TOPICS OF THE DAY.

LEAGUES TO ENFORCE PEACE.

THE Allies' Reply to Mr. Wilson's Note is not only a very able but a very wisely and happily worded document. In no particular is it more happy than in the clause which deals with Mr. Wilson's proposals for creating a League to. Enforce Peace. It sets up no aggressive non possumus, to the Presi- dent's favourite scheme, but, unless we are greatly mistaken, tries to lead him gently by the hand away from the point of danger, and to turn the steps of all good-intentioned and pacific-minded people in a safer direction. In Clause II. of the Reply the Allies declare that they associate themselves whole-heartedly with the plan of creating a League of the Nations to ensure peace and justice throughout the world, and they then go on to say that they recognize all the advan- tages that would accrue to the cause of humanity and civiliza- tion " by • the establishment of international settlements designed to avoid violent conflicts between the nations— settlements which ought to be attended by the sanctions necessary to assure their execution, and thus to prevent fresh aggressions from being made easier by an apparent security." At first sight it may seem as if this passage proves that the Allies are willing to .accept the proposals of Mr. Wilson and his fellow-citizens in regard to a League to Enforce. Peace. If we look a little closer, however, we shall see that the words we have quoted avoid, or at any rate have the appearance of being drafted so as to avoid, the dangers to liberty and justice inherent in such a League, dangers which we have so often insisted on in these columns. Not only are the words " to enforce peace " left out, but the words substituted point to the League being one of generous aspirations rather than of hard-and-fast military and naval ConVentions. Further, the phrases about international settlements seem to show that more effort is to be spent upon setting Europe Upon a sound foundation at the peace, and of establishing, for the time at any rate, a satisfactory status quo, than upon plans for petrifying that status quo when established. It is true that words of an ambiguous, and therefore possibly dangerous, character follow in regard to " sanctions,' but they, we ex- pect, were due more to politeness to Mr. Wilson and a desire not to hurt the feelings of the Pacificists of the United States than to any other cause. In any case, it is impossible to claim the Note as an acceptance of the principles of the League to Enforce Peace.

We shall be asked, no doubt, why we are so strongly opposed to the League to Enforce Peace. Our answer is that we believe such a League must, if established on the lines of the organiza- tion already in existence in America, interfere with the principles of humanity and justice. If successful, it must mean the " embalming " or petrifaction of the status quo at the time 'the League was made, and thus in future years prevent development and growth in international relations. Farther, it muse give • opportunities to selfish and ambitious statesmen or communities to manipulate the nomi- nal principles, machinery, and general power of the League to their own advantage, and in such a way as to deprive other communities of their independence: If we are asked what ground we have for taking so gloomy a view Of what is likely to be the outcome of an International League to Enforce Peace, our answer is to point to the attempt made after the last great war in which not merely two or three Powers but practically all the Powers of Europe were involved. The Napoleonic Wars ended in the Holy Alliance, and the Holy Alliance was founded quite honestly and for exactly the same _ reasons. that Mr. Wilson and Mr. Taft and their friends seek to establish the League to Enforce Peace. It was founded on a horror of war caused, and naturally caused, by the fierce struggle which began in 1792 and ended in 1815. -Again, it was founded with a genuine desire to further the welfare of the peoples of Europe, and in the interests of suffering humanity.

No doubt it did something to keep the peace in Europe, though that peace would probably have been kept without it owing to the condition of exhaustion in which Europe then found itself. Yet instead of helping the peoples and furthering the cause of justice and humanity, it had the very opposite effect and came the main prop of tyranny and injustice. To this statement it will no doubt be objected, by those who have not made a study of what happened between the years 1815.1835, that we have no right to say that the League to Enforce Peace would fail because the Holy Alliance failed. Failure is not necessarily a proof of badness in human institutions. We agree, and we should be the last people to arraign a scheme framed with the admirable main object of the Holy Alliance, merely because it failed. Our objections and our use of the failure of the Holy Alliance as an argument against setting up a League to Enforce Peace rest on very different grounds. In all we have said on the subject we have always sought to show, and we believe have shown, that the Holy Alliance failed, not because of any fault in its object, and not because of any bad intentions on the part of those who created it or originally handled it, but because of defects in the system created—defects inherent in the machinery adopted by the Alliance to further its great project. These very same defects exist in the proposal for carrying out the objects of the League to Enforce Peace.

We can find then no better method of substantiating our view than by reminding our readers once again- of the way in which the Holy Alliance came into existence, and of how rapidly it degenerated from its high peace ideals into a League for the enforcement of the status quo—i.e., a League for knocking on the head any move- ment for the development of human liberty. William Pitt and the young Emperor Alexander in 1804 must be said to have been the originators of the Holy Alliance. When Pitt was proposing to Alexander to join the third Coalition for carrying on the war against France, the English statesman declared that one of the three essential objects of that Coalition was the establishment of "a convention and guarantee for the mutual protection and security of the different Powers, and the establishment in Europe of a general system of public law." He then went on to draw up a scheme which almost exactly corresponds•with the proposal of the League to Enforce Peace, set forth by Mr. Taft's organization or described by Mr. Wilson in his speeches :-- "Much," he says, "will have been done for the repose of Europe by the carrying out of the proposed territorial rearrangements, but in order to make this security as perfect as possible, it seems necessary that at the time of the general pacification a treaty should be concluded, in which all the principal European Powers should take part, by which their possessions and their respective rights, as then established, should be fixed and recognized ; and these Powers should all engage reciprocally to protect and support each other against all attempts to violate it. This treaty would give to Europe a general system of public law, and would aim at 'repressing, as far as possible, future attempts to trouble the general tranquillity, and above all to defeat every project of aggran- dizement and ambition, such as those which have produced all the disasters by which Europe has been afflicted since the unhappy era of the French Revolution." The first "separate and secret" article of the Treaty of April 11th, 1805, between Russia and. Great Britain embodied these views in a formal engagement. " Their Majesties," it ran, " who take the most lively interest in the discussion and precise definition of the law of nations and in the guarantee of its observance by general consent and by the establishment in Europe of a federative system, to:ensure the independence of the weaker States by erecting a formidable barrier against the ambition of the more powerful, will come to an amicable understanding among themselves as to whatever may concern these objects, and will form an intimate union for the purpose of realizing their happy effects."

It may be remembered that Mr. Wilson looked forward to " a universal association of nations to maintain inviolate the security of the highway of the seas for the common unhindered use of all the nations of the world, and to prevent any war begun either contrary to treaty covenants or without warning and fall submission of the cause to the opinion of the world— a virtual guarantee of territorial integrity and political inde- pendence."

However, that is not the point for the moment. Pitt's words appear to have sunk very deeply into Alexander's. mind, and after his long flirtation with Napoleon and subsequent quarrel, he returned in 1815—i.e., when the war was over—to his first love, peace and a federative League to enforce it. With an ardour in favour of popular rights and humanity which we are sure was not feigned but for the moment very real, and with a deep hatred of war, the Emperor Alexander established the Holy Alliance or nineteenth-century League to Enforce Peace. The British Government then, as now, were a little shy of the proposition from the beginning, but very properly did not like to reject it at once for fear of being misunderstood. Accordingly they at first seemed willing to join with the promoters of the scheme. When, however, the Holy Alliance got to business, as it did in the Conference at Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818, our wise and, in the truest and best sense, liberal statesmen began to be alarmed at the lines on which the League was developing. Castlereagh in a most admirable and most tactful memorandum addressed to the Emperor Alexander tried to dissuade him from pushing on his scheme, and to suggest a via media between the two extremes of making no effort to ensure peace and the appalling proposal for stereo- typing the status quo and rendering it impossible for any mis- governed State or portion of a State to free itself from those who maltreated it—a proposal for making the wide world, in (Continued on page 62.)

THE LEAGUE TO ENFORCE PEACE.

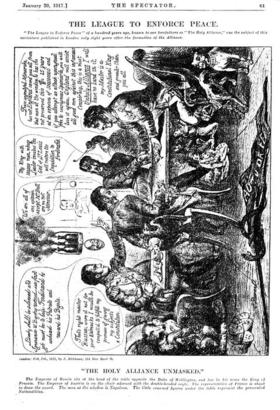

"The League to Enforce Peace" of a hundred years ago, known to our forefathers as "The Holy Alliance," was the subject of this caricature published in London only eight years after the formation of the Alliance.

"THE HOLY ALLIANCE UNMASKED."

The Emperor. of Russia sits at the head of the table opposite the Duke of Wellington, and has in his arms the King cf Prussia. The Emperor of Austria is on the chair adorned with the double-headed eagle. The representative of France is about to draw the sword. The man at the window is Napoleon. The little crowned figures under the table represent the persecuted Nationalities. (Continued from p. 60.) Gibbon's words, but " a safe and dreary prison house " for tho foes of any member Of the Alliance. Here are Castle: reaghis actual words The problem of a Universal Alliance for the peace and happiness of the world," the memorandum runs, "has always been one of speculation and hope, but it has never yet been reduced to practice, and if an opinion may be hazarded from its difficulty, it never can. But you may in practice approach towards it, and perhaps the design has never been so far realized as in the last four years. During that eventful period the Quadruple Alliance, formed upon principles altogether limited, has had, from the presence of the sovereigns and the unparalleled unity of design with which the Cabinets have acted; the power of travelling so far out of the sphere of their immediate and primitive obligations, without at the same time transgressing any of the laws of nations or failing in the delicacy which they owe to the rights of other States, as to form more extended alliances . . . to interpose their good offices for the settlement of differences between other States, to take the initiative in watching over the peace of Europe, and finally in securing the execution of its treaties. The idea of an Alliance Solidaire, by which each State shall be bound to support the state of succession, government, and possession within all other States from violence and attack, upon condition of receiving for itself a similar gua tee, must be understood as morally implying the previous establishment of such a system of general government as may secure and enforce upon all kings and nations, an internal system of peace and justice. Till the mode of constructing such a system shall be devised, the consequence is inadmissible, as nothing would be more immoral or more prejudicial to the character of government generally, than the idea that their force was collectively to be prostituted to the support of established' power, without any consideration of the extent to which it was abused: Till a system of administering Europe by a general alliance of all its States can he reduced to some practical form, all notions of a general and unqualified guarantee must be abandoned, and the States must be left to-rely for their security upon the justice and wisdom of their respective systems, and the aid of other States according to the law of nations."

It would be impossible for us to summarize our objections to the League to Enforce Peace better than in these wise and moderate terms. The only valid criticism which, as far as we can see, could be raised in regard to Castlereagh's grave caveat against entering into relations- with other States of a kind which might end in guaranteeing ' the negation of God erected into a system,' is the criticism that there is no reason why States should not league themselves to enforce peace without at the same time pledging themselves not to interfere with each other's domestic concerns, or at any rate without promising to go to each other's assistance if their internal stability were to be threatened. The answer to the first part of the objection is that if the Powers were .allowed to interfere in each other's domestic affairs—i.e., to help one part of a nation against another part—yoa would be leaving vast causes of war still open. America made war upon Spain because the people of the United States held, rightly as we think, that Spain had treated Cuba badly. If the United States were to bind herself in future never to interfere again on similar lines in the case of any European or Eastern State (Japan and China- must be parties to a League to Enforce Peace), who can deny that one of the guarantees for freedom and humanity would have been withdrawn 1 Even if the people of the United States were willing to bind themselves in this way, which we refuse to believe possible if the matter were properly explained to them, the British people would not be willing. Things might very well go on in the Far East which it would be quite impossible for-us to tolerate. Again, some aggressive revolutionary move- ment like that of the French Revolution might overthrow the existing government in a particular State, and so upset the equilibrium of the League. This position may perhaps be condemned as one of finding niggling faults. The main objection to what Pitt in his separate and secret article of the Treaty of 1805 with Russia called the establishment of a federative system is, as Castlereagh saw, that it must by its very nature interfere with the independence of existing Governments. As we said long before the war, you can have universal peace at ,a price. But that price is the amender of a large share of independence and freedom. In our opinion, that price is too high. `While dealing with the subject of the League to Enforce Peace we should like to draw attention to the illustration on the previous page. It is a reproduction of a Liberal caricature entitled " The Holy Alliance Unmasked, "published in London in the year 1823—that is, only eight years after the for- ination of this well-intentioned League to enforce peace. It is very interesting to see the part Wellington plays in the caricature. Instead of being represented, as one might have expected, as the arch-Tory and enemy of liberty, he appears among the banded monarchs of Europe as the Liberal statesman 1 It will be seen that the idea which in 1815 was supposed to be fundamental—the idea of avoiding war and protecting the peoples from its horrors—had died out. The thought of the four monarchs represented is merely how to combine to crush the slightest movement among the sub-nationalities over whom they- are the masters. Beneath- the ,table and under their feet are the little kingdoms. Note that the British bulldogs. Justice and Honesty, are tightly muzzled, and that the flag of the Inquisition-is in the foreground. Oddly enough, the attempt of the Holy Alliance to carry out its promises and help Spain to prevent the revolt of her American colonies is not mentioned, though it was that attempt -which .exasperated British public opinion, and soon led, as our readers know, to the establishment of the Monroe Doctrine and to the protest of the President of the United States against what he alluded to in his Message as " their system," " their," as the context shows, meaning that of the European Sovereigns who formed the Alliance. Certainly history has no greater example of irony than that the League to prevent the horrors of war should in eight or nine years be running the risks of carrying ,war into the American Continent, which had escaped all the dangers of the Napoleonic period, and o f forcing theUnited States to take up arms in defence of what she deemed to be a menace to her freedom and independence. The caricature, however, speaks for itself. Once again let us warn our readers not to think that the Holy Alliance was when it began what it cer- tainly was when it ended—a menace to human liberty and an engine of war and oppression. Alexander, though his views wore visionary, was perfectly honest in his intense hatred of war, and in his desire to establish some system for preventing it. We cannot put it higher than by saying that he was quite as strong a Pacificist as Mr. Wilson or Mr. Taft or any of their supporters, if not a stronger. Nor was he a hater of liberty in the abstract, for it must be remembered that it was he who insisted that when the Bourbons were restored France should have a fairly liberal Constitution. The Bourbons, indeed, hated him as a dangerous Radical visionary. But though we feel obliged to put up the danger-signal which we have hoisted in regard to Leagues to Enforce Peace, it must not be supposed that we consider nothing can be done for the cause of peace in the future. There are, in our opinion, useful methods, though not nearly so sensational, for helping the cause of peace. But these cannot be discussed now. We hope to return to them, however, on a future occasion.

Previous page

Previous page