`MY IDEA OF FUN ISN'T DISCUSSING POLITICS'

On the eve of the annual Labour Party conference, Noreen Taylor

tracks Tony Blair to his lair in the House of Commons and attempts to find out if the Labour leader is as nice as he looks

BEFORE INTERVIEWING Tony Blair I phoned a few of his friends. I wanted to hear the behind-the-scenes gossip about Mr Nice Guy. In all the other outrageously complimentary profiles, there was only the well-worn mantra: he is delectable, electable, a prime, market-tested purveyor of consumer-friendly socialism. There had to be something else. And the few who do know him want you to believe there is. That golden boy role might be all right for a week's performance in rep but it isn't sufficiently compelling for a two-year run on the national stage up to the next election.

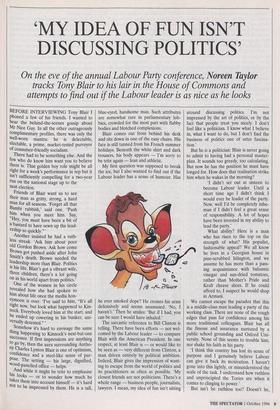

Friends of Blair want us to see their man as gritty, strong, a hard man for all seasons. 'Forget all that Bambi rubbish,' said one. 'Push him when you meet him. Say, "Hey, you must have been a bit of a bastard to have sewn up the lead- ership so quickly." Another insisted he had a ruth- less streak. `Ask him about poor old Gordon Brown. Ask how come Brown got pushed aside after John Smith's death. Brown needed the leadership more than Blair. Politics is his life. Blair's got a vibrant wife, three children, there's a lot going on in his world apart from politics.' One of the women in his circle revealed how she had spoken to him about life once the media hon- eymoon is over. 'I've said to him, "It's all right now, but look what happened to Kin- flock. Everybody loved him at the start, and he ended up cowering in his bunker, uni- versally detested." Somehow it's hard to envisage the same thing happening to Kinnock's next-but-one successor. If first impressions are anything to go by, then the aura surrounding Antho- ny Charles Lynton Blair is one of optimism, Confidence and a steel-like sense of pur- pose. The setting — his large, dignified, wood-panelled office — helps. And while it might be trite to emphasise his looks — or to wonder how much he takes them into account himself — it's hard not to be impressed by them. He is a tall, blue-eyed, handsome man. Such attributes are somewhat rare in parliamentary lob- bies, crowded for the most part with flabby bodies and blotched complexions.

Blair comes out from behind his desk and sits down in one of the easy chairs. His face is still tanned from his French summer holidays. Beneath the white shirt and dark trousers, his body appears — I'm sorry to be trite again — lean and athletic.

My first question was supposed to break the ice, but I also wanted to find out if the Labour leader has a sense of humour. Has he ever smoked dope? He crosses his arms defensively and seems unamused. 'No, I haven't.' Then he smiles: 'But if I had, you can be sure I would have inhaled.'

The sarcastic reference to Bill Clinton is telling. There have been efforts — not wel- comed by the Labour leader — to compare Blair with the American President. In one respect, at least Blair is — or would like to be seen as — very different from Clinton, a man driven entirely by political ambition. Indeed, Blair gives the impression of want- ing to escape from the world of politics and its practitioners as often as possible. 'My closest friends are not politicians. There's a whole range — business people, journalists, lawyers. I mean, my idea of fun isn't sitting around discussing politics. I'm not impressed by the art of politics, or by the fact that people treat you nicely. I don't feel like a politician. I know what I believe in, what I want to do, but I don't find the business of politics one of utter fascina- tion.'

But he is a politician: Blair is never going to admit to having had a personal master- plan. It sounds too greedy, too calculating. But now he has the position he must have longed for. How does that realisation strike him when he wakes in the morning?

`I didn't set out at sixteen to become Labour leader. Until a short time ago I didn't think I would ever be leader of the party. Now, well I'd be completely inhu- man if I didn't feel a great sense of responsibility. A lot of hopes have been invested in my ability to lead the party.'

What ability? Here is a man who has risen to the top on the strength of what? His populist, fashionable appeal? We all know he lives in a Georgian house in pine-scrubbed Islington, and we assume he has more than a pass- ing acquaintance with balsamic vinegar and sun-dried tomatoes, rather than Mother's Pride and Kraft cheese slices. If he could afford to, I suspect he would shop in Armani.

We cannot escape the paradox that this is a middle-class man leading a party of the working class. There are none of the rough edges that pass for confidence among his more traditional colleagues. Blair has all the finesse and assurance nurtured by a public school grounding and Oxford Uni- versity. None of this seems to trouble him, nor shake his faith in his party.

`I think this country has lost its sense of purpose and I genuinely believe Labour can give it back its motivation. I haven't gone into this lightly, or misunderstood the scale of the task. I understand how ruthless and unprincipled the Tories are when it comes to clinging to power.'

But isn't he ruthless too? Doesn't he, equally, want power? The cool, blue gaze remains. 'I am determined, but I don't view myself as ruthless. I joined the Labour Party, not through my background, not because I wanted to be a career politician, but because I knew at its heart the Labour Party had a set of beliefs that would allow the individual to flourish.

`Believe me, fighting the '82 Beaconsfield by-election for Labour was hardly seen as a smart career move. Michael Foot was struggling with the problems of leadership, Tony Berm was in charge of policy, Arthur Scargill was leading the trade unions, and we were in the middle of the Falklands war.

`There was a point when it seemed as though Labour could have gone out of business as a serious party. But I never believed that. I always thought there was enough goodness there to rescue it. If I hadn't viewed politics as a vocation rather than a career, it would have been a strange choice then to have decided that my future was with the Labour Party.'

Vocation is a word that regularly crops up when he is discussing his political beliefs, and one is reminded that like his wife, the barrister Cherie Booth, Blair is a committed Christian.

`I think the basic principles of Christiani- ty and democratic socialism are very sym- pathetic to each other. Essentially, both care about people and consider that the conditions in which we live are governed by the world around us.'

Blair's view that a compassionate society does not necessarily exclude efficiency and material success is one of the main planks on which he plans to build his modernised, new-look party. But how is he going to con- vince voters that socialism for the Nineties isn't another way of emptying their wallets?

'We have made it clear that we will put forward our tax plans at an appropriate time. The critical principles that determine our approach are well known. Under the Conservatives we now spend more tax pro- portionately than we did under the last Labour government. We are taxing people highly in order to pay the bills of social decay. Now if you want to get tax down you have to tackle the underlying problems.

`What I've been trying to do since I got elected is to show how the Conservatives are fundamentally wrong. Their view of society is one where the individual is a vic- tim of crude laissez-faire market forces, where only the few matter.

`This is a false view of how a society can prosper because if you have a large minori- ty cut off, alienated, set adrift, you cannot run a modern economy. You cannot allow these current levels of unemployment, where children are brought up in unstable conditions with crime and drugs as part of their daily lives. Now that is my conviction and I have got to present that in the best way possible.'

This approach seems to address the fears of someone like the comic Ben Elton, who said recently, 'I'll vote Labour because I'm selfish. I'm fed up coming out of a West End theatre and falling over beggars. I'm fed up having my car broken into by disen- franchised, no-hope kids.'

Former Tory voters, wondering whether they should cross over to Blair's well modu- lated middle-class brand of socialism, might also find his passion seductive.

Yet some of his answers betray one Blair trait: the smart, intelligent view can deteri- orate into the kind of glib rhetoric that has been Labour's hallmark down the years. It's as if he has swiped the megaphone from an old windbag, made an excellent couple of points, and then floundered into windbag territory himself. On such occa- sions he does himself a disservice, but he is aware that his brand of conviction politics will inevitably be compared to that of Lady Thatcher.

He says, 'A lot of nonsense was talked about Thatcher being a great conviction politician, but, goodness, she took care that her message was properly presented. Saatchi weren't brought in to bolster her convictions but to bolster her presentation.'

Mr Blair is a great believer in the power of presentation. His detractors point out that there is little substance, merely a pleasing, decorative icing. 'There are cer- tain attributes essential to the professional conduct of business,' he says yith a hint of exasperation. 'It's like appearing at a press conference in a suit rather than pyjamas. Just like a journalist' — oh dear, this is get- ting personal — 'having to turn up on time with a command of decent English.'

But the British journalist, even the most inarticulate, can never be accused of fence- sitting, which is one of the main accusa- tions levelled against Mr Blair's carefully chosen words.

`Yes, I know what's being said. But we have been clear in stating what the dividing lines are between the parties. Take crime. Until now, all the Tories have had to do is walk around saying, "Labour are in favour of criminals and we're not." They didn't think they would have to do anything about rising crime figures until we spoke up in opposition to them. Until then, they'd done damn all about it. Now that's fence-sitting.'

He widens the argument a little. 'Our real disagreement with the Tories is not that they believe in a market economy and we don't. Of course we believe in a market economy, but I don't think the character of any party becomes clear until you're in I hope I don't evolve into that LibDem bird.' power. You are always reacting to someone else's agenda.'

True, but the thought that a political party reveals its true colours only when in power is precisely the fear that holds back many disaffected Conservative voters from embracing the alternative.

For a man who had assured me that he didn't find the business of politics one of utter fascination, it was remarkably difficult to prise the Labour leader away from the topic, especially when I attempted to move on to the matter of his personal life. Most of my attempts were swiftly and subtly rerouted into the cul-de-sac of polemic.

Yet the candid smile and the cosy man- ner create an ambiance in which I would expect secrets to be confided. He kept stressing instead how in touch he was with `normal, everyday life'.

`I have no desire to be locked into that hermetically sealed world of the House of Commons. My wife works, so I have to help in the house, looking after our three children. I've done the middle-of-the-night nappy changes, but I don't see anything abnormal or new-mannish about that. Why should all the family obligations fall on my wife? Anyway, I quite enjoy it.

`Take the other weekend. Cherie had to work and I took the children to the park. I don't see that as a matter for congratula- tions. It's just normal, the way parents of school kids behave.' Blair's children have not followed in his footsteps: they attend state schools.

So far as Tony Blair is prepared to dis- cuss such matters, his taste in music and books veers towards the traditional. 'I lis- ten to Classic FM a lot. I don't know a great deal about new writers. Cherie is the one who keeps up with the latest books. I tend to read historical biographies, and Wodehouse and Dickens, probably because I use reading as a form of escapism. Per- haps there's enough reality in politics.' It's hard to imagine John Prescott, just for example, reading with anything other than righteous outrage the works of P.G. Wodehouse. But as the privately educated son of a Tory, one of the 'haves', Tony Blair grew up untouched by the social decay that breeds anger, resentment, as well as union leaders and traditional Labour politicians. He must derive a cer- tain satisfaction from having broken the mould.

`I don't look at things that way. I know there are certain situations that make me angry, and I know that you have to be in power to put forward policies that will change those situations. I care that children are wandering the streets at night alone because their parents are working and they can't afford child-care.

`I care about old people who live on housing estates not being able to sit outside on a summer evening peacefully because they're frightened of being pestered. To me, there is something intellectually and morally distasteful about a society that allows those sort of ills to remain uncor- rected.'

But he is also aware that for the past 15 years his party has been impotent, and in the years before was locked into a self-destruc- tive cycle which saw capitalism as the enemy and trade unions as heroes. He clearly hasn't fought for the leadership to become trapped into fighting those old battles.

`I knew that the party had to change not its principles, but that it had to mod- ernise the application of those principles. Now I know what needs to be done to get Labour into power, and what I've tried to do since becoming leader is to break out of some of the political strait-jackets we've been in for the last 30 years. Not because I'm interested in the trappings of power, but because I believe in the validity of what I'm doing. We've lost four elections. We need to get it right this time. And we will.'

I really think he believes it. Bambi has teeth.

Noreen Taylor is on the staff of the Daily Mirror.

Previous page

Previous page