GILBART'S HISTORY OF RANKING IN AMERICA. THIS is a well-tinted

and able volume ; containing a vast number of facts and a careful selection of opinions on the past and present condition of Banking in the United States, and on the causes of the pressure on the Money-market at home. With these the author has intermingled some suggestions as to the improvements we may make in the legal regulation of our banks by engraftings from the American system, and a defence of Joint Stock Banks against the charges of Mr. Hoestsv PALMER and other friends of the Bank of England. The fundamental difference between banking in England and in America may be resolved into two points. In America, every bank is chartered, neither private nor joint stock banks existing ; and the leading provisions of every charter granted by the State are uniform, and are drawn in compliance with the directions of an " Act to regulate Banks and Banking." In America, every char- tered bank can sue and be sued ; in England, joint stock banks within sixty-five miles of London, though sanctioned by law, have no prescribed mode of effecting this necessary business, (another point for Mr. C it ARLES NV OOD when he wishes to eulogize the grand settlement of the Bank Charter.) In America, all new banks must have paid up, in gold or silver money, fifty per cent. of their capi- tal, which pas ment must be certified after inspection by three commissioners; and shareholders are rarely responsible for more than their shares. The amount of notes issued must not be greater than ft times the amount of the paid-up capital; the total amount of a bank's liabilities (exclusive of deposits) must not ex- ceed twice the amount of its capital,--the private property of the directors being liable in case of excess, unless they give public notice of their dissent. The number of directors, the mode of their election, and other general matters relating to the manage- ment of the bank, both as between the proprietors themselves and the public, are prescribed. Annual returns are required from every bank to the public secretary, as to its condition ; and from these returns an abstract is prepared and published to show the actual condition of the currency and the state of banking in the province. The Legislature also reserves to itself the power of examining the affairs of the bank, and in certain cases of for- feiting its charter. Provision is also made for the amount of the state loans, and other public purposes of a strictly provincial nature. A tax of one half per cent. is levied on the amount of the capital of the bank; the lower class of notes must be printed from PERKINs' stereotype plate—to prevent forgeries, we presume ; and in ease of a new bank being chartered with new privileges, all existing banks are entitled to the same.

It is useless to attempt a comparison between the public regu- lations of England and of America, because in England there are no regulations at all. According to Mr. CLAYS Committee of last year.

" The law imposes on the Joint Stock Banks no preliminaty obligation, be- yond the payment of a licence-duty, and the registration of the names uf share- holders at the Stamp-office. " The law does not require that the deed of settlement shall be considered or revised by any competent authority whatever ; and no precaution is taken to enforce the insertion in such deeds of clauses the most obvious and necessary." "The law does not impose any restrictions upon the amount of capital. This will be found to vary from 5,000,0001. to 100,0001.; and, in one instance, an unlimited power is reserved of louring shares to any extent. "The law does not impose any obligation that the whole or any certain amount of shares shall be subscribed for before banking operations commence. In many instances banks have commenced their business before one half of the shares are subscribed for ; and 19,000, 20,000, and 30,000 shares are reserved to be issued at the discretion of the directors.

"The law does not enforce any rule with respect to the nominal amount of shares. These will be found to vary from 1,000/. to 51. The effects of this variation are strongly stated in the evidence. The law does not enforce any rule with respect to the amount of capital 'aid up before the commencement of business. This will be found to vary from Mi. to W."

"The House will Nee from this analysis, that these deeds of partnership, on which depend the whole transactions of the banks and their responsibility to the public, so far from being framed according to one common and uniform principle, differ materially from each other in many most important particulars; and in some instances, the deeds contain provisions open to very serious objec- tions, as entailing possible consequences highly injurious to the iutereats of the public, and of the banking establishments themselves."

As a scientific master of banking, and as the manager of one of the most respectable joint stock banks, and indeed the only one that can be said to have come into active competition with the Bank of England, Mr. GILBART'S opinions as to what modifica- tions may advantageously be adopted into the English system are entitled to great attention,--with the reservation, however, that he is not likely to he too stringent against the bunks in flivour of the public. For a practical, or even a lull acquaintance with this branch of his subject, recourse must be had to the velum! ; but we may give a general outline. In our author's view, no harm is likely to arise from the non-revisal of the joint stock deeds of settlement, as they are always drawn and inspected by high legal authorities ; but he admits it might be well to have it barrister appointed for this purpose with delined and limited powers, and a right of appeal from him to the Crown lawyers. He thinks it proper that a moderate proportion of the nominal capital of a bank should paid up; but not all, as it prevents the directors from meeting sudden difficulties by calling for further instalments upon each share,—a course which might have saved the Northern and Central Bank, could it have been adopted. To any legal direction as to the amount of a bank's real capital Mr. GI LBAILT is very averse, because it should altogether depend upon the extent of its business ; and he says that the objectors to nominal capital " are misled by words :" but if they are, it is the directors who mislead, for we have observed that whilst the nominal capital is always exhibited in large figures, the public are left to calcu- late the amount actually paid up; and sometimes in business advertisements it is omitted altogether. To the American system of regulating the amount of the issues by the amount of the capital Mr. GILBART is friendly ; and he suggests the prohi- bition of overdrawn accounts, or advances upon mortgage and other dead securities. To Mr. CLAY'S principle of restricting the liability of the shareholder to the amount of his shares our author is decidedly adverse, and for very cogent reasons: against calling upon bankers for a deposit of stock equal to the amount of notes they issue, he argues like a banker ; but he suggests that the Government might issue debentures analogous to exchequer bills, which should not be transferable, though the Bank of Eng- land might be allowed to make advances on them. He is favour- able to the plan adopted in the defunct Bank of the United States, of having a certain proportion of the directors appointed by the Go- vernment; and, like Mr. LOYD, suggests the adoption of a some- what similar plan in the Government Bank at home. He also recommends several improvements in business and financial details; but he chiefly admires and advocates the adoption of the American system of returns from every bank in the country ; not only for the accumulation of facts, and as a species of check upon the conduct of the banks, but in order to illustrate the state of what Mr. GILBART calls the active and dead circulation, and Which the returns from the Bank of England, however they may be improved, cannot give.

"There is another piece of information which it is desirable to possess reb tire to the circulation of the Bank of England, and it is one which the Bank cannot supply. It is desirable to know the difference in the amount °iof the active circulation and the dead circulation, so as to be able to trace their

's

sn respective fluctuations. That portion of the notes of the Bank of Engl d which is passing from hand to hand, may be called the active circulati That portion which is hoarded, or kept in reserve to meet possible dn:: monde, may be called the dead circulation. Now it is quite certain that the dead circulation, while it remains in that state, has no effect upon the prices° f commodities, the spirit of speculation, or the foreign exchanges. These effected only by the active circulation. In seasons of pressure, the dead circa's_ non is increased at the expense of the active circulation, because people heard their tnoney to meet contingencies. Hence we find the pressure is often niers severe than the reduction of the Bank circulation would seem to warrant. Ent the fact is, that the pressure is in proportion to the reduction of the active circulation, and not in proportion to the reduction of the whole circulation On the other hand, in seasons of abundance, the dead circulation is died,. nished, the active circulation proportionably increased ; and hence the sti. mulus given to trade and speculation is much greater than the returris of the Bank of England would warrant us to expect. Now what means do we pos. sees of getting at the amount of the dead circulation? The Bank of Enema can give us no information on the subject ; but it seems probable that abates all the dead circulation is in the hands of the different banks: very few private individuals keep any hoard of bank-notes. If, then, all the bankers and bash be required to produce returns of the amount of Bank of England notes in their possession, this might enable us to form a judgruent as to the amount of the dead circulation."

There is, however, one species of dead circulation which ette. not be got at, though in unsettled and gloomy times we suspect it is considerable in the aggregate,—and that is the hoarding of gold which takes place by private individuals.

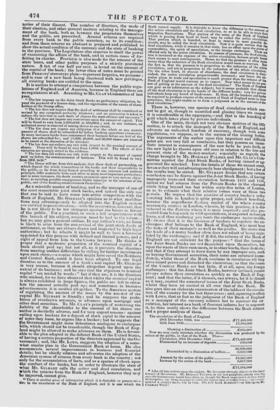

One of the main, though not very obvious motives of the fifth section, is to attack the monopoly of the Bank of England, and advocate an unlimited freedom of currency, though with some regulations, we suppose, as to the nature of the issuing bodies. The arguments of the author upon this important and difficult point are not very full or conclusive, but they possess an imme- diate interest in consequence of the new facts he puts forth, or the new light lie throws upon old ones in relation to the late and present state of the money-market; especially as regards the charge brought by Mr. HORSLEY PALMER and Mr. CLAY'S Com- mitttee against the Joint Stock Banks, of having caused or ag- gravated the mischief. Into the details of these we cannot enter, because they will not advantageously bear abridgment ; beta few of the results may be stated. Mr. GILBART denies that any certain conclusion can be drawn against the Joint Stock Bank!, of having improperly increased their circulation between 1833 and 1836, unless we had returns from the Private Banks in the charmed circle lying beyond ten but within sixty-five miles of London, so as to estimate what their relative issues were at those two periods. He argues that the practice of country bankers redis- counting bills in London is quite proper, and indeed beneficial, because the superfluous flailing capital of the whole country necessarily centres in London, whence, by this practice, it is dis- tributed in the districts where it is most required ; and also pre- vented from being sunk in wild speculations, or exported in foreign loans, and thus rendering pro Santo the exchanges untkvourable. Ho denies that it is the business of bankers to regulate the ex- changes: that belongs to the Bank of England, who must bear the risks of their monopoly as well as the profits. He states that the trade of a cmntry banker often does not admit of being regu- lated by the exchanges ; and if it did, the returns of the Bank of England are not sufficient for tho purpose :* that the issues of the Joint Stock Banks are not dependent upon themselves, but upon the wants of their customers, or in other words, their districts ; and that if they attempt to force them by any improper arts, such as buying Government securities, their notes are returnedimme- diately, whilst those of' the Bank continue in circulation till they have raised prices and disturbed the circulation; so that the issues of the Country Banks act but little, if at all, upon the foreign exchanges: that the Joint Stock Bunks, however inclined, cannot always reduce their circulation as quickly as the Bank of Eng- land; and that the latter, if it chooses, can always, let it be dented as it may, control the unnatural issues of the Joint Stock Banks, whilst they have no control at all over that of the Bank. He also goes into an elaborate examination of the tables of the circula- tion of the country for the last three years ; and, agreeing in effect with Lovn, that as fast as the judgment of the Bank of England as a manager of the currency induces her to contract the ea culation, her interest as a bank of discount induces her to augment it, Inc thus neatly shows the difference between the Bank returns and a proper analysis of them.

The circulation of the Bank of England 28th December 1833, was

£17,469,000 25th June 18:36 Showing a diminution of 17,184,000

£285,000

Now we may easily ascertain whether the diminution was producedby the action of the public, or that of the Bank. Thus— Circulation, 28th December 1833

£17,469,000

Diminished by an increase of deposits

570,000

1699 Diminished by a diminution of bullion 3,8332r00

Amount by the action of the public Increase by the action of the bank 13,567,000 3,617,000

£17,184,000

• Like all late writers upon the subject, Mr. GIT.BART strongly objects to the insuf- ficiency of the returns. Mr. Iloast.vm PALMER. in his last pamphlet, admits this, but says the Government would have them so, though the Bank suggested twit the!, xould be deceptive, (as being invoruplvtc. a ith the appearance of consplilenes•, I an I recent. men led a siinpler mode, but mu vain, 01% are Lord ALTHORP I—at him again, gr. CHARMER WOOD !

Previous page

Previous page