Ancient & modern

THOSE who normally enjoy games often feel nothing but distaste for monstrous international foulathons such as Formula One racing and the impending World Cup. Many ancients felt the same about the Olympic Games.

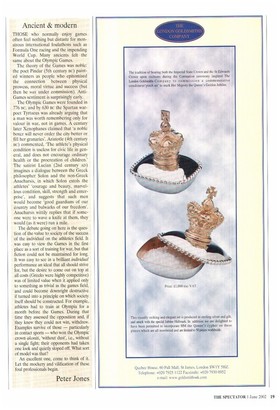

The theory of the Games was noble: the poet Pindar (5th century tic) painted winners as people who epitomised the connection between physical prowess, moral virtue and success (but then he was under commission). AntiGames sentiment is surprisingly early.

The Olympic Games were founded in 776 EC, and by 630 Bc the Spartan warpoet Tyrtaeus was already arguing that a man was worth remembering only for valour in war, not in games. A century later Xenophanes claimed that 'a noble boxer will never order the city better or fill her granaries'. Aristotle (4th century BO commented, 'The athlete's physical condition is useless for civic life in general, and does not encourage ordinary health or the procreation of children.' The satirist Lucian (2nd century AD) imagines a dialogue between the Greek philosopher Solon and the non-Greek Anacharsis, in which Solon extols the athletes' courage and beauty, marvellous condition, skill, strength and enterprise', and suggests that such men would become 'good guardians of our country and bulwarks of our freedom'. Anacharsis wittily replies that if someone were to wave a knife at them, they would (as it were) run a mile.

The debate going on here is the question of the value to society of the success of the individual on the athletics field. It was easy to view the Games in the first place as a sort of training for war, but that fiction could not be maintained for long. It was easy to see in a brilliant individual performance an ideal that all should strive for, but the desire to come out on top at all costs (Greeks were highly competitive) was of limited value when it applied only to something as trivial as the games field, and could become downright destructive if turned into a principle on which society itself should be constructed. For example, athletes had to train at Olympia for a month before the Games. During that time they assessed the opposition and, if they knew they could not win, withdrew. Examples survive of those — particularly in contact sports — who won the Olympic crown akoniti, 'without dust', i.e., without a single fight; their opponents had taken one look and quietly sloped off. What sort of model was that?

An excellent one, come to think of it. Let the mockery and vilification of these foul professionals begin.

Peter Jones

Previous page

Previous page