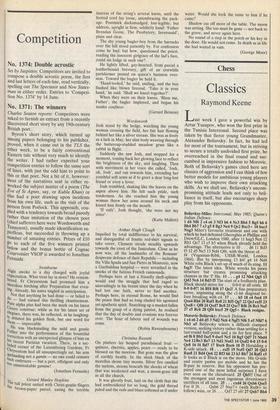

No. 1371: The winners Charles Seaton reports: Competitors were asked

to furnish an extract from a recently discovered short story by any 19th-century British poet.

Byron's short story, which turned up among papers belonging to his publisher, proved, when it came out in the TLS the other week, to be a fairly conventional Eastern tale without very much to identify the writer. I had rather expected your competition entries to follow the same sort of lines, with just the odd hint to point to this or that poet. Not a bit of it, however: most of the narratives sent in either re- worked the subject matter of a poem (The Eve of St Agnes, say, or Kubla Khan) or else had a poet drawing upon incidents from his own life, such as the visit of the Person from Porlock. This approach, cou- pled with a tendency towards broad parody rather than imitation of the chosen poet (chief sufferers here were Wordsworth and Tennyson), usually made identification su- Perflous, but succeeded in throwing up a number of amusing entries. Prizes of £10 80 to each of the five winners printed below and the bonus bottle of Cognac Courvoisier VSOP is awarded to Jonathan

Fernside. Swinburne

Algie awoke to a day charged with joyful expectation. What treat lay in store? He remem- bered. Fr Chrysostom had promised him a Merciless birching after Preparation that even- ing. Already, his nates tingled in anticipation.

Not that anything he had done — or failed to

(in — had earned this thrilling chastisement. Pure alpha plus had been the mark on his latest Cicero construe; while as for his latest set of elegiacs, there was, he reflected, as he laughing- ly his golden flesh, but one word for them — impeccable.

He was blackmailing the mild and gentle

Father into the performance of this bountiful correction with an unexpected glimpse of him on his recent Parisian vacation. There, in a sec- luded corner of the Luxembourg Gardens, Fr Chrysostom had all unsuspectingly sat, his arm garlanding not a gamin — no one could censure such embraces — but a pert, effulgent and only toe unmistakable gamine!

(Jonathan Fernside) Gerard Manley Hopkins

The tall priest untied with Christ-gentle-ngers tile brown-paper parcel, easing the tefirrible

instress of the string's several knots, until the fretted cord lay loose, unembracing the pack- age. Postmark darksmudged, lost-legible; but address, upright in firm, soldierly hand: 'Father Brendan Gorse, The Presbytery, Inversnaid', plain and clear.

The shy young bugler-boy from the barracks over the hill stood patiently by. For confession come he had; but how, questioned the priest, reading the innocent girlgrace of the lad's face, could sin lodge in such one?

He lightly lifted, gay-hearted, from parcel a leatherbound breviary, gift of an erstwhile parishioner posted on queen's business over- seas. Toward the bugler he held it.

'Hand-tooled,' he said, smiling, and the boy flushed like blown firecoal. 'Take it in your hand,' he said. 'Shall we kneel together?'

When they were on their knees, 'Bless me, Father', the bugler implored, and began his tender confiteor.

(Gerard Benson) Wordsworth Josh stood by the hedge, watching the young woman crossing the field, her fair hair flowing behind her like a silver stream. She was as lively as a lark in May, her slim body weaving through the buttercup-studded meadow grass like a rabbit in flight.

Suddenly she saw Josh, and stopped for a moment, tossing back her glowing face to reflect the brightness of the sky, and laughing. Then with merriment in her voice she called, 'Josh, oh, Josh', and ran towards him, extending her youthful soft arms as if to greet a dear long-lost friend or even a lover.

Josh trembled, shaking like the leaves on the aspen above him. He felt such pride, such tenderness. As she reached him the young woman threw her arms around his neck and kissed him firmly on the mouth.

'If only', Josh thought, 'she were not my sister'.

(Katie Mallett) Arthur Hugh Clough Impelled by total indifference to his survival, and disregardful of frantic red-shirt signals to take cover, Clement strode steadily upwards towards the crest of the Janiculum. Close as he now was, all the landmarks of the Romans' desperate defence of their Republic — including the Villa Spada and San Pietro in Montorio, now a Garibaldian hospital — were wreathed in the smoke of the furious French cannonade.

Perhaps here at last a friendly shell-splinter would end the struggle that had raged so unavailingly in his breast since the day when he had lost one faith, never to find another. Perhaps here, in eternal Rome, he would find the peace that had so long eluded his agonised yet apathetic spirit. Snatching up a musket fallen from the grasp of a dying patriot, he realised that the day of doubts and evasions was forever over. The hour of labour and of wounds was come.

(Robin Ravensbourne) Christina Rossetti

On platters lay heaped paradisiacal fruit quinces, cherries, apples, pears — ready to be blessed on the morrow. But gone was the glow of earthly health. In the sleek black of the morellos. shone tiny moons. Silver fire candied the melons, moons beneath the shocks of wheat that was weakened and wan, a moon-grass still as all the church.

It was ghostly fruit, laid on the cloth that she had embroidered for so long, the gold thread paled and the reds and blues softened as if under water. Would she look the same to him if he came?

Shadow cut off more of the table. The moon was setting. She too must be gone — not back to the grave, and never again here.

No sound of a step in the porch or his key in the door, He would not come. In death as in life she had waited in vain.

(George Moor)

Previous page

Previous page