Ends of the Earth

IN 1950, when Professor Edward Winter was engaged in anthropological field-work among the Amba of western Uganda, he had a simple but marvellous idea. He had studied the patrilineal clan-structure of their villages, clustered on the forested floor of the Rift Valley south of Lake Albert, under the Ruwenzoris' towering snows. He had mastered the simplicities of their cash economy (coffee, cotton, plantains and cassava, marketed at Fort Portal over the mountains) and the complexities of their barter one (wives, ex- changed in polygamous quantity for female rela- tives or hire-purchase instalments of goats and fowls). But he felt dissatisfied with such analysis of social mechanisms: the abstraction, it seemed to him, of an abstraction, without that full prior picture of society we derive in literate cultures from novels or plays. So he asked four Amba- two clan elders, and the wives of one of them— to tell their life-stories for him. They poured into the ear of a trusted translator the histories of their families, sexual experience and domestic arrange- ments, and the resulting autobiographies make up Beyond the'Mountains of the Moon (Routledge, 28s.): four private African lives revealed in their own words, and one of the most fascinating documents to come out of Africa for years.

The most interesting data, historically, comes from Kihara, a fifty-year-old hunter who remem- bers the days before the British protectorate. He can recall the war when the Amba were con- quered by the Toro; neighbours who still ate human flesh; an.: poison ordeals for suspected witches,

Witchcraft figures in his thought more than the others': he had to divorce a wife whom he caught putting her head on upside down, and resorted with enormous success to a witch-doctor for a potion to prevent him being conscripted for the Europeans' war. ('They looked at the anus of each of us and said they were not right. Even our testicles were not fit for the army.') But the star of the book is his son-in-law, Mpuga, an African Boswell of thirty-live: welt-meaning, anxious, promiscuous, garrulous and charming. Youngest and richest of the clan elders, he boasts of his Christian learning and his virility; worries about his popularity and health, and bickers end- lessly with his three wives—Lubangi, the senior, whom he married in church, Koke, a tempera- mental trouble-maker, and Kijungu, the latest, sweet and barely twenty. Full of plans for self- improvement, Mpuga dresses them in cotton instead of bark-cloth, and will not let them eat rats or snake-meat, Aruba delicacies sneered at by the Toros. But plantain-beer and love beguile his ambition, and each scheme of betterment founders in a crisis of litigation, expiatory goats and irate wives going home to their families.

But do not come looking for amusing naiveté. There is nothing simple about Koke, the bitter, thieving child of divorce, whose father traded her in marriage to a leper. She escaped, but has not forgiven the world. As children, an envious friend poured water on her first dress. 'You have been looking for me, now you have found me, said Koke exultantly, and fell with her, clawing, into a stream. There are depths, too, behind the plain, still face with which Lubangi keeps the household running. She has Mpuga's ring; she knows of the time he set off with a pretty prosti- tute to see Kampala, the royal city, but lost his nerve and came home with indigestion. But she

has not accepted her life placidly. 'I only watched this,' her story ends painfully, 'because I have no advice to give Mpuga, and because I have failed to stop him marrying other wives.'

Santha Rama Rau's My Russian Journey (Gollancz, 21s.) is interesting for similar reasons. She managed to make friends with Russians and get them talking. Her Russian was not as fluent as that of her husband, an American scholar of the Russian theatre, but she gained some ad- vantages by being Indian—Russians were curious and her own mind was open. She felt no special terror of Socialism, and could look at Moscow with Asian eyes, sharing the Russians' excite- ment in their capital, their sense of it as an Asian, metropolis. Everywhere were Oriental ballets. music and restaurants, welcoming flourishes of eastern taste, so that the farthest Kazakh, Uzbek or Azerbaijani might look on Moscow as his Moscow too. Miss Rau did not feel it hers, but neither did she treat the people she met there as people met to put into a travel-book. One Mos- cow student, closest friend of all, trusted them with his little Soviet tragedy : at twenty he had married a rougeless Komsomol beauty, since the Thaw he found her conventional, earnest, life- less, now he had met a laughing, lovely girl. . . . Miss Rau says, convincingly, that she saw the sil- houette of St. Basil's and the Red Star over the Kremlin fade for the last time in a glowing night sky with a pang of affection and regret; leaving one trying to remember what other non-Com- munist writer can make any approach to such a claim.

Louis Fischer wrote a well-known life of Gandhi. His Story of Indonesia (Hamish Hamil- ton. 30s.) reads as if he may have started eastward with a vacant Mahatma's halo which he found President Sukarno too busy or too volatile to try on. Most of his time in the islands seems to have gone trying to urge the president into serious de- . bate on birth-control or Communism during gay speech-making jaunts by air to Bali, or carefree motorcades up to Bandung to open an Olympic swimming pool. Meanwhile a more or less serious rebellion was taking place in Sumatra and Celebes, Indonesia was becoming Asia's flash- point, and the whirlwind seemed likely to over- throw Sukarno unless he were Mahatma enough to ride it. Well, it's all over now, no one knows quite how, and colonels last heard of in disgrace seem to be walking freely about Djakarta. But there are so few books about Holland's lost green empire that it seems ungrateful to say that Mr. Fischer might have worried less and enjoyed his visit more. Anyway, there is always room for a crisp reminder, such as he supplies in his early chapters, that once upon a time there were half a million white colonists who said their only aim was partnership, who said they had no other home to go to, who said their withdrawal would bankrupt the country, who said no one outside could understand. . . . Where are they now?

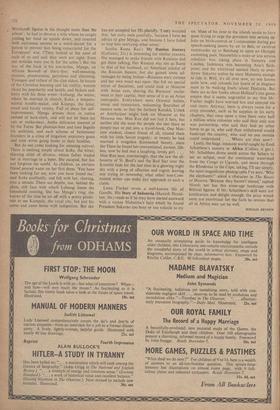

Lastly, the huge, innocent world caught by Emil Schulthess's camera in Africa (Collins, 6 gns.). Mr. Schulthess drove south across the Sahara to see an eclipse, over the continental watershed from the Congo to Uganda, and down through the Rhodesias to the Cape, taking. I'll say simply, the most magnificent photographs I've seen. 'Why the elephants?' asked a character in The Roots of Heaven. 'Because they haven't sinned,' replied Morel; nor has this stone-age landscape with Biblical figures. If Mr. Schulthess's skill were not justification and delight enough. the price would seem not exorbitant for the faith he revives that all in Africa may yet be well.

Previous page

Previous page