The Radical Right

By TELFORD TAYLOR IN any discussion of the American right, McCarthy's symbolic role is inescapable. 'Although his personal influence lasted barely five years—beginning with his famous speech at Wheeling in February, 1950, when he charged that the State Department was rife with Communists—he achieved an impact that made him a global figure, which is why `McCarthyism' remains part of the political lingua franca, a matter of abiding curiosity and concern both within and beyond America's borders. Historians may find its antecedents as far back as 1798, when Federalist Francophobia led to the passage of the Alien and Sedition Laws (paralleled in Britain by the Unlawful Oaths and Unlaw- ful Societies Acts of 1797 and 1799); and nineteenth-century progenitors of rightist ex- tremism include the rabidly anti-Catholic Know-Nothing Party and, of course, the Ku Klux Klan. But the Sedition Laws and the Know-Nothings lie buried in the dust of time, and although the racial issues that spawned the Klan still burn fiercely, the Klan itself no longer counts for much. For all practical purposes, McCarthyism is a product of the last quarter-century.

The year 1938 is a useful beacon. The United States was then emerging from the intense social and economic evolution of the New Deal period, the federal Wage and Hours- Law, enacted in 1938, being the last major piece of New Deal legislation. But also in that year came the first of the big loyalty investigations, conducted by the newly-created House Committee on Un- American Activities under the chairmanship of Congressman Martin Dies.

In America, the tensions and conflicts had been acute between 1935 and 1938, with labour spies and sit-down strikes, sharecroppers and poll taxes, exposures of Wall Street financial skulduggery, and the bitter debate over President Roosevelt's Supreme Court 'packing' plan. These struggles were waged against the background of a deep cleavage of American public opinion: Broadly speaking, there were on the one side those who believed in the use of governmental power to ameliorate social and economic malad- justments, who supported the spread of labour organisations and welcomed the emergence of the unions as a major political force, who were eager to make common cause with democratic governments and parties in other countries to oppose the totalitarian and 'imperialist' regimes —and who, however much or little troubled by the dictatorial and ruthless nature of the Soviet government, were sympathetic to it, and im- pressed with its apparently intransigent hostility to Nazism and Fascism. On the other, there were those who opposed governmental regula- tion of social and economic affairs, believing that natural economic forces would lead to renewed prosperity; who feared that powerful unions would undermine the efficiency of busi- ness management and endanger the health of the body politic; who distrusted allies and alliances, believing that the United States should seek security in her own strength unhampered by 'foreign entanglements'; and who thought Communism a far greater menace than Fascism.

Throughout the Twenties, the laisser-faire- isolationist approach was dominant; but in the Thirties it was overwhelmed by the social wel- fare-internationalist viewpoint, largely as a con- sequence of the Depression and the fears and hatreds generated by the growing power of the Axis dictatorships. The changing tide of public opinion swept first 'rugged individualists' and then `isolationists' into the discard, though some of them were later to band together in strident but ineffective groups such as the America First Committee.

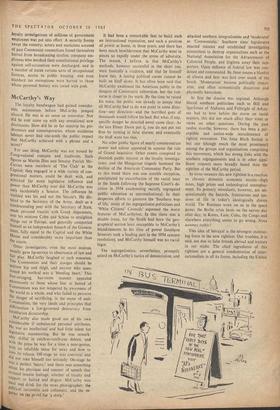

Ten years ago, the late Senator Joseph R. McCarthy was the bellwether of what has since been dubbed the 'radical right.' But the beliefs and emotions of which he was the talisman were widespread long be- fore he became prominent, and today— more than four years after his death—they are again a prominent feature of the American political landscape. The emer- gence of the John Birch Society, and the recent proliferation of comparable groups, suggest that it is timely to examine the origins of the extreme right-wing move- ment in the United States; and we have asked Mr. Taylor—the American lawyer who led for the prosecution at the Nuremberg trials—to discuss and assess their prospects.

In the course of this truly revolutionary shift in public thinking, the Communist Party in the United States was assiduously exploiting the focal issues--industrial unionism, civil rights, aid to Loyalist Spain, embargoing Japanese trade— so as to gain an important voice in the manage- ment of certain unions and organisations of liberal opinion, and to augment the membership of the Party by recruitment from these same circles. The movement which later became known as McCarthyism was in its origin a tactic of discrediting the social welfare-internationalist outlook by exposing and denouncing the con- tacts and connections, actual and alleged, be- tween its adherents and the Communist Party during the period of the United Front.

The initial sponsors of this movement seized on the `red' issue partly from conviction, and partly because it proved an effective weapon against their liberal opponents, as a broad avenue to extensive and sensational publicity. This last feature was especially attractive to legislators; hence the prompt emergence of Congressional loyalty investigations, by com- mittees empowered to subpoena witnesses.

Martin Dies was the first master performer on this instrument, but his vogue was cut short by the war. Because of the Hitler-Stalin pact of August, 1939, the Communist Party loudly up- posed American aid to the Allies and involve- ment in the war. So did Senator Burton Wheeler, Colonel Charles Lindbergh and the other isola- tionist leaders of America First, who thus found themselves in alignment with the Communists, just as the liberals had been during the days of the United Front. After Hitler invaded Russia and Japan attacked Pearl Harbour, the United States and the Soviet Union became partners with Britain in the Grand Alliance again,,t the Axis. Inevitably, public Red-hunting became a thankless undertaking; Dies vanished from the political scene in 1944; and the Un-American Activities Committee went into eclipse.

But the Grand Alliance did not long survive its own victory, and by 1947 events were shaping themselves so as to revive the Congressional loyalty inquisitions and create the atmosphere of disillusionment, suspicion and fear which McCarthy (who had been elected to the Senate in 1946) found so congenial.

Despite all the strain and disappointment of the post-war years, the country as a whole did not swing back to the isolationist' mood of the Twenties. Broadly speaking, the 'Modern Re- publicanism' of the Eisenhower Administration was liberal-internationalist in outlook. But the extreme right wing of both major parties was considerably strengthened during the late Forties, and the laisser-faire-isolationists again laid hold of the weapon Martin Dies had wielded --the Un-American Activities Committee. And in 1950 the Senate established the comparable Sub- committee on Internal Security, headed by the late Senator Patrick McCarran.

A prominent part in the staff work of these committees was taken by ex-Communists, many of whom, despite their defection, retained the doctrinaire, rigid cast of mind which had made them susceptible to the lure of totalitarian ideology. Yet, curiously enough, these new loyalty investigations were launched at the very time when Communism was losing its last vestiges of appeal to liberals, and the Communist Party in the United States was dwindling to numerical insignificance. The collapse of the Axis govern- ments deprived the members of the old United Front of their common foes; social progress and economic prosperity eliminated a number of their common goals. There remained 'peace' and the abolition of atomic weapons, an issue sym- bolised for Communists by the dove and the Stockholm 'peace appeal,' and on this narrower basis a certain amount of 'Communist front' activity, in which some liberals were involved, kept on during the Forties. But the Hitler-Stalin pact and the Russian attack on Finland had driven many liberals from the Party in 1940, and after the suppression of democracy in Czecho- slovakia there was another exodus. By 1950, ac- cording to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Party's membership in the United States was only 43,200, about half the 1944 peak.

Nevertheless, the former Party or 'front' affiliations. of government officials, labour union leaders, teachers and others, remained a fertile and favourite field of Congressional inquiry. The executive branch now exhibited similar symp- toms, and a far-flung, ponderous programme for loyalty investigations of millions of government employees was put into effect. A security frenzy swept the country; actors and musicians accused of past Communist connections found themselves barred from broadcasting studios; company em- ployees who invoked their constitutional privilege against self-accusation were discharged; and in a number of states various sorts of occupational licences, access to public housing and even standard tax exemptions were barred to those whose personal history was tinted with pink.

Previous page

Previous page