Sh

Duncan Fallowell Silence Shusaku Endo (Peter Owen E4.25) Mr Shusaku Endo is that rare and provoking animal, the Roman Catholic Japanese novelist. You haven't come across one either? And Silence, his third novel to be published in this country in an American translation, describes what happened to Christian missionaries in seventeenth-century Japan. Religion, history, and foreign' ers, all in one packet, very off-putting, agree, and this is not helped by Graham Greene's Churchillian seal of approval: 'one of the finest novels of our time'. Nothing is more calculated to get on the nerves than the spectacle of literary lions forming cabals of mutual admiration across the high. seas. But members of this trans-cultural hol polloi, when left to themselves, are occasionally almost as good as other people saY they are, which is what Mr Endo is. .1 haven't the feeblest idea whether Silence Is one of the greatest novels of our time. Probably I lack Graham Greene's capacity for hoovering up all the others. It is, howeverr a marvellous book.

Silence is not autobiographical, except in the psychological sense. Nor, as novels g°' is it subjective. Mr Endo is giving deer thought to the most basic problems of truth and how in exchanging it among ourselves we misconstruct its nature at every step. This is particularly true of the Jesuit Os" sionaries whose high reputation for education often undermines their self-vigilanee and in whom, as this novel elegantly demonstrates, conviction is frequently nothing more than the habitual stubbornness of narrow vision, identification with symbols' ignorance, idolatry and intolerance. Mr Endo's novel is personal in the sense that it forces a personal response from the faculties of the reader, not personal because he is taking a partisan line in the handling of truth. He has pulled back from the clatter of ideology to observe exactly what is going on—the growth of perversity. And when we do the same it becomes clear that the Buddhism of Japan is on most counts doing, better in its respect for the properties 01 truth than are the Jesuit Fathers whose greed for other people's souls is not seen a.s an attractive quality. The difficulty here Is that Mr Endo is a Roman Catholic himself, so that one is always on the look-out for an event which neatly turns the tables in favour of Papal dignity. But it never comes an.cl' wherever your theological preferences lie' this is a chastening experience. Perhaps more than Mr Endo intends, his 'hero', Father Rodrigues, is revealed as self-righteous fool whose steadfastness in

the face of torture, conventionally regarded as a wonderful allegiance to God, is shown oP for what it really is, the brutish grip of delusion. This would not matter much if Rodrigues' action did not involve the persecution and killing of converts, a universe away from the official Church teachings on the magnificence of martyrdom, the appalling death of wretched peasants seduced by the Jesuits' cheap promise of no taxes and boon harvests in the hereafter.

With the question of apostasy comes the climax, and precipitates all the uneasiness we have ever felt about the way such missionaries go about their business, what one of the Japanese authorities calls in a terrific Phrase 'the persistent love of an ugly woman'. They explain to Rodrigues that, if unchecked, Christian subversion would tear their country apart, that the Japanese have constructed their own paths to truth and that these things cannot be swopped around like baubles. Rodrigues refuses to apostasise and so more converts are executed. The Japanese explain that only the outward form of apostasy is required, that he is otherwise free to believe whatever he likes. A one-time hero of Rodrigues and now an apostate himself, Father Ferreira, visits him in his Nagasaki prison to explain that he must place his foot on the picture of Christ to prevent more peasants being killed. The Japanese continue to ply him with intelligent Buddhist remarks. He recalls the words of St Francis Xavier: 'The Japanese are the most intelligent people we have met so far.' Rodrigues immediately understands this to Mean that they speak with the voice of the devil himself. More killings. Then suddenly, after many reminders from Ferreira, he remembers Christ, no longer as a picture but as a truth, and hears these words: Trample! It was to be trampled on by men that I was born into this world. It was to Share men's pain that I carried my cross:* Rodrigues places his foot on the image of Christ and is saved, although quite the oPposite is inferred by Rome.

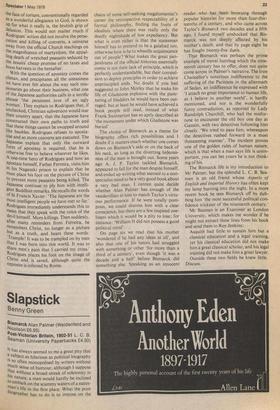

chaos of some self-seeking megalomaniac's career the retrospective respectability of a formal philosophy, finding the fruits of idealism where there was really only the deadly nightshade of low expediency. But what is even richer is that the statesman himself has to pretend to be a galahad too, otherwise how is he to wheedle acquiescence out of people? What makes the great panjandrums of the official histories essentially comic is not their lack of principle, which is perfectly understandable, but their compulsion to deploy principles in order to achieve unprincipled ends. No doubt if you had suggested to John M.orley that he make his life of Gladstone explosive with the puncturing of bladders he would have been outraged, but at least he would have achieved a book people still read, instead of what Frank Swinnerton has so aptly described as 'the monument under which Gladstone was buried'.

The choice of Bismarck as a theme for biography offers rich possibilities and I doubt if it matters much whether one comes down on Bismarck's side or on the back of his neck, so long as the diverting hideousness of the man is brought out. Some years ago A. J. P. Taylor tackled Bismarck, appeared to fall for the man despite himself, and ended up writing what seemed to a nonspecialist mind to be a very good book about a very bad man. I cannot quite decide whether Alan Palmer has enough of the vaudevillian in him to match Taylor's virtuoso performance. If he were totally pompous, we could dismiss him with a clear conscience, but there are a few inspired oneliners which it would be a pity to lose; for instance: 'William II did not possess a good political mind'.

On page six we read that his mother 'wondered if he had any ideas at all', and also that one of his tutors had struggled with something or other 'for more than a third of a century', even though 'it was a decade and a half' before Bismarck did something else. Speaking as an innocent reader who has been browsing through popular histories for more than four-thirteenths of a century, and who came across Taylor's Bismarck two decades and a fifth ago, I found myself unshocked that Bismarck was not deeply affected by his mother's death, and that by page eight he has fought twenty-five duels.

That Bismarck was perhaps the prime example of moral humbug which the nineteenth century has to offer, does not quite come across in Palmer's narrative. The Iron Chancellor's notorious indifference to the suffering of the Parisians in the aftermath of Sedan, an indifference he expressed with 'I attach no great importance to human life, as I believe in another world', is hardly mentioned, and nor is the wonderfully funny contradiction, as reported by Lady Randolph Churchill, who had the misfortune to encounter the old boy one day at Gastein, with two detectives following him closely. 'We tried to pass him, whereupon the detectives rushed forward in a most threatening manner'. The incident proves one of the golden rules of human nature, which is that when a man says life is unimportant, you can bet yours he is not thinking of his.

The Bismarck life is my introduction to Mr Palmer, but the splendid L. C. B. Seaman is an old friend whose Aspects of English and Imperial History has often kept my lamp burning into the night. In a more recent book he sees Bismarck off by dubbing him 'the most successful political confidence trickster of the nineteenth century.'

Mr Seaman is an Examiner at London University, which makes me wonder if he might not extract these lines from his book and send them to Roy Jenkins: Asquith had little to sustain him but a classical education and a legal training, yet his classical education did not make him a great classical scholar, and his legal training did not make him a great lawyer. Outside these two fields he knew little.

Discuss.

Previous page

Previous page