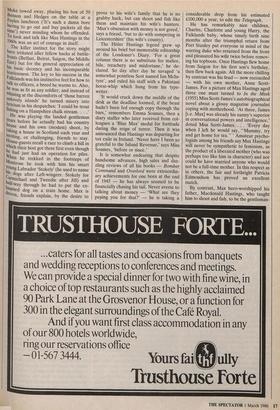

THE BLUE MAX

Outsiders: a profile of Max Hastings,

the wildest man ever to edit the Daily Telegraph

WHEN Queen magazine ran a feature on The Most Hated Man in Fleet Street The Editor' in 1969, one of the anonymous profilists was young Max Hastings, then the latest enfant terrible to be recruited by Charles Wintour of the Evening Standard. Wintour's fine art of rule by memo, wrote Hastings, could be withering, e.g. the day the writer had asked to be sent to Israel: `Dear You are the fifth (and least qual- ified) person who has today asked to go to the Middle East. James Cameron is air- borne for Israel. . . I will bear in mind your request for an exciting assignment, but they do not grow on trees to be plucked by hungry young mouths. Yours ever, Charles.'

This craving for exciting assignments, preferably battlefronts, did not wane. Fif- teen years later, Hastings was straining at the leash the day the Task Force was set up. The hacks that were going, he expost- ulated, wouldn't know a war if it bit them on the leg. Couldn't the paper intercede with Downing Street on his behalf?

`I wandered down the road. It stretched empty ahead, the cathedral clearly visible perhaps half a mile away. It was simply too good a chance to miss. . .

Thus in his own words on 14 June 1982 did Max Macdonald Hastings, aged 37, stride into the Upland Goose pub in Port Stanley in civvies with his arms raised: typical Max. As an impulse it was both courageous and entirely in character. It ensured his perpetual celebrity. It will now vouch him a welcome among a readership for whom the first man in Port Stanley has greater worth than any reporter, however gifted his despatches.

The overgrown schoolboy look is a blessing to caricaturists and this is what is so cheering about Max Hastings: he Is unmistakable, unique, a genuine young eccentric long before the current vogue for the breed. It was something to do with being six foot five and gangling, with a lock of lank hair over the forehead and a voice with no volume control. He booms. The huge feet were a damn bore: 'Have to have these shoes made at Lobb's.' He makes ceilings seem too low, chair legs too short; in any gathering he is certain of his opinions (he has never been heard to say, `I'm not sure. . .') and never in repose. The foot jigs, he is always about to leave. It was the unco-ordinated limbs in youth that made him useless at team sports, which is principally why he hated Charter' house. 'No day is too short to kick an Old Carthusian when he's down,' he once began a story. Failure at sport made him take up individual challenges. He had to join the Paras, tackle the Cresta Run.

He threw up his Exhibition at University College, Oxford after one year, pawing the ground to get at Fleet Street. He thought he could manage without the history de- gree and as events have confirmed, he was right. Doors opened fast, starting with the Londoner's Diary at £30 a week. `Do take your feet off the desk. We try not to look like caricature journalists round here,' drawled Roger Berthoud, the languid diary editor of the time. Berthoud and his staff were almost exclusively Old Etonians, so ragging Hastings became a pastime, ostentatiously wearing their OD ties and using school slang. These signs of boyish camaraderie were not lost on Hast- ings: his elder son is going to Eton. But there was no feeling of dislike; rather he was marvelled at: the way he crashed about like a clumsy buffoon, Hell s Bellsing (his favourite expletive) about having his absurdly inappropriate Mint" Moke towed away, placing his box of 50 Benson and Hedges on the table at a Foyles luncheon (`It's such a damn bore having to go out and buy packets all the time') never minding whom he offended. To look and talk like Max Hastings in the 1960s was an act of courage in itself. The killer instinct for the story might have irritated idler fellow hacks at battle- fronts (Belfast, Beirut, Saigon, the Middle East) but for the general appreciation of his basic decency and his incomparable fearlessness. The key to his success in the Falklands was his instinctive feel for how to talk to officers, a breed he warms to. Also, he was as fit as any soldier, and instead of Whining at the discomforts of 'those barren unlovely islands' he turned misery into lYricism in his despatches: 'I could be trout fishing on a Hampshire chalk stream. . . He was playing the landed gentleman Years before he actually had his country house and his own (modest) shoot, by taking a house in Scotland each year and inviting, or challenging, friends to stay. House-guests recall a race to climb a hill in which their host got there first even though he had just had an operation for piles.

Montrose he trekked in the footsteps of montrose he took with him his smart Young Labrador 'Stokely' (he used to name his dogs after Left-wingers: Stokely for Carmichael and Tweedie after Jill) and halfway through he had to put the ex- eausted dog on a train home. Max is driven, friends explain, by the desire to prove to his wife's family that he is no grubby hack, but can shoot and fish like them and maintain his wife's hunters. 'Max's obsession with money is not greed,' says a friend, 'but to do with competing in Leicestershire' (his wife's county).

The Hitler Hastings legend grew up around his brief but memorable editorship of the Londoner's Diary. 'For a great column there is no substitute for malice, bile, treachery and misfortune,' he de- clared. So day after day he savaged 'a somewhat pointless Scot named Ian McIn- tyre', and ruled his staff with a Pakistani horse-whip which hung from his type- writer.

`It would crack down the middle of the desk as the deadline loomed, if the beast hadn't been fed enough copy through the bars,' remembers Emma Soames, then a diary staffer who later received from col- leagues a 'Blue Max' medal for fortitude during the reign of terror. Then it was announced that Hastings was departing for tax exile in Ireland. 'Never have I been so grateful to the Inland Revenue,' says Miss Soames, 'before or since.'

It is somewhat endearing that despite handsome advances, high sales and daz- zling reviews of all his books — Bomber Command and Overlord were extraordin- ary achievements for one born at the end of 1945 — he has always seemed to be financially chasing his tail. Never averse to talking about money — 'What are they paying you for that?' — he is taking a considerable drop from his estimated £100,000 a year, to edit the Telegraph.

He has remarkably nice children, Charles, Charlotte and young Harry, the Falklands baby, whose timely birth nine months after the triumphal return from Port Stanley put everyone in mind of the warring duke who returned from the front and pleasured his wife twice before remov- ing his topboots. Once Hastings flew home from Saigon for his first son's birthday, then flew back again. All the more chilling by contrast was his feud — now reconciled -- with his own mother, Anne Scott- James. For a picture of Max Hastings aged three one must turned to In the Mink (1955) Miss Scott-James's autobiographical novel about a glossy magazine journalist coping with motherhood. 'At three, James [i.e. Max] was already his nanny's superior in conversational powers and intelligence,' doted Miss Scott-James. . . . 'Every day when I left he would say, "Mummy, try and get home for tea." ' Amateur psycho- logists among his friends say Max Hastings will never be sympathetic to feminism, as the product of a liberated mother (who was perhaps too like him in character) and nor could he have married anyone who would not be a full-time mother. In this respect as in others, the fair and forthright Patricia Edmondson has proved an excellent match.

By contrast, Max hero-worshipped his father, Macdonald Hastings, who taught him to shoot and fish, to be the gentleman- journalist, the soldier-scholar and the pat- ron of Wheeler's restaurant.

Perhaps Max is a romantic. He remains loyal to several striking women who swear that the gangling schoolboy's pursuit of them was hopelessly platonic; even, in one case, after a four-week holiday in Greece, as he never seemed to mind telling people. Despite the Lobb's shoes and the Havana cigars there is something quite un-grand and un-pompous which centres on his devotion even to humdrum journalism. Back from the Falklands he would write on anything required: dotty vicars, the price of spectacles, whither the GLC. His output is prolific. 'Most journalists make far too much fuss over 1500 words a week. Bron Waugh and I prove you can write 15,000 without straining yourself too much.' Tele- graph slackers please note.

The Telegraph now looks like his natural home, though he is far from a saloon-bar, shires or Thatcherite Tory, being temper- amentally anti-government. At his most caricaturable, taking Fortnum's hampers to the Biafra war (`The Ibo may be starving but MH certainly isn't going to') his chief motive is to tease the Left. The only reason he never found a Telegraph home before was that they did not go in for star reporters; nor for direct-control, gimlet- eyed, personal-stamp editors in the Charles Wintour mould. But they have one now.

Previous page

Previous page