Exhibitions 2

Duncan Shanks (Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, till 31 May)

The Constable of Clydesdale

Laura Gascoigne

Watching the Nine O'Clock News on tilY return from Scotland, where I'd been interviewing the painter Duncan Shanks, I was amazed to hear the name of Aberdeen mentioned. Aberdeen never makes the national news except when its football team draws with Rangers. What had put it up there with Zimbabwe, Longbridge and London's mayoral election? Answer: the weather. Heaviest April rainfall for 60 Years, two inches of it in the previous 24 hours.

It occurred to me that we have reason to thank our climate for giving us more than news items of national importance. It has also given us a great tradition of landscape painting by setting meteorological condi- tions - that only the bravest and the best artists can meet. Landscape painting is never easy, even in the best of weathers, because there is sotaYs too much going on. Most artists e this problem by picture-making: selecting and ordering elements of a view until they have a harmonious composition. In other words, they tidy up reality, sacrific- ting the multiplicity of nature to the the of a unified artistic vision. But in `_'e process they sacrifice the truth. Nature resn't present a united front, as any fool POWs who has ever looked at it: it is con- , autlY pulling, pushing, thrusting, twisting con- ed pulling, .pushing, a hundred different direc- _,L1Pos at once. A unified vision of it, in these ,greomstances, is pie in the sky, and it's a tLiestament to human obstinacy that genera- us of artists have tried to achieve it. But some have opted not to. One was John Constable, who paid dearly for his refusal to tame nature by being made to wait until the age of 52 for election to the Royal Academy. Another is Duncan Shanks, a contemporary Scottish painter who likes to take reality as he finds it and cram it, in all its wild profusion, onto can- vas.

Duncan Shanks doesn't like talking about his work, and he is quite a hard man to pin down. A colourist in the best Scot- tish tradition who draws all the time 'to keep in touch with nature', he defines his pictures as landscapes, but confuses critics by swinging between figuration and abstraction. His 1998 exhibition, Capriccios, at Roger Billcliffe Fine Art in Glasgow, was almost wholly abstract; his present one, at the Scottish Gallery, is what he lightly calls 'illustrative'.

Whether by nature or nurture, Shanks's artistic vision is perfectly suited to the Clydesdale landscape where he was born and still lives. Between the riverside garden of his house near Carluke and the rocky hills, glens and burns that surround it, he finds all the variety necessary to stop him ever wanting to paint elsewhere. And if that were not enough, there is the local weather that changes from hour to hour and from field to field. When Shanks paints rain falling on one half of a picture and not the other, or snow hitting a hillside in a single shaft, it's not artistic licence; it's the truth. I left Glasgow Central for Car- luke with the spring sun shining and the local lasses out in their camisoles. A few stops on, my train passed through a white station. It wasn't a spring wedding, as I thought, but a hailstorm traceable to a sin- gle cloud.

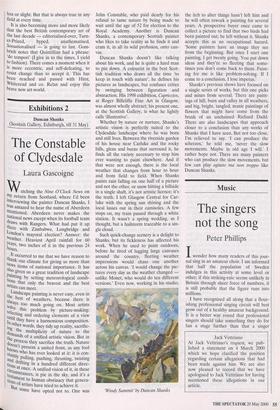

Such quick-change scenery is a delight to Shanks, but its fickleness has affected his work. When he used to paint outdoors, before he tired of lugging large canvases around the country, fleeting weather impressions would chase one another across his canvas. 'I would change the pic- tures every day as the weather changed unlike Monet, who would do ten different versions.' Even now, working in his studio, 'Windy Summit' by Duncan Shanks the itch to alter things hasn't left him and he will often rework a painting for several years. A prospective buyer once came to collect a picture to find that two birds had been painted out; he left without it. Shanks accepts this as an occupational hazard. `Some painters have an image they see from the beginning. But once I start one painting, I get twenty going. You put down ideas and they're so fleeting that some- times you don't come back to them. Paint- ing for me is like problem-solving. If I come to a conclusion, I lose impetus.'

Shanks's previous shows have focused on a single series of works, but this one picks and mixes from several. There are paint- ings of hill, burn and valley in all weathers, and big, bright, tangled, manic paintings of flowers that might have come from the brush of an unchained Richard Dadd. There are also landscapes that approach closer to a conclusion than any works of Shanks that I have seen. But not too close, I'm relieved to say. 'I can produce the scherzos,' he told me, `never the slow movements. Maybe in old age I will.' I rather hope not. There are many painters who can produce the slow movements, but few can play agitato ma non troppo like Duncan Shanks.

Previous page

Previous page