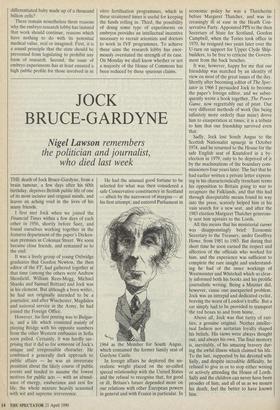

JOCK BRUCE-GARDYNE

Nigel Lawson remembers

the politician and journalist, who died last week

THE death of Jock Bruce-Gardyne, from a brain tumour, a few days after his 60th birthday, deprives British public life of one of its most incisive and original minds, and leaves an aching void in the lives of his many friends.

I first met Jock when we joined the Financial Times within a few days of each other in 1956, shortly before Suez, and found ourselves working together in the features department of the paper's Dicken- sian premises in Coleman Street. We soon became close friends, and remained so to the end.

It was a lively group of young Oxbridge graduates that Gordon Newton, the then editor of the FT, had gathered together at that time (among the others were Andrew Shonfield, William Rees-Mogg, Michael Shanks and Samuel Brittan) and Jock was in his element. But although a born writer, he had not originally intended to be a journalist; and after Winchester, Magdalen and national service in the Army, he had joined the Foreign Office.

However, his first posting was to Bulgar- ia, and a life which consisted mainly of playing Bridge with his opposite numbers from the other Western embassies in Sofia soon palled. Certainly, it was hardly sur- prising that it did so for someone of Jock's unique and irrepressible character. He combined a generally dark approach to public affairs — he was an inveterate pessimist about the likely course of public events and tended to assume the lowest motives for public acts — with an abund- ance of energy, exuberance and zest for life; the whole mixture heavily seasoned with wit and supreme irreverence. He had the unusual good fortune to be selected for what was then considered a safe Conservative constituency in Scotland — albeit by the narrowest of margins — at his first attempt, and entered Parliament in 1964 as the Member for South Angus, which contained the former family seat of Gardyne Castle.

In foreign affairs he deplored the un- realistic weight placed on the so-called special relationship with the United States and the refusal to recognise that, for good or ill, Britain's future depended more on our relations with other European powers in general and with France in particular. In economic policy he was a Thatcherite before Margaret Thatcher, and was in- creasingly ill at ease in the Heath Con- servative Party. Appointed PPS to the then Secretary of State for Scotland, Gordon Campbell, when the Tories took office in 1970, he resigned two years later over the U-turn on support for Upper Clyde Ship- builders, to be free to criticise the Govern- ment from the back benches.

It was, however, happy for me that our friendship was matched by an identity of view on most of the great issues of the day. Shortly after becoming editor of The Spec- tator in 1966 I persuaded Jock to become the paper's foreign editor, and we subse- quently wrote a book together, The Power Game, now regrettably out of print. Our very different methods of work (his being infinitely more orderly than mine) drove him to exasperation at times; it is a tribute to him that our friendship survived even that.

Sadly, Jock lost South Angus to the Scottish Nationalist upsurge in October 1974, and he returned to the House for the safe English seat of Knutsford in a by- election in 1979, only to be deprived of it by the machinations of the boundary com- missioners four years later. The fact that he had earlier written a private letter express- ing in his characteristically trenchant terms his opposition to Britain going to war to recapture the Falklands, and that this had through disreputable means found its way into the press, scarcely helped him in his vain search for a new seat, and after the 1983 election Margaret Thatcher generous- ly sent him upstairs to the Lords.

All this means that his ministerial career was disappointingly brief: Economic Secretary to the Treasury, under Geoffrey Howe, from 1981 to 1983. But during that short time he soon earned the respect and affection of the officials who worked for him, and the experience was sufficient to complete the rare insight and understand- ing he had of the inner workings of Westminster and Whitehall which so clear- ly informed both his books and his prolific journalistic writing. Being a Minister did, however, cause one unexpected problem. Jock was an intrepid and dedicated cyclist, braving the worst of London's traffic. But a car simply had to be provided to transport the red boxes to and from home.

Above all, Jock was that rarity of rari- ties, a genuine original. Neither intellec- tual fashion nor sectarian loyalty shaped his beliefs. His views were always thought out, and always his own. The final memory is, inevitably, of his amazing bravery dur- ing the awful illness which claimed his life. To the last, supported by his devoted wife Sally, and despite incredible difficulty, he refused to give in or to stop either writing or actively attending the House of Lords. Sally and the children can never have been prouder of him; and all of us as we mourn his death, feel the better to have known him.

Previous page

Previous page