WARM FUZZIES FOR EVERYONE

It is not just Mr Blair's stakeholding that is wrong for Britain; it is Mr Blair

himself says Bruce Anderson • . . I didn't work the things out very clearly at the time, but they were influences that stayed with me.'

They certainly have; they underlie all his recent statements on the stakeholder economy. Mr Blair clear- ly believes that Macmurray has guid- ed him to his Big Idea, or 'unifying concept and theme', as he would pre- fer to call it. So should we accept his claim? One point is not in doubt. Macmurray had big ideas. He thought that philosophy should address itself to the great questions instead of verbal quibbles, which is why his fellow philosophers disregarded his work. Tony Blair is correct in describing his men- tor as a philosopher of the human condition. That condition is not in good shape at the moment. As we approach the end of the least successful century in human histo- ry for about 1,500 years, there are no grounds for optimism. Within a couple of decades, terrorist states — and groups will almost certainly be in possession of nuclear and biological weapons; the odds must be against the survival of the human race for another century. But even if we avoid destruction, can our Western civilisa- tion outlast the collapse of its two main buttresses: religion and scarcity? Until a couple of hundred years ago, the existence of almost all human beings was merely a slightly more technologically sophisticated version of the animal contest with nature in the struggle for food, warmth, shelter and sex. Human life was menaced by hunger, disease and oppres- sion. All societies were coercive. Then came the industrial revolution, free mar- kets and Enlightenment liberalism. At least in the advanced West, man seemed to have made a decisive break with the miseries of his previous history: no more scarcity, no more tyrants — no more God, except per- haps as a neutered, constitutional-monarch form of deity. Mankind could look ahead to a Promethean destiny.

To which Macmurray and the other Enlightenment sceptics had a simple response: poor fools, poor deluded fools. You think you can conquer nature; you will never conquer your own nature. You think that you can do without God; very well, you can make do with the devil. If you try to emulate Prometheus, you will suffer Prometheus's fate. Like Burke and de Maistre, Macmurray believed that unless society is founded on religion, their labour is lost that build it.

Lost labour brings us back to new Labour and to Mr Blair. Inasmuch as it can still snarl, or whimper, the beaten-dog wing of the Labour Party — it used to be called the Left — disapproves of Macmurray. They would rather their Leader's reading was more overtly socialist; which makes them another set of deluded fools.

Macmurray was a socialist, in any sensi- ble use of the word. He not only translated Marx; the early Marx was one of the main influences on his thinking. Macmurrayism was little more than early Marx plus Chris- tianity: an easy fusion. Like the young Marx, Macmurray believed that man had alienated his labour and made a fetish of commodities. Getting and spending we lay waste our powers: only by reconstructing society as a series of post- capitalist, egalitarian communi- ties could we avoid the current waste of human potential and achieve social cohesion.

There is much force in Mac- murray's criticism of capitalism: it is destabilising. By undermin- ing traditional societies, based on the hierarchies of age and sta- tus, it also destroys the social cohesion which those societies could achieve. It does turn men into adjuncts of machines and computers: discontented adjuncts at that. For capitalism creates wants which human life can never satisfy. It may eradicate primae- val scarcity, but it inspires new scarcities in the midst of afflu- ence. The ensuing discontents fuel disorder and crime.

Though it is not true that capitalism is incompatible with religion or family life, they are awkward companions; capitalist society has a constant tendency to substi- tute desires for disciplines. So if we are to remain capitalist, we will have to remember one of Isaiah Berlin's favourite phrases from Kant: 'All the great goods cannot live together.' Under capitalism, we will never be able to achieve the full flowering of Enlightenment libertarianism. The anar- chic element in capitalism will always require the constable to contain it.

Given all this, it is surprising that the moral and aesthetic anti-capitalism of early Marx is not a more potent political force. It should be easy to argue that the riches of technology have made young-Marxism more attainable, just as a century of war and social breakdown have made it more desirable. Though a Macmurrayite Labour Party might not find it easy to win elec- tions, it would have a formidable intellectu- al and moral position.

Unlike Tony Blair. Mr Blair is not a Macmurrayite. He told one interviewer: 'If you really want to understand what I'm all about, you have to take a look at a guy called John Macmurray. It's all in there.' All of Blair may be on the lower slopes of Macmurray; there is little of Macmurray in Blair. If Mr Blair does not know this, he is not bright enough to be a curate in the Church of England. But he must know it, which makes him a worthy successor of Harold Wilson and an apt pupil of Peter Mandelson. Tony Blair may have been a Macmurrayite in his left-wing youth, but all that survives today are some half-remem- bered undergraduate discussions, a few phrases for his speeches and an idealistic gloss for his rhetoric. As a reading of his stakeholder speech and his Frost interview makes clear, his position has no substance whatsoever.

He tells us that everyone should have a stake in society: we do already. The poorest he who sleeps on the streets at least has a street to sleep on. So what is this new stake which Mr Blair is offering? Is it a right, enforceable at law? Is it an asset, sellable in the marketplace? It does not seem to be any of that, according to the answers he gave to David Frost. Its more of, er, um . . . an aspiration, a vision. 'You can call it, if you like . . . a slogan.' We do like, Tony, and we will. 'What is [this] stake in the new stake-holder society other than warm fuzzies?' asked Sir David. What indeed? What is Tony Blair other than a warm fuzzy?

It would be possible to give the term stakeholder some meaning, and Professor David Marquand has tried to do so. He writes: 'It is opening the door to a left-of- centre project for government more radical than anything attempted in this century in modern times . . . the notion . . . would imply, at the very least, radical changes in company law [and] radical changes in industrial relations.' The Professor recently rejoined the Labour Party after a number of years in the SDP, but he has not caught up with the changes that have occurred while he was away. That word 'radical', for instance: a bad example of Oldspeak. You will not find it in Spin and Sound, Peter Mandelson's vocabulary book for aspiring fuzzies. Nor will you find 'industrial rela- tions.'

If David Marquand wants to learn how to do it, he should study the Frost tran- script. At one stage, Mr Blair says that he is against unemployment (gosh). So you are going to give everyone a job, then, said Sir David. How long will that take? Oh, you can't possibly expect me to answer ques- tions like that, replied the Fuzzy, but I am against unemployment, I really am.

Sir David might have asked him how his proposals on the social chapter and the minimum wage would help to reduce unemployment. He might also have men- tioned the high levels of youth unemploy- ment in France and Spain, brought about by the policies Labour wishes to copy. But even if the question had been put, Mr Mandelson would no doubt have given his Leader advance briefing on how to fuzz it.

In another classic fuzzyism, Mr Blair told Sir David: 'There are people in work at the moment who don't get the prospects that they want, whose ambitions are thwarted, and we've got to be enabling them to do better.' Those comments could apply to almost everyone at some stage in their career. 'Thwarted ambition' certainly describes Tony Blair at the moment, and all his colleagues. So if he wins the next election, he will be able to claim to have honoured his pledge, in that some hun- dreds of persons' ambitions will instantly be unthwarted. The rest of the population will get a warm fuzzy.

`Community' in the sense that Macmur- ray used it had meaning. 'Community' in Blairfuzz is like a new recipe that someone has discovered in Tuscany which suddenly becomes all the rage, so that you cannot go to dinner in Islington without eating it and talking about it.

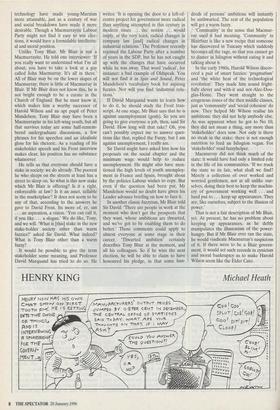

In the early 1960s, Harold Wilson discov- ered a pair of smart fuzzies: 'pragmatism' and 'the white heat of the technological revolution'. They made him sound fright- fully clever and with-it and not-Alec-Dou- glas-Home. They went straight to the erogenous zones of the then middle classes, just as 'community' and 'social cohesion' do now. They helped Mr Wilson realise his ambitions: they did not help anybody else. As was apparent when he got to No 10, they did not mean a thing, any more than `stakeholder' does now. Not only is there no steak in the stake: there is not enough nutrition to feed an Islington vegan. For `stakeholder' read fuzzyhelper.

Macmurray did not think much of the state: it would have had only a limited role in the life of his communities. 'If we track the state to its lair, what shall we find? Merely a collection of over worked and worried gentlemen, not at all unlike our- selves, doing their best to keep the machin- ery of government working well . . . and hard put to . . . keep up appearances. They are, like ourselves, subject to the illusion of power.'

That is not a fair description of Mr Blair, yet. At present, he has no problem about keeping up appearances, as he deftly manipulates the illusionism of the power- hungry. But if Mr Blair ever ran the state, he would vindicate Macmurray's suspicions of it. If there were to be a Blair govern- ment, it would set such records in cynicism and moral bankruptcy as to make Harold Wilson seem like the Elder Cato.

Previous page

Previous page