Manic quirks

Nicholas Powell

Art should 'make you laugh a bit and cry a bit: everything but bore you'. The son of a wine merchant from Le Havre and one himself until he was 41, Jean Dubuffet was a major and courageous eccentric, an iconoclast who claimed that the Western tradition had got it all wrong and needed a fresh start — with him, of course, doing the starting. This year is the centenary of his birth and is as good a pretext as any for one of those great monographic exhibitions of which the Centre Pompidou is so fond. It is the first retrospective of Dubuffet's work in nearly 30 years.

Laid out very prettily in a succession of different-sized temporary rooms (in pleasing contrast to the terribly bare Stanley Spencer retrospective at Tate Britain earlier this year), the show illustrates every quirky step in the career of a man generally known only for the drab monochrome sculpture of his later years. The drawback is that it contains such vast quantities of art — some 400 works spanning more than 60 years — that you wish the occasional exit had been supplied, enabling you to slip out for a sitdown and a coffee in the mid 1940s, for instance. But no. In the grand tradition of monographic exhibitions, the only way out is forward.

Apart from one early canvas visibly inspired by Cubism — `Cerises au fumeur', 1924 — and six almost naturalistic portraits of the artist's mistress Lili from 1935, which could have been painted by Picabia or de Chirico, Dubuffet's art was always idiosyncratic. It really woke up during the second world war, when he gave up his wine business to paint full-time, simplifying and stylising the forms in his painting and making his palette almost garishly bright. The Centre Pompidou has a wall covered with inside views of Metro carriages, charming, repetitive and rapidly executed, packed with gaily coloured doll-like passengers all smiling as if they did not know that there was a war on. As the war went on, Dubuffet's use of such characters and planes of colour began more and more to resemble the paintings of a child; only after a second and a third look, however, do you seize on the growing sophistication and the adult sense of composition lurking behind the apparent simplicity.

It was after the war, curiously enough, that Dubuffet's palette darkened. Instead of merely applying paint to canvas he also began spreading paste and sand, and gouging outlines in the resultant gunge. He abandoned all pretence of rendering form, portraying flayed, steam-rollered semblances of human portraits such as 'Antonin Artaud aux houppes' or the frighteningly savage `D'hôtel nuance d'abricot' (both 1947). French critics, not surprisingly, likened Dubuffet's work to what they call art brut, the art of the untutored, of the very young and of the mentally ill.

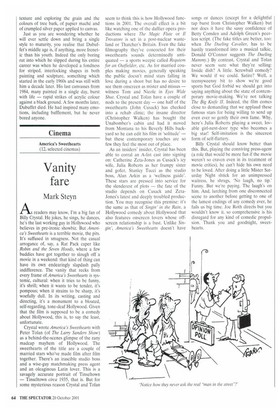

Then Dubuffet took himself off to the Sahara, an experience he loved and which inspired a series of bustling, crammed pictures of Bedouins and the desert: again, pictures that at first sight a child might have produced but on further inspection are far more constructed, more experienced and cleverer. Once back in France, Dubuffet reverted to the steam-rollering process. 'Corps de dame, piece de boucherie', 1950, looks just like that, a female form spread out in one big pink splurge like a well-tenderised veal scallop, her limbs, features and genitals scraped on with childish strokes.

Then Dubuffet became preoccupied with the material effect of paint for its own sake, and for a while dashed into pure abstraction before starting to work, in 1953, with, of all things, butterfly wings, which he glued by the dozen on to a gouache background to create forms suggestive, rather than representative, of human torsos and faces. Papier mache, natural sponges and large clinkers from furnaces were the next materials he used to produce sculptures reminiscent of both the distorted forms and the granular effects of earlier canvasses. Very impressed by the work of Jackson Pollock, Dubuffet executed his own series of drip paintings — which were considerably less confident and duller than those of his model — before returning to his love of texture and exploring the grain and the colours of tree bark, of papier mache and of crumpled silver paper applied to canvas.

Just as you are wondering whether he will ever settle down and bring a single style to maturity, you realise that Dubuffet's middle age is, if anything, more frenetic than his youth. Indeed the only boring rut into which he slipped during his entire career was when he developed a fondness for striped, interlocking shapes in both painting and sculpture, something which started in the early 1960s and was still with him a decade later. His last canvasses from 1984, many painted in a single day, burst with life — rapid strikes of acrylic colour against a black ground. A few months later, Dubuffet died. He had inspired many emotions, including bafflement, but he never bored anyone.

Previous page

Previous page