COMPETITION

Late correction

Jaspistos

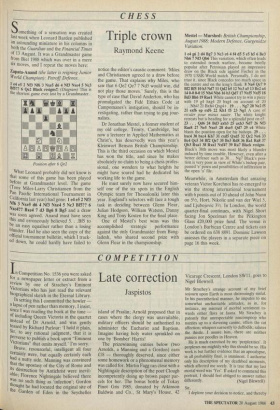

In Competition No. 1536 you were asked for a newspaper letter or extract from a review by one of Strachey's Eminent Victorians who has just read the relevant biographical sketch in the Eternal Library. In setting this I committed the howler — a lapse of pen rather than memory, I insist, since I was reading the book at the time — pf Including Queen Victoria in the quartet instead of Dr Arnold, and was gently teased by Richard Parlour: 'I hold it plain, Sir, to any rational judgment, that it is perverse to publish a book upon "Eminent Victorians" that omits myself.' I'm sorry. Brave, resourceful, intelligent all four certainly were, but equally certainly each had a nutty side. Manning was convinced that the apostasy of the City of Rome and its destruction by Antichrist were inevit- able; Florence Nightingale believed there was no such thing as 'infection% Gordon thought he had located the original site of the Garden of Eden in the Seychelles island of Praslin; Arnold proposed that in cases where the clergy was unavailable, military officers should be authorised to administer the Eucharist and Baptism. Imagine having holy water sprinkled on one by 'Bomber' Harris!

The prizewinning entries below (two Arnolds, a Manning and a Gordon) earn £18 — thoroughly deserved, since either some homework or a phenomenal memory was called for. Martin Fagg ran close with a Nightingale description of the poet Clough incompetently doing up brown paper par- cels for her. The bonus bottle of Tokay Pinot Gris 1985, donated by Atkinson Baldwin and Co., St Mary's House, 42 Vicarage Crescent, London SW11, goes to Nigel Blewrell.

Mr Strachey's strange account of my brief sojourn upon Earth is most distressingly sinful. In his parenthetical manner, he imputes to me somewhat uncharitable attitudes, as in, for instance, my mistrust of morbid sentiment to- wards either flora or fauna. Mr Strachey is patently that unrespectable nincompoop who nuzzles up to a slavering canine; offers the cat affection; whispers earnestly to daffodils; salutes the thistle. I assure him, there are neither pansies nor poodles in Heaven. He is much exercised by my 'perplexities'. It perplexes me mightily why this should be so. His work is but further evidence that an apocalypse, in all probability final, is imminent. I authorise only his description of my deathbed moments, which affected me sorely. It is true that my last mortal word was 'Yes'. If asked to commend this portrait, I should feel obliged to answer rather differently. (Nigel Blewrell) Sir, I deplore your decision to notice, and thereby

lend respectability to, Mr Strachey's Eminent Victorians. I would not complain of — nay, I would rejoice in — an open adversary; but Mr Strachey's is the arrow that flieth by night. For example:

. . everything about him denoted energy, earnestness and the best intentions. His legs, perhaps, were shorter than they should have been, but the sturdy frame . .

The cowardly art of the literary sneer stands revealed. 'Earnestness' and 'best intentions' surely virtues in a Christian society — are accompanied by a snigger under the desk. The final gibe is cast in the very act of retreat.

I will not be drawn into counter-abuse of Mr Strachey; certainly, I will not seek to suborn his tailor into revealing his inside-leg measurement. Suffice it to say that the Rugby system was created to combat precisely such moral degen- eracy as his. (Noel Petty)

The account of myself in Eminent Victorians is well written, well researched and well nigh intolerable. One must admire the author's skill in seeking to bring discredit on both Rome and Canterbury; as to his motives, one can only guess. A picture of worldliness, intrigue, spite

and dishonesty is presented. My audience with His Holiness when I visited Rome is used to accuse me of ensuring a glittering career for myself should I convert. The author is totally in error in this conjecture.

Much space is given to Newman, who emerges from this account as a saint and martyr, whereas he was a vain and foolish old man. It is wrong to suggest, as Strachey does, that I was part of a conspiracy to render him powerless, and that I was motivated by jealousy. My concern was purely the general good of English Catholics; Newman's ruin was a self-inflicted wound.

The overall picture presented of myself is of a ruthless and ambitious man, touched with vil- lainy. My God has judged me differently.

(Ronald D. Codlin) Sir, I note that Colonel de Pouncey has, in your columns, arraigned Mr Strachey as 'an emaci- ated cur' for insinuating, `while not being man enough to assert', that I was, in Equatoria, a slave of alcohol. The good Colonel adds that, had Mr Strachey been a fellow-cadet of mine at Woolwich, I should have kicked him downstairs.

Grateful as I am for this comradely interven- tion, I write to assure Mr Strachey that I should, in that unlikely coincidence, have done nothing of the kind. In writing of me as he did, he was as much the helpless vassal of the will of that Inscrutable He who determines even the very least of our actions and impulses as I was when indulging in those bouts of intemperance which he was fully justified in bringing to the attention of his readers.

Mr Strachey will, I trust, join me in a genial b. and s. if he eventually arrives here.

(Andrew McEvoy)

Previous page

Previous page