Afterthought

By ALAN BRIEN

RELUCTANTLY. I am coming to the conclusion that be- d ing a professional critic of anything may be an un- natural occupation. I would rather not admit this as I have spent the last twelve years being paid to sit on the bench and hand down judgment in one court or another. I have been film critic of the Evening Stan- dard, television critic of the Observer, book re- viewer for several magazines, and theatre critic since 1958, first for this paper and then, since 1961, for the Sunday Telet;raph. The critic him- self rarely recognises any sense of alienation (the vogue word of 1965) so lone as he remains in his "'n department. Just as a soldier does not notice that he is being brave or a sewerman that he is getting ,dirty, so a drama critic in the theatre assumes that it is normal to be critical. When he goes to a citiema on his evcnirg off, he feels like a' minor royalty travelling incognito. He finds he has forgotten that it costs money to get in and he is often amazed to learn that some film that should have sunk under a broadside of bad re- views has queues round the block while another Which was hailed in all the best papers as a Masterpiece is unreeling to a scattered audience of lonely sex maniacs and old ladies secretively eating out of large, noisy paper bags. For the first twenty minutes, he feels acutely uncomfortable about being so relaxed and com- fortable. Ought he not to be making notes? Should he not have read the book of the film or seen the earlier version made by Renoir in Holly- Wood in 1943? Wasn't there a long scholarly piece in Sight and. Sound explaining that the director had been sacked halfway through and his rushes re-edited by the son-in-law of the head of the studio? And above all, the nagging question--what on earth am I going to say about a. after it is over? It takes me, anyway, half art hour of brainwashing before I can convince my- self that I am on holiday in the cinema. I can snooze, make jokes, go out and buy slabs of chocolate in the foyer, move my seat, mix up all the characters' and leave before the end, without betraying any sacred trust.

A wave of heady euphoria then succeeds the bilious tension. I do not have to say anything at all about this film, to anybody, ever. I am an entirely anonymous customer. The next half-hour I give everybody involved in the enterprise the benefit of the doubt--I accept the intention for the deed. And when I leave I have reverted to the bovine level of the average fan with a critical vocabulary which consists only of a few phrases like 'a bit far-fetched,' or 'rather king drawn out,' or 'it passed the time.' Because- I have not been working, 'absorbing and recording with eye and ear an experience which must then be processed in the mind and regurgitated in' words onto a typewriter, the film has gone through me like a tomato seed without changing me or it.

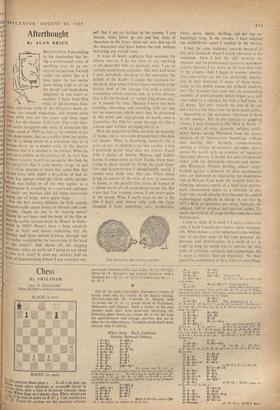

With the majority-of films (as with the majority of boas, plays, television programmes) this does not matter. What is disturbing, however, for a critic of one art dipping a toe into another. I find I positively prefer what does not matter. Faced with a choice of Jeanne Moreau and Sophia Loren, I compromise on Jane Fonda, Even now, trying to abase myself by listing the great direc- tors and screen-writers I shamefacedly avoid, I cannot even think who they are. Films about dying of cancer, or the evils of war, or peasants in Japan, or the parallel life stories of women in a labour ward..are all noted down on my list. But when that free evening comes, I am never quite in the mood. What I really want to see is the film I have seen before only with the faces changed. I want something safe, predictable, Tin dreadin,I,, the mating season.'

lively, quick, funny, thrilling and not too ex- haustingly long. In the cinema, I have adopted the middlebrow tastes I combat in the theatre.

I find the same tendency towards betrayal of my own standards when I watch television at the weekends. Here I feel the split between the amateur and the professional spectator even more acutely. because 1 sec more on the box than I do in the cinema. And I begin to wonder whether television critics are not too snobbishly intellec- tual in their dismissal of many of those ironic, camp serials which amuse me without insulting me. The rotors last year was an outstanding example of entertainment which began as a cult and ended as a runaway hit with a bull's-eye on all brows. Yet only towards the end of its run did it earn a few lines from the posh paper critics.

According to- the reviewers, television is. dead in the summer. Yet, in my capacity as goggling viewer, I look forward to The Men in Room /7 with its pair of catty, donnish, ruthless intelli- gence bosses saving Whitehall from the conse- quences of its bureaucratic bumblings without ever leaving their hermetic common-room, moving a variety of eccentric part-time agen's across the world with an armoury of ingenious electronic devices. I would not miss Undermind either with the deliciously nervous .and vulner- able Rosemary Nichols battling almost single- handed against a network of alien psychopaths who are dedicated' to sabotaging the modernisa- tion of Britain. (Last week she stopped them dis- tributing advance copies of a high-level govern- ment examination paper to a selection of dul- . lards who would thereby have become the addled technological eggheads in charge of our fate by 1975.) Both programmes are witty, fantastic, in- telligent, full of in-jokes and satirical asides, far above the level of all stage thrillers and most film melodramas.

Come to think of it, even if I were a television critic, I hope I would give them a cheer occasion- ally. What makes a critic unnatural is his willing- ness to sacrifice some of hiS own personal im- mersion. and identification, in a work of art in order to keep his hands free to operate the twin tools of criticism—analysis and comparison. He is more a martyr than an inquisitor. No man should be condemned to be a critic of everything.

Previous page

Previous page