Dan Flavin (Serpentine Gallery, till 23 September)

Pillars of light

Andrew Lambirth

Minimalism, the less-is-more' philosophy applied to painting and sculpture in the mid-1960s, is both popular and influential once again in the purlieus of the British art establishment. Employing simple and impersonal forms, minimalism was conceived as an antidote to the self-dramatisation of pop art and abstract expressionism, and geared to the low-key exploration of colour, light and space. Dan Flavin

(1933-96), who is principally known for his installations of fluorescent tubing, is looked upon as one of the founders of minimal art, along with Carl Andre, Sol Lewitt and Donald Judd. But Flavin himself reacted against the label, insisting on the boldness and diversity of his designs, which, if anything, tended he thought towards 'maximalism'. The current show of 22 of his works at the Serpentine offers us the chance to decide for ourselves.

As befits the minimalist ethic, there is nothing remarkable about the materials which Flavin employed, These are readymade fluorescent light fixtures, commercially available in ten colours only: blue, green, pink, red, yellow, ultraviolet and four whites (cool white, warm white, soft white and daylight white). The bulbs are sold in two, four, six or eight-foot lengths. Flavin arranged them in parallel or at angles to each other, mixing his prepared palette of coloured light effects carefully. He used the fluorescent tubes to articulate and enliven space, and enjoyed the relationship his work developed between the architecture of a gallery and its sources of natural light. I had expected the Serpentine's galleries to be blacked out, but this is not the case. The windows in the external walls and the park setting are in fact wellsuited to the installation.

The first piece you see as you enter the galleries is also Flavin's first fluorescent sculpture. Entitled 'the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi)', it consists of a manifestly phallic rod of gold light, which Flavin also called 'the diagonal of personal ecstasy', and compared to Brancusi's 'Endless Column' in its 'uniform elementary visual nature'. Before constructing this piece, Flavin — who had no artistic training — had made watercolours, and had been experimenting with light only for a couple of years. His early education in a Roman Catholic seminary had perhaps predisposed him towards icons, for it was a sort of icon that he had been making immediately prior to this fluorescent wall sculpture. The icon idea provides a link with Russian constructivist art — a seminal influence on minimalism — and the abstract 'icons' produced by such luminaries as Malevich and Tatlin, often featuring the dynamic compositional diagonal appropriated here by Flavin.

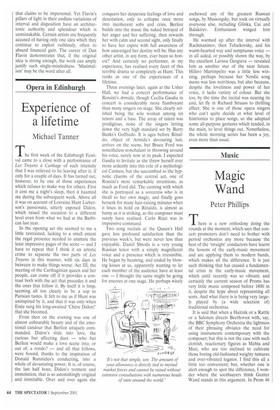

Adjacent is a daylight white vertical piece in three parts called 'the nominal three (to William of Ockharn)', while a third sculpture, 'untitled (to Henri Matisse)', makes up this room's quota. The Matisse homage is composed of pink, yellow, blue and green striplights — Flavin's primary colours which go to make up 'white' light. (At the opposite end of the spectrum, a sculpture dedicated to Ad Reinhardt is composed of blue fluorescent light and filtered ultraviolet — aptly known as 'black light'.) Passing into the side gallery which has views over the park, the visitor encounters a long green-lit barrier (illustrated above), like a stepped gate, which engages in rhythmical dialogue with the window pattern. This large piece has the weird optical effect of turning the grass outside the windows pink. (This light barrier should perhaps be dedicated to Mondrian, who once complained that the countryside was too green; not in Flavin's world.) Move directly into the central hall and the walls here also look pink, until your eyes have adjusted and the wails resume their customary whiteness. Here are six 'monuments to Tatlin' in cool white, inspired by Tatlin's Tower — his 'Monument to the Third International' (1919). This room is the core of the exhibition, seeming in its purity to propose a bright white future as symbolised by images of abstract energy and skyscrapers, emblems of industry and technology. The radiance of these pieces, and their immateriality, is not far removed from an aura of spirituality, though Flavin himself resented any spiritual interpretation of his work — 'It is what it is, and it ain't nothing else,' he asseverated gruffly.

Alas, what the artist wants or directs may not be how the audience reacts. If some see intimations of the sacred here, others find that Flavin's dedication of his sculptures to friends or fellow artists personalises an art that claims to be impersonal. Yet Flavin's pillars of light in their endless variations of interval and disposition have an architectonic authority and splendour which is unmistakable. Certain artists are frequently accused of having only one idea which they continue to exploit ruthlessly, often to absurd financial gain. The career of Dan Flavin demonstrates that, if the original idea is strong enough, the work can amply justify such single-mindedness. 'Maximalism' may be the word after all.

Previous page

Previous page