TIME PLEASE, GENTLEMEN

Who killed off the gentleman? Ewa Lewis says

that she has received a buffeting from all sides.

But in the end, it was the ladies wot did it

GENTILITY is in the news. A whole book has been published in favour of it (Gentili- ty Recalled, edited by Digby Anderson, published by the Social Affairs Unit). But in so far as the male version is concerned, one should never assume that to be called a gentleman is an outright compliment. Flaubert knew that the rank was ambiva- lent. Of the Englishman (and thus the core species) he noted, 'A peculiar brutality pierces his manner, the result of a com- mand of half-easy things such as the man- agement of thoroughbred horses and loose women.'

After the second world war, the cult of gentlemanliness began to die out and nowadays no one could say that it contin- ues to exist as a station in life. The Victori- ans needed an imperial class and the whole essence of a gentleman was rooted in inequality. People readily and instinc- tively differentiated then between men who were gentlemen and those who were not. Today, such a judgment would imme- diately be undermined by accusations of sexism or elitism. Though inequality was the key, the ruling class was (contrary to socialist conviction) never a closed caste. There was constant recruitment into it, which is why public schools flourished. The entry into this ruling class carried moral overtones and assumed certain stan- dards of behaviour.

But what was a gentleman? One reason why the idea was so widely accepted in British society was that no one was really sure. The quality of gentlemanliness was beyond analysis. The status implied a stan- dard of conduct which mutated with the years and yet which was understood at any given time by all but the outright parvenu. Chaucer's `parfit gentil knyght' was some- what different from the 17th-century Lord Chesterfield, who said of women: 'A man of sense only trifles with them, humours and flatters them but never consults them or trusts them in serious matters.' Jane Austen thought that sociability and con- sideration to others were paramount, and considered vanity the giveaway sign of a 'There seems to be a change of heart. Only yesterday he was considering euthanasia.' non-gent. She would have abhorred the preening, moisturised male faces staring out from the pages of that great journalistic misnomer GQ, which apparently is short for the Gentleman's Quarterly.

A gentleman had to possess a constella- tion of moral qualities that distinguished him from the mob. Among these were gen- erosity, the ability to accept and exercise leadership and the habit of fulfilling obliga- tions towards those who depended on him. Today, the idea of responsibility implies having power over someone and that alone is considered by many young men and women to be rather distasteful.

Money was an essential accompaniment to being a gentleman. A real one would have preferred to have gone short rather than be seen to count his change and would never, ever have boasted about what anything cost. Such qualities are, of course, subconscious. A gentleman never says he is one. Young men were once advised to wear their status as naturally and unfussily as they might a watch. Or, in the more colour- ful words of Lord Chesterfield teaching his son gentlemanly ways, 'Don't pull it out just to show you have one.'

The Victorians had lengthy discussions about what it meant to be a gentleman, and defined four basic types — the Officer, the Christian, the Scholar and the Sportsman. The inclusion of Christianity here might strike us as old-fashioned and prissy, but gentlemanliness was also a secular version of the basic recommendations of religion and served to underline the wide social acceptance of Christian mores.

But the most vital gentlemanly quality which has remained a constant over the years was courtesy towards — verging on idealisation of — women. The old-style gentlemanly ideal of the female was rooted in courtly love and yearning for Goethe's 'Eternal Feminine'. He was her knight, she was his queen. There was something rever- ent as well as sexual about it — a far cry from the hard-nosed nuptial agreements of today. A gentleman was, of course, scrupu- lous in his avoidance of any behaviour which might count as compromising towards a lady. In the officers' mess, the Victorian gentleman was forbidden even to mention a lady's name — a lesson, per- haps, for Captain Hewitt.

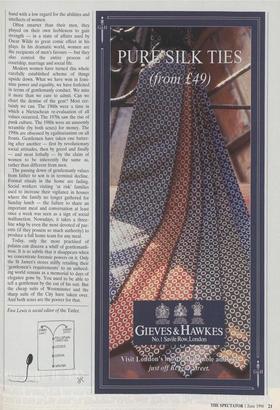

In return, a gentleman could expect that, like Princess Flavia in The Prisoner of Zenda, women 'knew their duty and acqui- esced'. Balzac saw woman as 'a slave one must be able to put upon a throne'. For women to merit this mixture of misogyny and devotion, they had to possess the virtues of gentleness, obedience and, above all, purity. It is astonishing to our coars- ened sensibilities to discover how long this ideal persisted and how unquestioned it was by the vast majority of middle-class females. Pre-1960s women were largely economically dependent on men and it was certainly more comfortable for them to deny that courtliness often went hand in hand with a low regard for the abilities and intellects of women. Often smarter than their men, they played on their own feebleness to gain strength — in a state of affairs used by Oscar Wilde to great comic effect in his plays. In his dramatic world, women are the recipients of men's favours — but they also control the entire process of courtship, marriage and social life. Modern women have turned this whole carefully established scheme of things upside down. What we have won in femi- nine power and equality, we have forfeited in terms of gentlemanly conduct. We miss it more than we care to admit. Can we chart the demise of the gent? Most cer- tainly we can. The 1960s were a time in which a Nietzschean re-evaluation of all values occurred. The 1970s saw the rise of punk culture. The 1980s were an unseemly scramble (by both sexes) for money. The 1990s are obsessed by egalitarianism on all fronts. Gentlemen have taken one batter- ing after another — first by revolutionary social attitudes, then by greed and finally — and most lethally — by the claim of women to be inherently the same as, rather than different from men. The passing down of gentlemanly values from father to son is in terminal decline. Formal rituals in the home are fading. Social workers visiting 'at risk' families used to increase their vigilance in houses where the family no longer gathered for Sunday lunch — the failure to share an important meal and conversation at least once a week was seen as a sign of social malfunction. Nowadays, it takes a three- line whip by even the most devoted of par- ents (if they possess so much authority) to produce a full home team for any meal. Today, only the most practised of palates can discern a whiff of gentlemanli- ness. It is so subtle that it disappears when we concentrate forensic powers on it. Only the St James's stores stiffly retailing their 'gentlemen's requirements' to an unheed- ing world remain as a memorial to days of elegance gone by. You used to be able to tell a gentleman by the cut of his suit. But the cheap suits of Westminster and the sharp suits of the City have taken over. And both sexes are the poorer for that.

Ewa Lewis is social editor of the Tatler.

Previous page

Previous page