THANK YOU, MAAM

We rejoice in the renewed appreciation of the Queen by her subjects, and give thanks for her 50 years upon the throne. She deserves every manifestation of popular devotion heaped upon her. In an age of often meretricious politicians, she stands for the more durable qualities of duty, fidelity, service and self-control.

But it would be a serious error to suppose that her legitimacy depends on her popularity. We respect her precisely because she does not try to ingratiate herself with us. She is extraordinarily willing to suppress her private inclinations: on Monday, she is giving over the garden of Buckingham Palace to a concert which cannot accord with her own tastes. But she remains, in an admirably steely way, her own person, incapable of stooping to the maty devices that might have tempted a less formidable personality.

We mean it as a compliment when we say that she is part of the furniture; part of the familiar frame which has helped to lend stability and continuity to an otherwise rather changeable half-century. Let dictators worry about whether they retain their place in the hearts of the people. Part of the point of a constitutional monarch, ruling over a free people, is that we are at liberty to like her or not as we please, or to ignore her. Our political passions are directed into the strife between political parties, while our idea of liberty has long involved the right to be as rude as we please about those of exalted social position, including the Queen and her family.

In some ways she has become, during her reign, a more isolated figure. The hereditary nobility no longer counts, except in some localities, for very much. It has tended, with few exceptions, to withdraw from any very conspicuous public role. The present government has thrown most of the hereditary peers out of the House of Lords, without having the faintest idea how to devise another principle on which to select the members of that chamber without making it either unduly subservient, or else an unwarranted challenge to the democratic standing of the Commons. The Queen no longer stands at the pinnacle of a constitution in which the principle of heredity is embodied in hundreds of legislators. We do not know whether she repines at this change, but the fact that we do not know is one reason why her own position has been so little affected. For her, there can be no retreat into a purely private life, or into the limited role of a local landowner, but she knows how to keep any party-political thoughts she may have entirely private. This ability to remain above politics is so strong that we have come to take it almost for granted. In a curious and unintended way, it is a rather democratic characteristic, for a great many of her subjects are either repelled by adversarial politics, or regard it as at best a necessary evil. Many are the people who can see in the Queen a woman who, like them, regards horse-racing and her own dogs with more evident affection and excitement than she regards politics. In that sense, she is one of us, rather than one of the motley crew who push themselves forward in the battle for office. She does not need to push, which is, of course, one of the great justifications for privilege. It relieves those born to it of the warping effects that the struggle to gain power within one generation is almost bound to have. Her family have been losing power for many generations now, and for a long time have done so with good grace.

Those of us of a romantic frame of mind may regret this decline, but it is also a very impressive demonstration of the Queen's ability to adapt to new times. She is a pragmatist, who in the British way can combine tradition with innovation. There are no futile gestures, giving away prerogatives which she has no need to surrender, but nor is there an undignified clinging to the past. Changes and upheavals, embarrassments and disasters occur, as sooner or later they do in every life, yet the Queen continues with exemplary calmness on her course. From time to time a hysterical media demand that she fly a flag at half mast, or pay more tax, or kiss Prince Charles. She accommodates their wishes, but imperturbably.

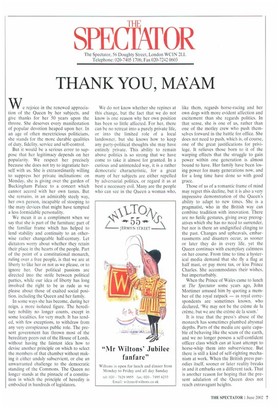

When the Prince of Wales came to lunch at The Spectator some years ago, John Mortimer amused him by quoting a member of the royal ratpack — as royal correspondents are sometimes known, who declared, We may not be the creme de la crème, but we are the creme de la scum.'

It is true that the press's abuse of the monarch has sometimes plumbed abysmal depths. Parts of the media are quite capable of behaving like the scum of the earth, and we no longer possess a self-confident officer class which can at least attempt to horse-whip them into subservience. But there is still a kind of self-righting mechanism at work. When the British press parodies itself, sooner or later reality breaks in and it embarks on a different tack. That is another reason for hoping that the present adulation of the Queen does not reach extravagant heights.

Previous page

Previous page