ARTS

Dance

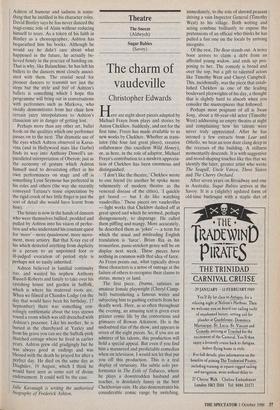

Ashton's legacy

Julie Kavanagh

of on the heels of the obituaries come the tributes to Ashton on television and radio: Omnibus (BBC 1, 30 Septem- ber) Kaleidoscope (Radio 4, 7 October) and Meridian (BBC World Service, 9.30 p.m., 11 October). And on 29 November a memorial service will be held for him at Westminster Abbey, the appropriate place for England's greatest poet of the dance.

I have spent the last few weeks as consultant on the Omnibus celebration, interviewing over 20 of Ashton's friends and colleagues. The producer, Julia

Matheson, wanted the programme to be an enjoyable medley of impressions, stories and dance rather than a serious appraisal of Ashton's place in dance history: 'It's too soon for that, everyone is still too stunned by his death.' They were indeed - a few were moved to tears remembering him but I was surprised by how ungushing and eloquent people turned out to be, particu- larly the dancers, who are rarely good at verbalising any aspect of their art.

Ashton had several very different circles of friends whom he tended to keep apart. To represent what he called his 'grand life' we filmed the Marchioness of Salisbury, as they were good friends with a shared love of old-fashioned flowers and Ashton was a regular guest at Hatfield. Lady Salisbury found him rather shy with a child-like enjoyment of stately living. When they danced together at a ball at Buckingham Palace, he came out with a favourite line: 'Here am I, little Freddie Ashton from Peru, and look at me now!'

Unlike, say, Cccil Beaton, Ashton was not a snob. He never courted society, in fact he seldom returned an invitation and would never go anywhere without being fetched and carried. He relied on being able to ring up old 'chums' like William Chappell and Alexander Grant and invite himself to dinner; and when they went to stay with him they: always brought their own food. (It Was Grant who treated Ashton to what turned out to be a valedic- tory lunch of lobster and champagne the day before he died.)

Ashton's unthrusting nature - which he caricatured so brilliantly as the Ugly Sister in Cinderella - was one quality which endeared him to celebrated hostesses who couldn't resist mothering him. And of course he fitted in. Anywhere and with anyone. He would also sing for his supper- he was 'proper fun', as Diana Cooper once told me. His imitations were legendary and he was a riveting raconteur (though he hated the term, associating it with bores). His friends have tended to be wary of retelling his anecdotes, knowing that their wit lay as much in Ashton's droll delivery and impeccable timing as in the content. They have also been reluctant to name victims of his mimicry except for Pavlova, his all-time inspiration and most spon- taneous party piece.

Ashton was a terrific giggler most of his life: even as adults he and his sister Edith would sit behind someone with an elabo- rate hairdo on a bus and pull out all the pins. In his last years, though, he com- plained that nothing made him laugh any more and the most you could get out of him was a sort of hedgehoggy snuffle. He adored society but being alone was impor- tant to him too and he would say it was then that he questioned his talent. For him solitude was always edged with loneliness: his housekeeper Mrs Dade told us how he used to talk her into watching him play game after game of patience to dissuade her from going home.

This Shakespearian overlapping in Ashton of humour and sadness is some- thing that he instilled in his character roles. David Bintley says he has never danced the tragi-comic role of Alain without reducing himself to tears. As a token of his faith in Bintley as a choreographer, Ashton has bequeathed him his books. Although he would say he didn't care about what happened in the future, he actually be- lieved firmly in the practice of handing on. That is why, like Balanchine, he has left his ballets to the dancers most closely associ- ated with them. The crucial need ' for Pioneer dancers to transmit not just the steps but the style and feel of Ashton's ballets is something which I hope this programme will bring out in conversations with performers such as Markova, who vividly demonstrates from her chair how certain jazzy interpolations to Ashton's classicism are in danger of getting lost.

Perhaps more than any other art, ballet feeds on the qualities which one performer passes on to the next. The dramatic use of the eyes which Ashton observed in Karsa- vina (and in Hollywood stars like Garbo) finds its way into Anthony Dowell's un- paralleled interpretation of Oberon; just as the economy of gesture which Ashton himself used to devastating effect in his own performances on stage and off is something Lynn Seymour has perfected in his roles and others (the way she recently conveyed Tatiana's tense expectation by the rigid crook of her little finger is just the sort of detail she would have learnt from him).

The future is now in the hands of dancers who were themselves bullied, prodded and pulled by Ashton into his vision of perfec- tion and who understand his constant quest for 'more' – more epaulement, more move- ment, more artistry. But that X-ray eye of his which detected anything from duplicity in a person to an unpointed foot or ill-judged evocation of period style is perhaps not so easily inherited.

Ashton believed in familial continuity too, and wanted his nephew Anthony Russell-Roberts and family to take over his ravishing house and garden in Suffolk, which is where his maternal roots are. When we filmed at Chandos Lodge (on the day that would have been his birthday, 17 September) there was something con- solingly emblematic about the toys strewn round a room which was still drenched with Ashton's presence. Like his mother, he is buried in the churchyard at Yaxley and from his grave you can see the Suffolk-pink thatched cottage where he lived in earlier years. Ashton grew old grudgingly but he was always good at endings and was blessed with the death he prayed for after a Perfect day. He died on the same day as Diaghilev, 19 August, which I think he would have seen as some sort of divine endorsement. It could well be the case.

Julie Kavanagh is writing the authorised biography of Frederick Ashton.

Previous page

Previous page