Spring Books (II)

The great American disaster

Jan Morris

The New Golden Land Hugh Honour (Allen Lane £12.50) The American Indians Dean Snow (Thames and Hudson £6.50) One must not, of course, be beastly to the bicentennialists. The Americans are grown up now, though, and must know as well as anyone that this is hardly the best of all anniversaries for the best of all possible republics. I can see that '1776: Record of a Failure' might hardly be a suitable title for the great jamboree, but still it does no harm to recognise that in many respects the story of the United States is a story of broken hopes and disillusionment. 'Great unerring Nature once seems wrong,' wrote John Keats of America, and the Founding Fathers would be sad to know how many modern immigrants to the Great Republic, sampling its particular version of the pursuit of happiness, pine for the discredited systems and threadbare traditions of the Old World. America certainly has not flopped ('bombed', as they prefer to say on Broadway), but I sometimes think she is

lucky to get quite so many curtain-calls. Especially as mixed notices were her fate

from the start. In the early days of western

discovery, as Hugh Honour tells us in The New Golden Land, the idea of America was

inextricably confused with legend, fiction, wishful thinking and contradictory hearsay. It was the Golden Land, it was the Cannibal Continent, it was the classical world reani mated, it was a savage, unwholesome place, where nothing grew as healthily as it did in the Old World--the tapir, wrote the Comte de Buffon, was an absurd substitute for the elephant, the llama was an inferior camel, the puma was no lion, and the only animal which grew larger than it did in Europe was, very properly, the pig.

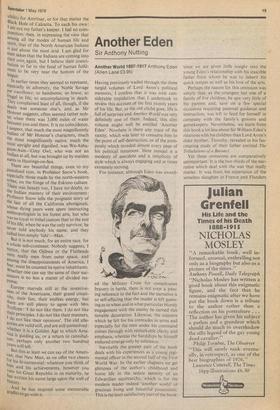

From those days to these, Europe has never been able to make up its mind about the place, whether it is decadent or resurgent, enviable or pitiable, to be admired or loathed. Mr Honour's learned and enthralling book is a sort of catalogue raisonne of these responses. It apparently is a byproduct of a bicentennial exhibition he has mounted at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, but it goes far beyond the reputation of the United States, and deals with America as a whole, America as a rumour, as a travellers' tale, almost as an abstraction. Mr Honour starts with Columbus and ends with David Hockney, and between this incongruous pair of bookends we see the pictures and hear the views of an amazing gallery of observers—explorers and conquistadores, missionaries and settlers, painters as varied as Blake, Degas and Mondrian, writers from Dickens and Chateaubriand to Rupert Brooke, who called the United States El Cuspidadoro, or Karl-May, whose American images of racial pride and purity were Hitler's favourite reading.

They express, between them, astonishment, bewilderment, horror, respect, contempt, envy, gratitude and detestation. The one emotion that is noticeably lacking from the anthology is plain disappointment. Revulsion often, disappointment seldom, and this is odd, for it seems to me that North America is far more a disappointing than a repellent place. Take its landscapes, for a start. Nearly all the exotica in Mr Honour's collection come from South America, and it was the lush and sinister world of Brazil, Mexico and Peru which stamped its images, of snow-mountain and humid forest, so vividly upon the European mind. The enormous slab of North America never conjured the same fancies of myth and symbolism, at least until the invention of the Wild West, and with reason: for on the whole, with the obvious exception of Australia, mile for mile it is the most tedious land on earth.

Consider it, that half a continent, Gulf of Mexico to Hudson Bay—seven million square miles, of which, I would hazard a guess, 90 per cent scarcely warrants a second glance. Half of it is covered with interminable conifers, much more consists of endless prairie: when something interesting does occur, it goes on and on and on. There is no proportion to it, no tact. The scale is all wrong. An hour of Arizona cacti is quite enough, a day of New England autumn tints gives us the message, and the train journey through the Rockies would be perfectly tolerable, for my own tastes, if they could cut it by three-quarters.

Even the Scenic Wonders, when you reach them at last, are short on magic, if on nothing else. The Grand Canyon is too Grand. The Great Lakes are much too Great. Yosemite is altogether too yosemite. The Golden Gate would be nothing without its bridge, and the Cascades would bg fine if they cut the trees down. I agree with the general consensus of Mr Honour's witnesses, that the one undeniably splendid natural spectacle of the United States is Niagara. Elsewhere monotony, or perhaps over-sell, is the hallmark of the landscape, and I am not in the least surprised to learn that if the settlers had come to Vermont at the end rather than at the beginning of their pioneering, they would never have bothered to settle it.

The North American indigene, too, seems to me, as homo sapiens goes, distinctly anticlimactic. The pioneers crossed a continent twice as big as Europe,and all they met were Red Indians! To the south the Mayas, the Aztecs and the Incas built their tremendous artifacts, bore themselves like gods, undertook their prodigies of surgery and engineering, science and mysticism. To the north the Sioux and the Apache, the Navajo and the Cree built themselves—wigwams.

This is an unpopular view I know, the Americans having worked themselves into a regular neurosis of remorse about their treatment of the Indians. One can hardly drive a mile into the once wicked West without coming across some gallery of Indian arrow-heads, some memorial collection of beads and feather-work, some anthropological exhibition of root medicine or tribal therapy.

Professor Snow, then, with his scholarly monograph on the pre-history of the Ame rican Indians, is sure to find a grateful audience. These after all were the first, the pre-Columbians, the ante-Revolutionists, and the guilt of the Americans is supple mented nowadays by a sense of regret and admiration too, as if they are not altogether sure that Laughing Bear's way wasn't better after all. Professor Snow's very readable description of the original North Americans will comfortably confirm them in their selfreproach, and reassure them that they really have something to be guilty about.

My heart, though, is not buried at Wounded Knee, just as I accept no respon

sibility for Amritsar, or for that matter the Black Hole of Calcutta. To each his own: I am not my father's keeper. I feel no compunction, then, in expressing the view that among all the modes of human life and sPirit, that of the North American Indians is just about the most arid. I am glad for their sakes that the Indians are coming into their own. again, but I believe their contribution so far to the fund of human fulfil ,ment to be very near the bottom of the league.

In earlier times they seemed to represent, especially in adversity, the Noble Savage Par excellence, so handsome, so brave; so frugal in life, so uncomplaining in death. They complained least of all, though, if the death was someone else's, and, as Mr Honour suggests, often seemed rather nobler when there was 3,000 miles of water between you and them. It is no coincidence, I suspect, that much the most magnificently Indian of Mr Honour's characters, much the most magnificently native, much the most upright and dignified, was Wa-Ashaguon-Asin-LGrey Owl, who was not an Indian at all, but was brought up by maiden aunts in Hastings-on-Sea.

There are beautiful things, even to my jaundiced eyes, in Professor Snow's book, especially those made by the north-western, tribes, on the fringe of the Eskimo culture. There was beauty too, I have nodoubt, to the Indian mastery of their environment: Professor Snow tells the poignant story of the last of all the California aboriginals, Whose dying years were spent instructing anthropologists in his forest arts, but who was so loyal to tribal custom that to the end of his life, when he was the only survivor, he never told anybody his name, and they called him simply 'Ishi'—Man.

But it is not much, for an entire race, for a whole sub-continent. Nobody suggests, I notice, that the Ojibwa or the Flatheads Were really men from outer space, and fear, the disappointments of America, I 'ear, must be counted its native inhabitants. Whether one can say the same of their suc cessors is no less a matter of divided resPonse.

Europe marvels still at the inventiveness of the Americans, their grand creatiYitY, their fun, their endless energy, but there are still plenty to agree with Mrs Trollope: 'I do not like them. I do not like their principles. I do not like their manners, I do not like their opinions'. The old allegories are valid still, and are still unresolved : Whether it is a Golden Age to which America is guiding us, or a return to cannibal '5m, perhaps only another two hundred, Years will tell. But this at least we can say of the American, that New Man, as we offer two cheers for his bicentennial: whatever you think of him and his achievements, however you V, iew his Great Republic in its maturity, he

has written his name large upon the wall of history.

And he has inspired some memorable graffiti to go with it.

Previous page

Previous page