Some lost worlds recaptured

Mary Hope

THAT LADY by Kate O'Brien

Virago, 13.95

WOMEN IN THE WALL by Julia O'Faolain

Virago, £3.95

NEVER NO MORE by Maura Laverty

Virago, £3.95

Virago have latterly been accused of scraping the barrel to find enough new neglected writers to fill their lists; but this spring they confused their critics by coming up with at least three Irish writers who deserve more than glancing attention. Two of them, Kate O'Brien and Maura Laverty, have for long been no more than names at the back of my head: titles and covers on parents' bookshelves, part of one's child- hood, like the novels of Elizabeth Taylor, familiar furnishings which, for some reason, were never actually read. Now, of course, one realises how short-sighted and snooty was one's adolescence. Not for nothing did half a million people buy, read 22 THE SPECTATOR 1 June 1985 and love That Lady; I just remember reading the posters for the film. Julia O'Faolain is, of course, still writing, better stuff now than this early historical novel, but Women in the Wall does stand as an ambitious and interesting oddity, with its glancing attention to female obsessive be- haviour and its wrestling match with the souls-and-bodies dichotomy which many a feminist writer, Catholic or not, eventually has to join. And reading Maura Laverty's skilfully meandering account of an Irish country girlhood is like sitting in the corner of the kitchen and listening to country gossip. Anecdote leads to anecdote; farce, tragedy and licentiousness jostle artfully without being classified by adult sensibility — a truly childlike, clear-eyed, unjudging view of an innocent vanished world.

That Lady first appeared at the end of the war, and one is tempted to see contem- porary concerns in this enormously long and psychologically detailed account of the interweaving of personal and political morality, a down-to-earth Catholic treat- ment of one woman's dealings with the truth of feelings: private expiations as opposed to political expediency. Set in 16th-century Spain, it is an account of Philip II's relationship with Ana de Men- doza, Princess of Eboli, the beautiful, one-eyed widow who has never been his mistress but whom he has always loved (mistaking possessiveness for love), and with whom he plays a self-teasing cat-and- mouse game for years, assuming that now she is old (36), they can enjoy a sinless intimacy. She falls in love with Antonio Perez, his secretary of state; another cour- tier, Escovedo, jealous, discovers their love and accuses her, in flagrante. She is beset by remorse and, suddenly, a real sense of the meaning of her own actions,

now answerable to herself and to God in ways in which she has never before been tested. Political intrigue, murder, violence, politics, swirl around the intimate story of her private moral battle, with herself, with Antonio and, above all, with Philip, whose jealousy and treachery stiffen her resolve to take her own decisions and receive punishment, and life imprisonment at the king's hands.

It is a vast, complicated and exceedingly skilfully plotted drama, combining the excitement of intense political discussion, personal moral conundrum, and the strug- gle to the death between straight noble Ana and the confused fanatical, God- and death-fearing king in whose breast is 'awareness day and night of the unwinking eye of God'. Philip is a figure who always fascinated Kate O'Brien, as her account of him in 'Farewell Spain' (also published by Virago) shows; but it is Ana who emerges as the extraordinarily interesting character: a truly 'good' woman, who is also intelli- gent, and morally enlightened. As she begins her affair with Perez, she realises, from the outset, that sin should have a meaning: 'the spirit was saying that the private life, however deprecatingly one chose to view it, must surely be about something more than the commonplace of any street or bed. There must still be a reason, Ana thought, for being oneself, and this is not it. Suffering perhaps, or conflict or faith or an argument or a test of some kind.' The rest of the book plays out all these things. Life is about being tested: a fact that Kate O'Brien knows and most movingly illustrates.

That everyone loves a martyr is one conclusion to be drawn from the success of That Lady, and it could also be the formula for Julia O'Faolain's much more rumbus-

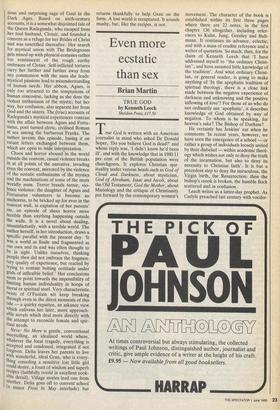

tious and surprising saga of Gaul in the Dark Ages. Based on sixth-century accounts, it is a somewhat disjointed tale of the Oueen Radegunda, who escaped from her foul husband, Clotair, and founded a convent as a refuge for her Brides of Christ and was sanctified thereafter. Her search for mystical union with The Bridegroom gets mixed up with physical ecstasies rather too reminiscent of the rough earthy embraces of Clotair. Self-inflicted tortures carry her further and further away from any communion with the nuns she leads: mystical passions lead to misunderstanding of human needs. Her abbess, Agnes, is only too attracted to the temptations of human concourse, lacking as she does the violent enthusiasm of the mystic; but her way, her confusion, also separate her from God and the sisters. The (true) accounts of Radegunda's mystical experiences contrast with the affair between Agnes and Fortu- natus, poet turned cleric, civilised Roman at sea among the barbarous Franks. The author invents this episode, basing it on extant letters exchanged between them, which are open to wide interpretation.

Chaos and horror abound in the world outside the convent, casual violence breaks In at all points of the narrative, invading even the convent, mirrored by the violence of the ecstatic enthusiasms of the mystics and the machinations of some of the more worldly nuns. Terror breeds terror, vio- lence violence: the daughter of Agnes and Fortunatus volunteers to become an anchoress, to be bricked up for ever in the convent wall, in expiation of her parents' sin, an episode of sheer horror more terrible than anything happening outside the walls. It is a novel about dealing, unsatisfactorily, with a terrible world. The author herself, in her introduction, draws a specific parallel with the present day: 'It was a world as fissile and fragmented as our own and its end wa.s often thought to be in sight. Unlike ourselves, thinking people then did not embrace the fragmen- tary quality of experience, but reacted by

trying to contain bolting certitude under grids of inflexible belief.' Her conclusions

seem to point towards the impossibility of limiting human individuality in hoops of moral or spiritual steel. Very characteristic twists of O'Faolain wit keep breaking through even in the direst moments of this tale — a quirky repartee, an askance view which enlivens her later, more approach- able novels which deal more directly with, the attempt to reconcile female and spir- itual needs.

Never No More is gentle, conventional storytelling, an idealised world where,

whatever the local tragedy, everything is accepted and condoned, integrated if not forgiven. Delia leaves her parents to live with wonderful, ideal Gran, who is every- thing consoling a sensitive lost little girl could desire, a fount of wisdom and superb

recipes (faithfully retold in excellent cook- able detail). Village stories lead one from another. Delia goes off to convent school (a minor Frost in May interlude) but

returns thankfully to help Gran on the farm. A lost world is recaptured. It sounds mushy, but, like the recipes, is not.

Previous page

Previous page