`THERE IS NO SEA IN BAGHDAD'

Charles Glass meets

refugees from the oppressive regime of Iraq

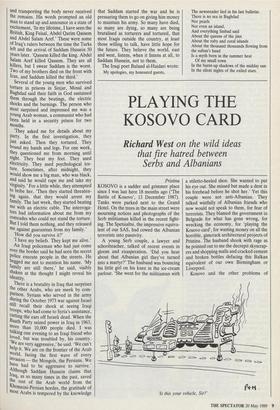

Qamishli, north Syria WHEN we arrived in the village, the old men invited us into one of the houses to sit and drink tea. Like all the other houses in Mizgeft, it was made of mud bricks, had no furniture and consisted of only one room. We sat on the floor, more than 20 men cross-legged and all with backs to the wall, a bedouin tradition that avoided attack from behind. The village elder, who had owned much of their land in the Sinjar hills before his people fled from Iraq, said, 'Let us slaughter a sheep for our visitors.'

`They didn't come here to eat,' my friend told them. 'They came to listen to your story. Don't bring a sheep. Bring people who were in prison. This is your chance to communicate with the Western world.'

I looked round the room at all the expectant faces, old men with long blond hair and beards like the aged Gauls in Asterix, younger men with trim black moustaches, all politely hiding the soles of their feet under their cotton robes. Through me, they would tell the Western world how they and other Iraqis had suffered at the hands of their government in Baghdad, how many of their relations had been killed, how some of them had been tortured. I knew the Western world was unlikely to listen. Why was I wasting their time? When the world saw 5,000 Kurdish civilians massacred by Iraq's che- mical weapons in the northern Iraqi town of Hallabja in 1988, it was silent and inactive. The only reaction from Washing- ton was to raise export credits to Iraq from $805 million to $1.35 billion. The Soviet Union, West Germany, France and Britain maintained their friendly relations with Baghdad. Perhaps, rather than record and report their stories, I should have eaten their sheep and gone quietly home.

Dr Hamad Suaidi, the head of the Iraq Affairs Bureau, said there were 80,000 Iraqi refugees in Syria: Arabs, Kurds and, like the people we were seeing in Mizgeft, Yazidis. Some people called the Yazidis,

derisively and incorrectly, devil- worshippers, because of confusion over a theology combining elements of Zoroas- trianism, Manichaeism, Judaism, Christ- ianity and Islam. The Yazidis from Sinjar

said they had built Mizgeft, a village for about 200 families, in 1988. It looked like most of the other villages in the northern Syrian plain. The day before I came to Mezgeft, I had been to Tel Tamar. It too housed Iraqi refugees, people whose fami- lies had fled in 1923 from Iraqi massacres of Assyrian Christians and not returned. The Yazidis of Sinjar were newer arrivals, who believed they would go home. The village elder, Murad Sheikh-Khodr, re- minded me of a Palestinian refugee re- membering his orange groves near Jaffa. 'I had land with 5,000 fruit trees in the village of S'keeni. I had tractors, trucks and cars. I was born in S'keeni, like my father and grandfather. Then it was erased from the earth by bulldozers.'

He said that when dissidents began taking refuge in the Sinjar hills in the late 1970s, the government in Baghdad des- troyed the villages. Until then his people had supported Saddam Hussein, Iraq's president. 'We were his right hand,' the old man said. 'Then he betrayed us. Our land was confiscated, our honour disgraced, our women raped. The inhabitants of 300 villages were put in ten large villages. To exert their control over us, they put us on the plains. On the plains, we became labourers for others, when we had been our own masters. Every day, they would take some of us away, blindfolded and with our hands tied.'

His sons fled to Syria. 'So', the old man said, 'they arrested me for 22 months. I was with this man.' He indicated another old man in the room. 'And I was with the father of Dr Hamad Suaidi. We were 42 old men in the cell, of whom I was the eldest. Next to us was a cell with old women. We were not allowed to use the toilets. Eight of us died of infection. When the doctor said we were all dying anywaY, they let us go.' Dr Suaidi, whose parents died after leaving the prison, explained, 'They were arrested to pressure their children to re- turn. After 22 months, the children did not return, so they let them go.'

The old people said they had not been tortured. Younger men and women were not so lucky. In a full day at the village, and later in the town of Qamishli, I was told stories and shown scars by dozens of people who had survived Iraq's prisons. They differed not at all from the accounts of Amnesty International's latest report on Iraq — torture of men, women and chil- dren; summary executions; arrests of rela- tions of suspected dissidents; seizure of land and houses; mass deportations; and the use of chemical weapons in violation of international conventions.

Many of the dissidents near the border with Iraq said Syria was permitting them for the first time to launch operations directly into Iraq. Iraq was, after all, arming Syria's enemies in Lebanon and attempting to destabilise the government in Damascus. Despite Syrian support, guerrilla war in Iraq was dangerous. 'It's very difficult now,' said a Kurdish fighter. `Not only the chemical weapons, but there are no people in the countryside.' In the past, governments who knew Mao's dictum about the people being the sea in which the guerrilla-fish could swim would attempt to remove the fish. Saddam Hussein has taken away the whole sea, depopulating the Kurdish countryside and confining Its people to concentration camps and the three large cities.

Syria is taking a risk. Iraq has a larger army with better weapons, and it could begin to hit guerrilla bases and refugee villages along the border. This was the pattern set by the Israelis in south Leba- non, with disastrous consequences for the Palestinians and Lebanese. But Iraq is not Israel. As one Kurd said, talking to me late at night about the Israeli reaction to the Palestinians' intifada in the West Bank and Gaza, 'If Saddam Hussein treated us the way the Israelis treat the Palestinians, we would love him.' One young man in the house at Mizgeft was telling me that bodies of people executed in the prison where he had been held were returned to the families in sealed coffins and that public funerals were not permitted for the victims. He said that families without the money to pay the government the cost of buying the coffin

and transporting the body never received the remains. His words prompted an old man to stand up and announce in a state of excitement, `In my lifetime, I have seen the British, King Feisal, Abdel Qarim Qassem and Abdel Salam Aref.' These were some of Iraq's rulers between the time the Turks left and the arrival of Saddam Hussein 50 years later. `Qassem killed the king. Abdel Salam Aref killed Qassem. They are all killers, but I swear Saddam is the worst. Two of my brothers died on the front with Iran, and Saddam killed the third.'

Several of the young men who survived torture in prisons in Sinjar, Mosul and Baghdad said their faith in God sustained them through the beatings, the electric shocks and the burnings. The person who most surprised and impressed me was a Young Arab woman, a communist who had been held in a security prison for two months.

`They asked me for details about my party. In the first investigation, they Just asked. Then they tortured. They bound my hands and legs. For one week, they questioned me from morning until night. They beat my feet. They used electricity. They used psychological tor- ture. Sometimes, after midnight, they would show me a big man, who was black, and said he would rape me and take my virginity.' For a little while, they attempted to bribe her. `Then they started threaten- ing again, that they would arrest my family. The last week, they started beating me with an electric cable. The interroga- tors had information about me from my Comrades who could not stand the torture. But I told them nothing, and they released me against guarantees from my family.'

`How did you survive it?' I have my beliefs. They kept me alive.'

An Iraqi policeman who had just come over the border said he had seen the secret police execute people in the streets. He begged me not to mention his name. `My family are still there,' he said, visibly shaken at the thought I might reveal his identity. There is a brutality in Iraq that surprises the other Arabs, who are meek by com- parison. Syrians who served in the army during the October 1973 war against Israel still recall their shock at seeing Iraqi troops, p who had come to Syria's assistance, cutting the ears off Israeli dead. When the Baath Party seized power in Iraq in 1963, more than 10,000 people died. I was talking one evening to an Iraqi friend who loved, but was troubled by, his country. We are very aggressive,' he said. 'We can't help it. We are on the frontier of the Arab world, facing the first wave of every Invasion — the Mongols, the Persians. We have had to be aggressive to survive.' Although Saddam Hussein claims that Iraq, as so many times in the past, saved the rest of the Arab world from the Khomeini-Persian hordes, the gratitude of most Arabs is tempered by the knowledge

that Saddam started the war and he is pressuring them to go on giving him money to maintain his army. So many have died, so many are dying, so many are being brutalised as torturers and tortured, that most Iraqis outside the country, at least those willing to talk, have little hope for the future. They believe the world, east and west, listens, when it listens at all, to Saddam Hussein, not to them.

The Iraqi poet Buland al-Haidari wrote: My apologies, my honoured guests,

The newsreader lied in his last bulletin: There is no sea in Baghdad Nor pearls Not even an island, And everything Sinbad said About the queens of the jinn About the ruby and coral islands About the thousand thousands flowing from the sultan's hand Is a myth born in the summer heat Of my small town In the burnt-up shadows of the midday sun In the silent nights of the exiled stars.

Previous page

Previous page