The West still declining

Bohdan Nahaylo

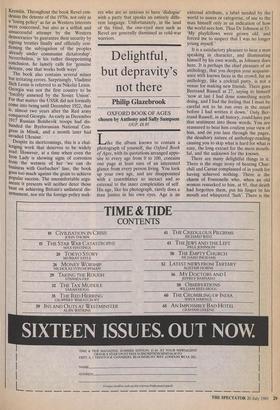

HOW DEMOCRACIES PERISH by Jean-Francois Revel

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £12.95

This is a powerful and pugnacious work, even if the subject — the West's vulnerability to the Soviet threat — is hardly a new one. Born out of Revel's anger and alarm at the West's 'amnesia and myopia' in dealing with Moscow, the book sets out to show that Western behaviour during the last decade has been character- ised by political shortsightedness, moral cowardice, and, worst of all, a debilitating sense of inferiority and guilt. Ill-equipped to withstand the relentless covert and overt pressure from its implacable totalitarian adversary, democratic society is in danger of ending up in the dustbin of history.

The author is concerned not so much with the Soviet military threat, as with the extension of Moscow's expansionist poli- cies by other means. From the very outset, he recalls, the leaders of the Soviet state have abhorred everything that the demo- cratic world represents, and have been committed to its eventual destruction and the worldwide triumph of their peculiar brand of socialism. Today the Kremlin may be more skilled in camouflaging its designs, but it nonetheless retains its sinister goal.

This is, however, something that is very difficult for people living in the West to swallow. The avowed Soviet desire to co-exist peacefully is taken at face value. While the West persists with its passive `live and let live' disposition, its ideological adversary is busy undermining Western defences by means of deception, infiltra- tion and the erosion of Western values and self-confidence. Already even the terms `capitalist' and 'bourgeois' have acquired a pejorative ring. For some, the differences between the two competing systems have become blurred, and each is regarded as equally reprehensible. The most common and dangerous assumption is that 'after all, they are really just the same as us.'

Revel urges the West to face up to the reality so as not to be duped and ultimately destroyed by a rival system that 'parades as democracy perfected when it is in fact the absolute negation of democracy.' He is concerned that even after the revelations about the Gulag Archipelago, both past and present, the fate of the Prague Spring and Poland's 'renewal', the invasion of Afghanistan and the Soviet nuclear build- up in Europe, far too many Westerners at all levels either fail to draw the appropriate conclusions, or prefer simply to look the other way. Even the warnings of Sakharov, Solzhenitsyn, and many others, who tell us what the Soviet system is like from the inside, have come to grate on our ears.

Revel believes that democracy's fate is in the balance. If it is to survive, attitudes have to be drastically altered. 'An almost total Western intellectual reconversion' has to take place in order that 'a sound understanding of what communism is and how it works' prevails. Only then will the democracies be able to close ranks, ward off the mortal threat and perhaps even outlive an enemy, who, for all his frighten- ing power, is in fact afflicted with an `intrinsic and incurable cancer'. The author knows he is asking a great deal, and concedes that the transformation is unlike- ly to occur.

But are things really as bad as Revel suggests? Certainly, the Reagan adminis- tration cannot be accused of harbouring illusions about the 'evil empire'. Conserva- tive governments are in power in Britain and West Germany. And in Revel's own native France, President Mitterrand, about whom he is too disparaging, has been much firmer in dealing with Moscow than his predecessor ever was, and was actually the first of the present Western leaders to denounce the legacy of Yalta. Is it not the case that, despite all the various stresses and strains, the Western Alliance holds together reasonably well? Washington's allies may not have supported Reagan's call for a Western boycott of the construc- tion of the Euro-Siberian gas pipeline, but when it came to something as crucial as off-setting the Soviet deployment of SS-20 missiles, they have not broken ranks and have both weathered the storm of protests by Western peace campaigners and not been swayed by the Kremlin's relentless peace offensive.

Revel's entire approach is polemical, and the problem is that he has a tendency to overstate his arguments, and after the first hundred pages begins to sound some- what repetitive. Elements of inconsistency and contradiction also creep in. At times the reader is left with the impression that the author has merely strung together a series of short, incisive essays and com- mentaries without bothering too much about the book's overall coherence.

`Democracy is less than ever threatened from within', Revel asserts on page 15, yet in the following chapter he dwells on the inherent fragility of democratic societies. He maintains that 'Monumental failure . . . will not make communistic states disintegrate or keep them from being imperialistic', but goes on to advocate the use of economic sanctions against the Kremlin. Throughout the book Revel con- demns the detente of the 1970s, not only as a 'losing policy' as far as Western interests were concerned, but also as a selfish and unsuccessful attempt by the Western democracies 'to guarantee their security by signing treaties finally and officially con- firming the subjugation of the peoples already under communist dictatorship'. Nevertheless, in his rather disappointing conclusion, he lamely calls for 'genuine detente, one that works both ways'. The book also contains several minor but irritating errors. Surprisingly, Vladimir filch Lenin is referred to as Nikolai Lenin. Georgia was not the first country to be `forcibly annexed by the Soviet Union'. For that matter the USSR did not formally Come into being until December 1922, that is, almost two years after the Red army conquered Georgia. As early as December 1917 Russian Bolshevik troops had dis- banded the Byelorussian National Con- gress in Minsk, and a month later had invaded Ukraine.

Despite its shortcomings, this is a chal- lenging work that deserves to be widely read. However, at a time when even the Iron Lady is showing signs of corrosion from the wetness of her 'we can do business with Gorbachev' line, the book goes too much against the grain to achieve Popular success. The uncomfortable argu- ments it presents will neither deter those bent on achieving Britain's unilateral dis- armament, nor stir the foreign policy mak-

ers who are so anxious to have 'dialogue' with a party that speaks an entirely diffe- rent language. Unfortunately, in the land of the blind, the one-eyed men such as Revel are generally dismissed as cold-war warriors.

Previous page

Previous page