n two middle-class schools.. Thera, I did teach; here I am he most mechanical instructor. The class is subdued, all equipment is issued, together with brief staccato instructions; whereupon thirty-five pens execute thirty-five compositions. In a minute I may have to throw a boy out into the corridor, am big and can do it, some can't or won't. Yesterday I threw Mackay out, incidentally tearing a button off his shirt. Mackay cursed me and said, I don't mind yer hittin' me, but yer needn't tear me clothes." School and home are quite ¢eparate. His mother will have to sew the button on again, and he is frightened to ask her. It is quiet today, Friday. I take up a central position and my eyes rove round, tracing patterns along the rows, while my feet Rick me a little along the line of the floorboards, the only way I can stand more or less still. It will be Friday afternoon break when this is over, which, in the staffroom, is the best, if the weariest, time of the week.

Tea is brewed in a kettle, and to it milk is added, and cold water, for there is not time to drink it hot. Someone has taken the teaspoons, so the brew is stirred with a knife or a marking pencil. There is a rush for two easy chairs, which can be reserved by carrying a cushion with you to the tea queue. During the week complaints about boys are voiced, justice reported. Justice is " even-handed," but this word has a new meaning. If you have to' hit a boy, hit him with the flat of your hand so that you don't leave a mark. Corporal punish- ment is unofficial and unsupported by authority. But this is not a Friday afternoon issue. Weekend motoring (motor-car magazines are popular among the staff), gardens, football, are Friday subjects, not boys. The Staff has a syndicate football pool, and we have worked it out that a big enough dividend Would leave the school staffed by the Head and two Methodists, When, on that very day, eighteen contracts would have been formally terminated. In the meanwhile, I can only repeat What was said to me when I arrived, " Pain and hunger. They're the two, things they understand." After two years I know it's pot true. They understand some other things very well. But that's after two years.

Previous page

Previous page