Larva and butterfly

Elizabeth Lowry

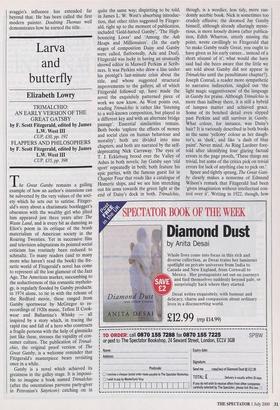

TRIMALCHIO: AN EARLY VERSION OF THE GREAT GATSBY by F. Scott Fitzgerald, edited by James L.W. West III CUP, £30, pp. 192 FLAPPERS AND PHILOSOPHERS by F. Scott Fitzgerald, edited by James L.W. West III CUP, £35, pp. 398 The Great Gatsby remains a galling example of how an author's intentions can be subverted by the very values of the soci- ety which he sets out to satirise. Fitzger- ald's story about a charismatic bootlegger's obsession with the wealthy girl who jilted him appeared just three years after The Waste Land, and is every bit as damning as Eliot's poem in its critique of the brash materialism of American society in the Roaring Twenties. Yet in successive film and television adaptations its pointed social criticism has routinely been reduced to schmaltz. To many readers (and to many more who haven't read the book) the fre- netic world of Fitzgerald's novel has come to represent all the lost glamour of the Jazz Age. The American market, succumbing to the seductiveness of this romantic mytholo- gy, is regularly flooded by Gatsby products: in 1974 alone, to tie in with the release of the Redford movie, these ranged from Gatsby sportswear by McGregor to re- recordings of 1920s music, Teflon II Cook- wear and Ballantine's Whisky — all inspired by a story which, in tracing the rapid rise and fall of a hero who constructs a fragile persona with the help of gimmicks just like these, stresses the vapidity of con- sumer culture. The publication of Trimal- chio, the original proof version of The Great Gatsby, is a welcome reminder that Fitzgerald's masterpiece bears revisiting once in a while.

Gatsby is a novel which achieved its greatness in the galley stage. It is impossi- ble to imagine a book named Trimalchio (after the ostentatious parvenu party-giver in Petronius's Satyricon) catching on in quite the same way; dispiriting to be told, in James L. W. West's absorbing introduc- tion, that other titles suggested by Fitzger- ald, right up to the moment of publication, included 'Gold-hatted Gatsby', 'The High- bouncing Lover' and 'Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires'. (In the early stages of composition Daisy and Gatsby were called, flatfootedly, Ada and Dud). Fitzgerald was lucky in having an unusually shrewd editor in Maxwell Perkins at Scrib- ners. It was Perkins who drew a line under his protégé's last-minute crisis about the title, and whose suggested structural improvements to the galleys, all of which Fitzgerald followed up, have made the novel the exquisitely patterned piece of work we now know. As West points out, reading Trimalchio is rather like 'listening to a well-known composition, but played in a different key and with an alternate bridge passage'. Essential similarities remain. Both books 'explore the effects of money and social class on human behaviour and morality'; both are divided into nine chapters, and both are narrated by the self- deprecating Nick Carraway. The eyes of T. J. Eckleburg brood over the Valley of Ashes in both novels; Jay Gatsby says 'old sport' repeatedly in both; both feature his epic parties, with the famous guest list in Chapter Four that reads like a catalogue of Homeric ships, and we see him stretching out his arms towards the green light at the end of Daisy's dock in both. Trimalchio, though, is a wordier, less tidy, more ran- domly acerbic book. Nick is sometimes too crudely effusive; the doomed Jay Gatsby himself, although already alluringly myste- rious, is more loosely drawn (after publica- tion, Edith Wharton, utterly missing the point, wrote cavillingly to Fitzgerald that `to make Gatsby really Great, you ought to have given us his early career... instead of a short résumé of it'; what would she have said had she been aware that the little we are told about Gatsby did not appear in Trimalchio until the penultimate chapter?). Joseph Conrad, a reader more sympathetic to narrative indirection, singled out 'the light magic suggestiveness' of the language in Gatsby for praise. Although Trimalchio is more than halfway there, it is still a hybrid of lumpen matter and achieved grace. Some of its botched detail even slipped past Perkins and still survives in Gatsby. What colour, for instance, was Daisy's hair? It is variously described in both books as the same 'yellowy' colour as her daugh- ter's, as 'dark', and like 'a dash of blue paint'. Never mind. As Ring Lardner fore- told after identifying four glaring factual errors in the page proofs, 'These things are trivial, but some of the critics pick on trivial errors for lack of anything else to pick on.'

Spare and tightly sprung, The Great Gats- by clearly makes a nonsense of Edmund Wilson's remark that Fitzgerald had been `given imagination without intellectual con- trol over it'. Writing in 1922, though, how was Wilson to know? At the time he had only the apprentice work to go by, among which was a collection of short stories called Flappers and Philosophers. All of these stories had been written for the mass- circulation 'slicks' in which Fitzgerald placed his exercises in popular fiction. The Cambridge reissue contains six previously uncollected magazine items in addition to the eight which made up the original vol- ume. The problem with Fitzgerald's short fiction is that the taste of the market for which it was written so obviously dictates its form. Readers of the 1920s were still not surfeited with 0. Henry the great Ameri- can tweaker of dénouements.

0. Henry's Complete Stories, each ending with a twist in the tail, were reprinted for a hungry public in 1927; Fitzgerald had to compete. The result is that these 14 pieces, many of which are narrated in the suave, commonplace smoking-room tone then preferred by the Saturday Evening Post and Smart Set, are further inflected by a dull predictability. Penniless Yanci Bowman pretends to fabulous wealth in order to ensnare an eligible bachelor, only to dis- cover that he has known the truth about her all along. Hemmick learns that the mis- placed one-cent piece that cost him his job as a bank clerk set another man, who picked it up from the pavement, on the road to fortune. Dalyrimple sticks uncom- plainingly to his badly paid post in the stockroom of a grocery store because he has a lucrative nightlife as a burglar, but is rewarded by his boss for being a model employee. And so on, and on. Fitzgerald was resolute that his weaker stories were `Positively not to be republished in any Form!', as he wrote on the tearsheets. The Cambridge edition, like any omnium gatherum worth its salt, has blithely ignored this warning.

Previous page

Previous page