No Gunfire

THIS year might have been the end of the beginning for the Liberals; instead, it has been the beginning of the end. The Liberal candi- date lost his deposit at Dumfries; and, only the week before, the two other Liberal candidates at St. Marylebone and Sudbury both came within a fraction of one per cent of losing theirs. It was always probable that, when the time came for the electors to make a real political choice, the Liberal revival in the constituencies would collapse. But it is none the less noteworthy.

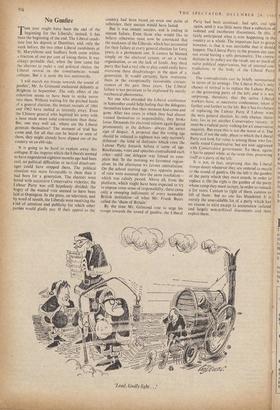

'I will march my troops towards the sound of gunfire', Mr. Jo Grimond exclaimed defiantly at Brighton in September. The only effect of the exhortion seems to have been to strike terror into them. Without waiting for the pitched battle of a general election, the instant recruits of 1961 and 1962 have melted as instantly away. Even the Chinese general who baptised his army with a hose made more solid conversions than these. But, one may well ask, where are the Liberal generals themselves? The moment of trial has come and, for all that can be heard or seen of them, they might already have slipped out of the country on an ebb tide.

It is going to be hard to explain away this collapse. If the impetus which the Liberals seemed to have engendered eighteen months ago had been real, no political difficulties or tactical disadvant- ages could have stopped them. The political situation was more favourable to them than it had been for a generation. The electors were bored with successive Conservative victories; the Labour Party was still hopelessly divided; the bogey of the wasted vote seemed to have been laid at Orpington. In the press, on television, and by word of mouth, the Liberals were receiving the kind of attention and publicity for which other parties would gladly pay. If their appeal to the country had been based. on even one point of substance, their success would have lasted.

But it was instant success, and is ending in instant failure. Even. those who would like to believe otherwise must now be convinced that the weakness of the Liberals, which has accounted for their failure at every general election for forty years, is a permanent one. • It cannot be blamed simply on the electoral system, or on a weak organisation, or on the lack of funds. Any third party that had a real role to play could easily have overcome these disadvantages in the span of a generation. It would certainly have overcome them in the exceptionally favourable circum- stances of the past three years. The Liberal failure is too persistent to be explained by merely mechanical phenomena.

No one who attended the Liberal conference in September could help feeling that the delegates themselves knew that their moment had come and gone. After two years in which they had almost trained themselves to responsibility, they broke loose. Demands for electoral reform again figured prominently in the debates--always the surest sign of despair. A proposal that the voting age shoUld be reduced to eighteen was only narrowly defeated—the kind of dottiness which even the Labour Party forsook before it came of age. Resolutions, votes and speeches contradicted each other—until • one delegate was forced to com- plain that in the morning we favoured region- alism. In the afternoon we favour centralistion,' On the school starting age, two opposite points of view were assumed into the same resolution— which was calmly passed. Above all, from the platform, which might have been expected to try to impose some sense of responsibility, there came only a sweeping indictment of every nameable British institution—of what Mr. Frank Byers called the 'sham of Britain.'

By the time Mr. Grimond rose to urge his troops towards the sound of gunfire, the Liberal

Party had been atomised: had split, and split again, until it was little more than a collection of isolated and . incoherent discontents. In this, it r fairly anticipated what is now happening in the country as a whole. The important fact to grasp. however, is that it was inevitable that it should 1: happen. The Liberal Party in the present day can- a not avoid having a split personality. The contra- dictions in its policy are the result, not so much of naïve political opportunism, but of internal con- tradictions in the body of the Liberal Party itself.

The contradictions can he briefly summarised in terms of its strategy. The Liberal Party's only chance of revival is to replace the Labour Party a'; the governing party of the left; and it is not surprising, therefore. that the active Liberal workers have, at successive conferences, taken it farther and farther to the left. But it has no chance of replacing the Labour Party if Labour ■% ins the nem general election. Its only chance. there- fore, lies in yet another Conservative victory : it must be a radical party wishing fora Conservative majority. But evert this is not the worst of it. The natural, if not the only. place to which the Liberal Party can look for votes is among:those who for- merly voted Conservative, but are now aggrieved with Conservative government. To these, again, it has to appeal while. at the same time. presenting itself as a party of the left.

It is not, in fact, surprising that the Liberal troops desert whenever they arc ordered to march to the sound of gunfire. On the left is the gunfire of the party which they must smash, in order to replace it. On the right is the gunfire of the party whose camp they must occupy, in order to ransack it for votes. Cannon to right of them, cannon to left of them : but no one has blundered. It is merely the unavoidable lo[ of a party which has no reason to exist except to accumulate isolated and largely non-political discontents and then exploit them.

f.

s, it ti it v

c, tl 0 '1

a d rr 0 r(

IT

it ft st L pt

'Lead, kindly light .

Previous page

Previous page