SNOU T §44

THE TROUGH

Martin Vander Weyer reports on

the increasing avarice of Britain's top businessmen, and suggests a few remedies

`LET'S SAY you work for Ford in Dagen- ham . . . and you're cut down to a four-day week — and it's not your fault, you've worked very hard . . . you're very compe- tent . . .' Jimmy Young's stand-in on Radio 2 is building up for a loaded question.'... And then you read that some director of a company suddenly gets a £120,000 pay rise that year, on top of, say, already receiving £300,000 or £400,000. Don't you find that slightly obscene?'

There have been two improbable stand- ins for Jimmy Young in recent memory. One of them was Neil Kinnock, to whom such a sentiment would come quite naturally. But this was the other one: Lord Archer, former deputy chairman of the Conser- vative Party, enunciating a British prejudice so deeply ingrained as to be found from time to time in virtually every part of the political spectrum.

But anyone who has had to negotiate other people's salaries and bonuses (as I did, in a previous City career) knows how quickly fairness can be set aside when there is serious money at stake. At the sniff of a package which will cover the country house and the school fees at a single stroke, oth- erwise moderate men will grasp like hungry beggars at the most meretricious of com- parisons and justifications.

The spring crop of corporate annual reports provides ample opportunity to see whether our captains of industry have taken any notice of the Prime Minister, or whether it has been another year of 'snouts in the trough', as Norman Willis of the TUC and numerous other pundits have put it. The small print of 'directors' emolu- ments' also provides substance for more reflective analysis of what really constitutes fairness in matters of top people's pay.

The daily press prefers simply to revel in anecdotal evidence for the snouts in the trough theory. Two years ago, a gleeful roasting was administered to the Governor of the Bank of England for accepting a 17 per cent rise after urging self-control on everyone else. An entire BT sales depart- ment rang the Sun to 'blast' an enormous `hike' (from £374,000 to £536,000) for Mr lain Vallance, chairman of British Tele- com, who was engaged at the time in mak- ing redundant large numbers of his lower-paid staff. Last year's villains were the post-privatisation water company heads, scooping up lavish helpings of com- parability with the private sector.

First in the stocks this year are building society bosses — not, you might think, men whose jobs are so challenging as to merit spectacular reward — with 14 per cent average pay rises despite a 10 per cent fall in profits; the rises have been denounced as 'outrageous and morally wrong' by the Building Societies Members Association. Elsewhere, the Daily Telegraph has weighed in with a column called Tough at the Top listing chairmen (of P & 0 and Standard Chartered Bank, for example) whose salaries have risen while their companies' earnings-per-share ratios — the best simple guide to management performance — have fallen. Barely a day goes by without news of yet another double-breasted plutocrat's colossal plateful of gravy.

All of this provokes a satisfying release of indignation, even if some of it is mis- chievous or misleading — bonus payments, for example, often relate to performance in the pre- ceding year, and some- times to several years at once. But the underly- ing statistical trends, less fun for tabloid sub- editors to play with, are in many ways more startling than the selec- tive headlines of indi- vidual excess.

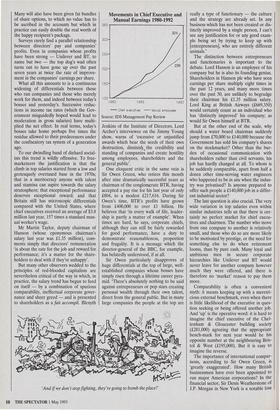

Manual workers' wages rose between 1980 and 1992 by about 140 per cent. But (according to research by Incomes Data Ser- vices, a firm of independent consultants on pay) chief executives' packages rose over the same period by 224 per cent, with the steepest divergence in the two lines on the graph occurring from 1989 onwards, after the recession began and corporate profits had begun to falter.

From the same source, a survey of 69 British companies in the FT-SE 100 index found the average industry captain pocket- ing an increase for 1991/92 of more than 15 per cent, twice the rate of inflation, to give him £463,220 of salary and bonus. Of the companies within the survey which had suf- fered a fall in earnings per share for the period in question, 88 per cent awarded their top men a healthy increase anyway. Many will also have been given fat bundles of share options, to which no value has to be ascribed in the accounts but which in practice can easily double the real worth of the happy recipient's package.

Surveys rarely find a parallel relationship between directors' pay and companies' profits. Even in companies whose profits have been strong — Unilever and BT, to name but two — the top dog's wad often turns out to have gone up over the past seven years at twice the rate of improve- ment in the companies' earnings per share.

What all this amounts to is a continuous widening of differentials between those who run companies and those who merely work for them, and indeed between today's bosses and yesterday's. Successive reduc- tions in income tax rates (which the Gov- ernment misguidedly hoped would lead to moderation in gross salaries) have multi plied the net effect. In real terms, today's bosses take home perhaps five times the residue allowed to their predecessors under the confiscatory tax system of a generation ago.

To our dwindling band of diehard social- ists this trend is wildly offensive. To free- marketeers the justification is that the climb in top salaries started from a low and grotesquely overtaxed base in the 1970s; that in a meritocracy anyone with talent and stamina can aspire towards the salary stratosphere; that exceptional performance deserves exceptional reward; and that Britain still has microscopic differentials compared with the United States, where chief executives received an average of $3.8 million last year, 157 times a standard man- ual worker's wage.

Mr Martin Taylor, deputy chairman of Hanson (whose eponymous chairman's salary last year was £1.35 million), com- ments simply that directors' remuneration 'is about the rate for the job and reward for, performance; it's a matter for the share- holders to deal with if they're unhappy'.

But many other observers wedded to the principles of red-blooded capitalism are nevertheless critical of the way in which, in practice, the salary trend has begun to feed on itself — by a combination of spurious comparability, ineffectual corporate gover- nance and sheer greed — and is presented to shareholders as a fait accompli. Blenyth Movements in Chief Executive and Manual Earnings 1980-1992

— Chief executives Manual employees

Source: IDS Management Pay Review Jenkins of the Institute of Directors, Lord Archer's interviewee on the Jimmy Young show, warns of 'excessive or unjustified awards which bear the seeds of their own destruction, diminisli. the credibility and standing of companies and create hostility among employees, shareholders and the general public'.

One eloquent critic in the same vein is Sir Owen Green, who retires this month after nine dramatically successful years as chairman of the conglomerate BTR, having accepted a pay rise for his last year of only £804, to a modest £217,616. During Sir Owen's time, BTR's profits have grown from £400,000 to over £1 billion. He believes that 'in every walk of life, leader- ship is partly a matter of example'. When times are hard, he says, corporate chiefs, although they can still be fairly rewarded for good performance, have a duty to demonstrate reasonableness, proportion and frugality. It is a message which the director-general of the BBC, for example, has belatedly understood, if at all.

Sir Owen particularly disapproves of huge differentials at the top of large, well- established companies whose bosses have simply risen through a lifetime career pyra- mid. 'There's absolutely nothing to be said against entrepreneurs or pop stars creating personal wealth through their own talent, direct from the general public. But in many large companies the people at the top are 'And if we don't stop fighting, they're going to bomb the place!' really a type of functionary — the culture and the strategy are already set. In any business which has not been created or dis- tinctly improved by a single person, I can't see any justification for or any good exam- ple being set by trying to keep up with [entrepreneurs], who are entirely different animals.'

The distinction between entrepreneurs and functionaries is important to the debate. Lord Hanson is an employee of his company but he is also its founding genius. Shareholders in Hanson plc who have seen earnings per share multiply eight times in the past 12 years, and many more times over the past 30, are unlikely to begrudge their chairman his £1.35 million salary. Lord King at British Airways (£669,350) would certainly count as an individual who has 'distinctly improved' his company; as would Sir Owen himself at BTR.

But at the other end of the scale, why should a water board chairman suddenly jump from £70,000 to £140,000 because the Government has sold his company's shares on the stockmarket? Other than the bur- den of occasional communication with shareholders rather than civil servants, his job has hardly changed at all. To whom is he suddenly comparable, apart from half a dozen other time-serving water engineers who happened to be in situ when the indus- try was privatised? Is anyone prepared to offer such people a £140,000 job in a differ- ent industrial sector?

The last question is also crucial. The very wide variation in top salaries even within similar industries tells us that there is cer- tainly no perfect market for chief execu- tives and chairmen. The number who move from one company to another is relatively small, and those who do so are more likely to be motivated by prestige, or the need for something else to do when retirement looms, than by pure cash. Many loyal and ambitious men in secure corporate hierarchies like Unilever and BT would never leave for another company however much they were offered, and there is therefore no 'market' reason to pay them more.

Comparability is often a convenient myth: it means keeping up with a meretri- cious external benchmark, even when there is little likelihood of the executive in ques- tion seeking or being offered another job. And 'up' is the operative word: it is hard to imagine the chief executive of the Chel- tenham & Gloucester building society (£281,000) agreeing that the appropriate bench-mark for next year would be his opposite number at the neighbouring Bris- tol & West (£195,000). But it is easy to imagine the reverse.

The importance of international compar- isons, according to Sir Owen Green, is 'greatly exaggerated'. How many British businessmen have ever been appointed to run major American corporations? In the financial sector, Sir Denis Weatherstone of J.P. Morgan in New York is a notable loss to British banking. But in industry the flow is, if anything, in this direction across the Atlantic — including such worthies as Sir Ian MacGregor and Sir Graham Day.

My former colleagues in the City are often attacked for leading the salary boom: Britain's highest paid executive of the late 1980s was Christopher Heath, a stockbro- ker with Barings (£2.5 million plus). But in the financial sector there is genuine inter- national comparability — an equity sales- man can move from London to New York or Tokyo tomorrow and do exactly the same job. There is little corporate loyalty, lor job security. The City job market is mobile and the salary scale is transparent, even if it has become grossly inflated.

The City has also realised that senior executives do not have to be paid more than their underlings — a warrant trader from Essex can be paid twice as much as the chairman, if his particular activity has chipped in an extraordinary profit for the year. Privatised utilities, by contrast, have used the high cost of recruiting finance directors from outside to justify bumping up the salaries of home-grown chief execu- tives, so that amour-propre in the board- room is pandered to.

Comparability may be a useful concept if rigorously applied, but at senior levels it has become a sloppy, cynical excuse for an endless game of salary leap-frog. The men- tality was perfectly illustrated by a Bank of England spokesman who tried to justify a controversial raise for the Governor (a pure functionary by any definition) by pointing out that Mr Leigh-Pemberton 'was in danger of being overtaken by Jeremy Paxman'.

Excess is not just a feature of what the modern boss takes home by way of current salary whilst he occupies his chair. It is often to be found in his departure arrang- ments as well. Greatly accelerated pension contributions can be a hidden cost of recruiting a middle-aged chief from out- side. A giant salary leap slipped in at the end can boost the level of the outgoing chairman's pension, making a correspond- ingly hefty dent in the pension fund — Sir Anthony Tennant of Guinness, whose base salary went up by 24 per cent to £777,000 for his farewell year, looks like an outright winner in this category, and he even col- lected a special pension top-up of £204,000 a year above his normal company entitle- ment. And for those who depart early when things go wrong, a service contract with several years to run ensures a comfortable cushion to fall back on: Sir Kit McMahon collected an extra £489,187 when he passed Go at Midland Bank.

Much attention has been given in the recent Cadbury guidelines on corporate governance to the function of remunera- tion committees in deciding senior salary packages. Such bodies are made up of non- executive directors and are open to outside advice on the mysteries of comparability. But strong-willed chairmen have little diffi- culty in steering board committees wherev- er they want them to go. And, to the extent that non-executives of one company are very frequently senior executives of other companies, they all have a vested interest in perpetuating a system in which the aim is to get paid as much as you possibly can without incurring the wrath of the share- holders.

But even if severely provoked, share- holders of large companies are too diffuse to convert their anger into specific repri- mands to chairmen. Institutional sharehold- ers rarely make a fuss about salary decisions. According to Sir Owen, 'Institutions behave as investors rather than owners; they don't seem to be concerned about the top man's package so long as their investment appreci- ates at a satisfactory rate.'

One reason why the top people's pay bonanza runs on unchecked is that, because of the small number of individuals involved, huge raises have little effect on profits and therefore on returns to share- holders — unlike modest wage increases for the mass of shop-floor employees. But in the United States, share-option schemes have become so lavish that as much as 8 per cent of some companies has been offered as incentives to a handful of senior employees, representing a significant dilu- tion of earnings for ordinary investors. Last year's highest-paid executive, for example, the exceedingly fortunate Thomas Frist of the Hospital Corporation of America, realised $127 million.

The situation in Britain is far from such extremes, but a bandwagon is beginning to roll against disproportionate rewards in a time of austerity on both sides of the Atlantic. Intrusive legislation (which the Clinton camp has threatened) would be a retrograde step, but public irritation can at least lead to stronger codes of practice.

Here, for a start, are some guidelines for remuneration committees to chew on: reward performance by strictly objective criteria, preferably earnings-per-share growth; make sure that total pay, like the share values to which it relates, can go down as well as up; don't create unneces- sarily wide differentials between the top men and the next layer of senior manage- ment; don't offer contracts which guaran- tee enormous pay-offs to those who fail in their jobs; don't stick the spoon in the pen- sion fund; estimate the value of share options, and explain what they mean to the rest of the shareholders. Above all, remem- ber that to run a company is not a prize, but a responsibility.

Meanwhile, the boom in top people's pay greed is gathering momentum. 'Sharehold- ers won't be able to stop it,' Sir Owen Green concludes. 'Moderation will have to come through pressure of public opinion.' Mr Major is right: the British do have an instinct for fairness, and it is offended by the sight of our business leaders with gravy running down their chins.

Previous page

Previous page