THE KURDS' NEW BEST FRIEND

Charles Glass finds

that Iran is the Kurds' greatest benefactor

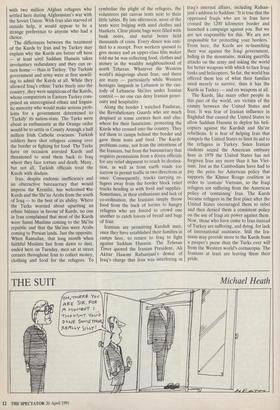

Teheran MOST of the Kurds fleeing from Iraq are not at liberty to decide whether to remain at home or to escape. Nor can they choose the direction of their exodus. All they can do is run, along any road the Iraqis are not strafing, towards the nearest border, from the moment they see or hear the approach of an Iraqi army. Most have gone to Iran, many to Turkey and only a few to Syria not much of a selection, but the only neighbours the Iraqi Kurds have. Iraqi garrisons in Mosul and the Sinjar Hills, the only army posts not dislodged during last month's Kurdish revolt, block the way to Syria in the West. That leaves Turkey in

the North and Iran in the East. If I were a Kurd and had a choice, I would probably opt for Iran.

Turkey is a tempting prospect. The community of nations has bestowed most of its beneficiaries on Johnnie Turk, loyal Nato ally and, by virtue of his application for Community membership, honorary European. The United States is bombard- ing Turkey with blankets and tents and has promised that its soldiers based in Turkey will feed as many as 700,000 people daily. The State Department estimates the Un- ited States government has spent £53 mil- lion, all of it in Turkey, to assist the Iraqi refugees. Britain says there have been 18 relief flights sent to help the Kurds, of which 16 have gone to Turkey. The Islamic Republic does not offer the same financial attractions to the prospective refugees. Although the European Community has pledged two thirds of its $180 million Iraqi refugee budget to Iran, the money has not arrived here.

Meanwhile, the refugee exodus has not abated. The United Nations' High Com- missioner for refugees, a small Japanese woman named Sadako Ogata, was apparently horrified when she visited an Iran-Iraq border. 'Numerically, we know this is the largest exodus of people in the shortest period of time,' she told reporters who accompanied her to the border. (As a good Japanese, she took a television crew from NHK, one of the Japanese networks, with her — just as a visiting British Minister had a television team from the BBC with him, lest the public be unaware of his heroism.) More than a million human beings have fled here from north- ern Iraq as well as thousands of Shi'ite Arabs from the South, all on foot or in battle-scarred cars and trucks. Iran is overcrowded, not only with the destitute victims of Saddam Hussein's army, but with two million Afghan refugees who settled here during Afghanistan's war with the Soviet Union. With Iran also starved of outside help, it would appear to be a strange preference to anyone who had a choice.

The differences between the treatment of the Kurds by Iran and by Turkey may explain why the Kurds are better off here — at least until Saddam Hussein takes involuntary redundancy and they can re- turn home — than in Turkey. The Turkish government and army were at first unwill- ing to admit the Kurds at all. While they allowed Iraq's ethnic Turks freely into the country, they were suspicious of the Kurds, whose compatriots in Eastern Turkey com- prised an unrecognised ethnic and linguis- tic minority who would make serious prob- lems for a government determined to `Turkify' its nation-state. The Turks were about as enthusiastic as the Orange order would be to settle in County Armagh a half million Irish Catholic evacuees. Turkish soldiers have shot refugees coming over the border or fighting for food. The Turks have on occasion arrested Kurds and threatened to send them back to Iraq where they face torture and death. Many, but not all, Turkish officials treat the Kurds with disdain.

Iran, despite endemic inefficiency and an obstructive bureaucracy that would impress the Kremlin, has welcomed Ithe Kurds and the Shi'ite Arabs from the south of Iraq — to the best of its ability. Where the Turks worried about upsetting an ethnic balance in favour of Kurds, no one in Iran complained that most of the Kurds were Sunni Muslims coming to the Shi'ite republic and that the Shi'ites were Arabs coming to Persian lands. Just the opposite. When Ramadan, that long month when faithful Muslims fast from dawn to dust, ended here on Tuesday, men sat at street corners throughout Iran to collect money, clothing and food for the refugees. To symbolise the plight of the refugees, the volunteers put canvas tents next to their little tables. By late afternoon, most of the tents were bulging with used clothes and blankets. Clear plastic bags were filled with bank notes, and metal boxes held thousands of coins. Every donor was enti- tled to a receipt. Poor workers queued to give money and an upper-class film maker told me he was collecting food, clothes and money in the wealthy neighbourhood of north Teheran. Whatever the Western world's misgivings about Iran, and there are many — particularly while Western hostages languish in Lebanon in the cus- tody of Lebanese Shi'ites under Iranian control — no one can deny Iranian gener- osity and hospitality.

Along the border I watched Pasdaran, the Revolutionary Guards who are much despised in some corners here and else- where for their fanaticism, protecting the Kurds who crossed into the country. They led them to camps behind the border and gave them tents and food. The Kurds' problems come, not from the intentions of the Iranians, but from the bureaucracy that requires permissions from a dozen officials for any relief shipment to reach its destina- tion, as well as from earth roads too narrow to permit traffic in two directions at once. Consequently, trucks carrying re- fugees away from the border block relief trucks heading in with food and supplies. Sometimes, in their enthusiasm and lack of co-ordination, the Iranians simply throw food from the back of lorries to hungry refugees who are forced to crowd one another to catch loaves of bread and bags of fruit.

Iranians are permitting Kurdish men, once they have established their families in camps here, to return to Iraq to fight against Saddam Hussein. The Teheran Times quoted the Iranian President, Ali Akbar Hasemi Rafsanjani's denial of Iraq's charge that Iran was interfering in Iraq's internal affairs, including Rafsan- jani's address to Saddam: 'It is true that the oppressed Iraqis who are in Iran have crossed the 1200 kilometer border and launched a campaign against you. But we are not responsible for this. We are not responsible for protecting your borders.' From here, the Kurds are re-launching their war against the Iraqi government, hiding in the mountains, making guerrilla attacks on the army and asking the world for better weapons with which to face Iraqi tanks and helicopters. So far, the world has offered them less of what their families need merely to survive, than it has the Kurds in Turkey — and no weapons at all.

The Kurds, like many other people in this part of the world, are victims of the enmity between the United States and Iran. It was fear of Iranian influence in Baghdad that caused the United States to allow Saddam Hussein to deploy his heli- copters against the Kurdish and Shi'ite rebellions. It is fear of helping Iran that compels the United States to limit its aid to the refugees in Turkey. Since Iranian students seized the American embassy here in 1979 the United States has not forgiven Iran any more than it has Viet- nam. Just as the Cambodians have had to pay the price for American policy that supports the Khmer Rouge coalition in order to 'contain' Vietnam, so the Iraqi refugees are suffering from the American policy of 'containing' Iran. The Kurds became refugees in the first place after the United States encouraged them to rebel and then denied them a consistent policy on the use of Iraqi air power against them. Now, those who have come to Iran instead of Turkey are suffering, and dying, for lack of international assistance. Still the Ira- nians may provide more to the Kurds from a pauper's purse than the Turks ever will from the Western world's cornucopia. The Iranians at least are leaving them their pride.

Previous page

Previous page