BOOKS

Finding God on imperial grounds

William Dalrymple

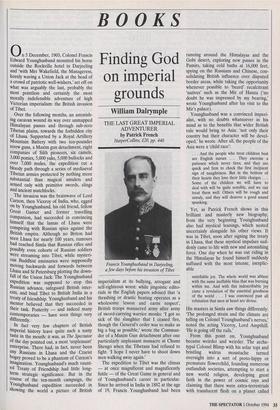

THE LAST GREAT IMPERIAL ADVENTURER by Patrick French HarperCollins, £20, pp. 440 On 5 December, 1903, Colonel Francis Edward Younghusband mounted his horse outside the Rockville hotel in Darjeeling and 'with Mrs Wakefield, the Manageress, keenly waving a Union Jack at the head of a crowd of patriotic well-wishers,' set off on what was arguably the last, probably the most pointless and certainly the most morally indefensible adventure of high Victorian imperialism: the British invasion of Tibet.

Over the following months, an astonish- ing caravan wound its way over unmapped Himalayan passes and through sub-zero Tibetan plains, towards the forbidden city of Lhasa. Supported by a Royal Artillery Mountain Battery with two ten-pounder screw guns, a Maxim gun detachment, eight companies of Sikh pioneers, six camels, 3,000 ponies, 5,000 yaks, 5,000 bullocks and over 7,000 mules, the expedition cut a bloody path through a series of mediaeval Tibetan armies protected by nothing more substantial than magical amulets and armed only with primitive swords, slings and ancient matchlocks.

The invasion was the brainwave of Lord Curzon, then Viceroy of India, who, egged On by Younghusband, his old friend, fellow Great Gamer and former travelling companion, had succeeded in convincing himself that the lamas of Lhasa were conspiring with Russian spies against the British empire. Although no Briton had seen Lhasa for nearly 100 years, rumours had reached Simla that Russian rifles and Possibly even cohorts of Russian soldiers were streaming into Tibet, while mysteri- ous Buddhist emissaries were supposedly moving backwards and forwards between Lhasa and St Petersburg plotting the down- fall of the Union Jack. The Younghusband expedition was supposed to stop this Russian advance, safeguard British inter- ests, and bind Tibet to British India in a treaty of friendship. Younghusband and his mentor believed that they succeeded in their task. Posterity — and indeed many contemporaries — have seen things very differently. . In fact very few chapters of British imperial history leave quite such a nasty taste in the mouth: it was, as The Spectator of the day pointed out, a most 'unpleasant' enterprise. There had, in fact, never been any Russians in Lhasa and the Czarist bogey proved to be a phantom of Curzon's imagination. Younghusband's much vaunt- ed Treaty of Friendship had little long- term strategic significance. But in the course of the ten-month campaign, the Younghusband expedition succeeded in showing the world a picture of British Francis Younghusband in Darjeeling a few days before his invasion of Tibet imperialism at its bullying, arrogant and self-righteous worst: while jingoistic edito- rials in the English papers advised that 'a thrashing or drastic beating operates as a wholesome lesson and earns respect', British troops massacred army after army of sword-carrying warrior monks: 'I got so sick of the slaughter that I ceased fire, though the General's order was to make as big a bag as possible,' wrote the Comman- der of a Maxim Gun detachment after one particularly unpleasant massacre at Chumi Shengo when the Tibetans had refused to fight. 'I hope I never have to shoot down men walking away again.'

The expedition to Tibet was the climax — at once magnificent and magnificently futile — of the Great Game in general and of Younghusband's career in particular. Since he arrived in India in 1882 at the age of 19, Francis Younghusband had been running around the Himalayas and the Gobi desert, exploring new passes in the Pamirs, taking cold baths at 16,000 feet, spying on the Russians and Chinese, con- solidating British influence over disputed border areas, while taking the opportunity whenever possible to 'beard' recalcitrant `natives' such as the Mir of Hunza (`no doubt he was impressed by my bearing,' wrote Younghusband after his visit to the Mir's palace).

Younghusband was a convinced imperi- alist, with no doubts whatsoever in his mind as to the benefits that wider British rule would bring to Asia: 'not only their country but their character will be devel- oped,' he wrote. After all, the people of the Asia were a 'child race': . . And the people who treat children best are English nurses . , . They exercise a patience which never tires; and they are quick and firm to check the first incipient sign of naughtiness. But in the bottom of their hearts they love their little charges . . . Some of the children we will have to deal with will be quite sensible, and we can treat them well. Others will be rough and unruly, and they will deserve a good sound spanking.

Yet, as Patrick French shows in this brilliant and masterly new biography, from the very beginning Younghusband also had mystical leanings, which nested uncertainly alongside his other views. It was in Tibet, soon after signing the treaty in Lhasa, that these mystical impulses sud- denly came to life with new and astonishing force. One day when he was out riding in the Himalayas he found himself suddenly suffused with the most intense, inexplic- able

untenable joy. The whole world was ablaze with the same ineffable bliss that was burning within me. And with this indescribable joy came a revelation of the essential goodness of the world . . . I was convinced past all refutation that men at heart are divine.

His masters in Simla saw things differently: `The prolonged strain and the climate are telling on Colonel Younghusband's nerves,' noted the acting Viceroy, Lord Ampthill. `He is going off the rails.'

From this point on, Younghusband became weirder and weirder. The arche- typal Colonel Blimp with his solar topi and bristling walrus moustache turned overnight into a sort of proto-hippy or premature flowerchild, founding numerous outlandish societies, attempting to start a new world religion, developing great faith in the power of cosmic rays and claiming that there were extra-terrestrials with translucent flesh on a planet called Altair. Finally, at the end, as the bombs fell during the Blitz, Younghusband — now steeped in Buddhist and Hindu philosophy — was busy with his new lover attempting to father the Messiah who would Save the Human Race. The Orient had had its revenge.

It is an odd life, yet a strangely symbolic one, epitomising the complexity of the impact that Asia — and India in particular — had on the British. Younghusband was unique, yet he was also very much of his time, highlighting many of the contradic- tions inherent in the Edwardian English, uncomfortably sandwiched as they were between the straight-laced Victorian past and the new ideas of the 20th century. In Patrick French, Younghusband has found a biographer with the necessary imagination and sufficient range of qualities and sympa- thies to bring out the significance of his life, and to make comprehensible a set of attitudes, certainties and prejudices as baffling to us as the Tibetans' were to the Edwardian British.

After all, what can you make of a man who could spend the day ordering entirely unnecessary assaults on Tibetan positions, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of virtu- ally unarmed people, and who could then retire to bed to read Annie Besant ('I am reading another most beautiful book,' he wrote to his wife, Helen, from Tibet. 'Its about Cosmic Consciousness which I will explain to you some time and which gives a most intensely beautiful and peaceful idea of the universe'); who was so stiff with women in his younger military days that his idea of flattery was to write to a pretty female correspondent telling her that she `would make a Splendid Colonel of a Cav- alry Regiment' if she were a man; yet who, towards the end of his life, began advocat- ing free love and who took his last lover at the grand old age of 76?

This is a wonderful book: beautifully written, wise, balanced, fair, funny and above all extremely original. It is the prod- uct of an obsession — the author found that the Colonel colonised no less than five years of his life — and French ingeniously weaves the story of his own detective work in London libraries, Indian archives, remote Tibetan passes and Dorset attics into the narrative, producing a new hybrid in the process: a travelling biography, one part Michael Holroyd, one part Robert Byron with a dash of John Buchan (and even a little Monty Python) thrown in for good measure. In his strange and riveting tale of Younghusband's metamorphosis, Patrick French has made an altogether brilliant debut, and it seems extremely unlikely that a more amusing or more inno- vative biography will be written this decade.

William Dallymple's Delhi: City of Djinns recently won the Thomas Cook Travel Book Award and the Sunday Times Young British Writer of the Year Prize.

Previous page

Previous page