Chess

By PHILIDOR

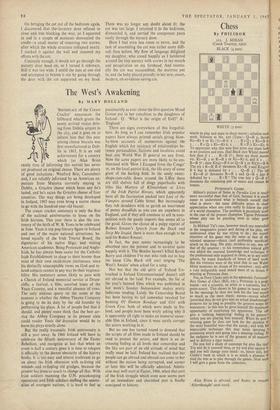

211. J. MIKAN (Czech Tourney, 1962)

BLACK (4 men)

WHITE (5 men) WHITE to play and mate in three moves ; solution next week. Solution to No. 210 (Tura) : Q—B 2, threat Kt—Kt 6 or Kt (7)—B 6. 1 . . . B x Q; 2 Kt—B 6.

. . . R x Q; 2 Kt—Kt 6. t. . . K x P; 2 Kt—Kt. 6. To appreciate why this won first prize one must look at set position and tries. Had Black (not White) moved first then if 1 . . . R—B 7? ; there are three mates, viz. Kt—K 3 or R—B 5 or Kt—Kt 6, and if 1 . . B—B 7? ; then Kt(4)—B 6 or Q—B 5 or Kt(7)—B 6. The try 1 R—K B 2? threatens Kt—K 3 and Kt(4)-- B 6 but is defeated by I . . . Q—R 3 1 The trY Kt—B 2? threatens R—B 5 and Q—B5 but is defeated by 1... BxR I The true key t Q—B 2! threatens the remaining pair of mates and cannot be beaten.

PETROSIAN'S GAMES

Milton's picture of Satan in Paradise Lost is much more successful than that of God, because it is much easier to understand what is beneath oneself than what is above : the same difficulty arises in chess appreciation when one tries really to follow the play of a world champion. The problem is peculiarly acute in the case of the present champion Tigran Petrosiaa, whose play can be puzzling even to other great masters.

In Mikhail Tal's case, however much one marvelled at the imaginative power and daring of his play, one understood what he was trying to do ; the central objective of his game was the same as that of the talented amateur—direct (and preferably sacrificial) attack on the king. His play, needless to say, was not that of the amateur ; to his tremendous natural gifts, was added the essential knowledge and technique of the professional only acquired in chess, as in any other sphere, by many hundreds of hours of hard work. But his victories were of the kind that in our Walter Mitty moments we dream of for ourselves : only after a very indigestible meal would most of us dream 01 winning as Petrosian does. For, as Peter Clarke says in his admirable Petrosian's Best Games of Chess (Bell, 25s.), Petrosian is a prag- matist : not a scientist, an artist or a romantic, but 0 point-scorer. This shows in his games in many ways, In the openings he does not look for the best moves so much as the most elastic moves—moves which (provided they do not give him an actual disadvantage) preserve for as long as possible the greatest scope for manoeuvre : in this way he gives himself the maximal opportunity of outplaying his opponents. This can give a 'nothing happening' feeling in his games-- unless you are playing him yourself. When he gets $ winning game he does not look for the quickest tr the most beautiful win—but the surest ; and with his impeccable technique this may mean ignoring promising attack and going into a winning ending. In the endgame he is one of the greatest of all masters) and in defence a tiger indeed. Do you feel a shade of contempt for play like this? Try and do it yourself then, or try and play against it and you will change your mind : or, better still, 1:4 Clarke's book in which it is as much a pleasure 10 read the text as to play through the games. Next vital' I will give a game from the collection.

Alan Brien is abroad, and hopes to resunl 'Afterthought' next week.

Previous page

Previous page