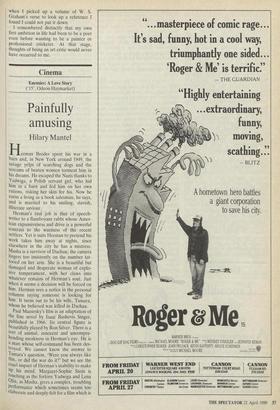

Cinema

Enemies: A Love Story (`15', Odeon Haymarket)

Painfully amusing

Hilary Mantel

Herman Broder spent his war in a barn and, in New York around 1949, the savage yelps of searching dogs and the screams of beaten women torment him in his dreams. He escaped the Nazis thanks to Yadwiga, a Polish servant girl, who hid him in a barn and fed him on her own rations, risking her skin for his. Now he earns a living as a book salesman, he says, and is married to his smiling, slavish, illiterate saviour.

Herman's real job is that of speech- writer to a flamboyant rabbi whose Amer- ican expansiveness and drive is a powerful contrast to the wariness of the recent settlers. Yet it suits Herman to pretend his work takes him away at nights, since elsewhere in the city he has a mistress. Masha is a survivor of Dachau; the camera lingers too insistently on the number tat- tooed on her arm. She is a beautiful but damaged and desperate woman of explo- sive temperament, with her claws into whatever remains of Herman's soul. Just when it seems a decision will be forced on him, Herman sees a notice in the personal columns saying someone is looking for him. It turns out to be his wife, Tamara, whom he believed was killed in Dachau.

Paul Mazursky's film is an adaptation of the fine novel by Isaac Bashevis Singer, Published in 1966. Its central figure is beautifully played by Ron Silver. There is a sort of animal, innocent and uncompre- hending meakness in Herman's eye. He is a man whose self-command has been des- troyed. We cannot know the answer to Tamara's question, 'Were you always like this, or did the war do it?' but we see the cruel impact of Herman's inability to make up his mind. Margaret-Sophie Stein is touching as the forlorn Yadwiga and Lena Olin, as Masha, gives a complex, troubling Performance which sometimes seems too elaborate and deeply-felt for a film which is beset by flippancy, despite its ambition. The most outstanding performance comes from Anjelica Huston. She endows the wife Tamara with a bitter vivacity, and the screenplay gives her the best lines.

Herman has a genius for making a bad situation worse. He ends up married to three women, dangling between tragedy and farce. No wonder that the film's chief problem is that of tone. When we have heard Tamara cry out in the night for her dead children, or describe how, with a bullet in her hip, she escaped death by hiding in a heap of corpses, can we give way to giggles at the bits of sit-com business with which Mazursky has deco- rated his sober theme? We can, but not without feeling extremely uncomfortable. It is not that humour itself is misplaced. A gentle scene in a Jewish country club works very well, but the problem is that the film insists on thrusting jollity on to situations which are only bitterly, painfully amusing. Later, where wit would have been in place, the film takes up pantomime she's-behind- you conventions. It seems particularly crass to turn the Polish wife into a figure of fun.

Complications predictably multiply. The film's atmosphere becomes oppressive, and ponderous. With such actors on hand, Mazursky does not need to repeat his points. The most dangerous theme with which he engages himself is that of the survivors' pull to suicide. An urge to self-destruction breaks through the surface of their new lives. Herman and Masha's sexual voracity is that of people who expect no tomorrow. Here again, the film leaves us uneasy because it is both intelligent and moving in parts, but has found no way to reconcile its general and its personal themes. Men are the same the world-over, it seems to tell us, yet this piece of universal jauntiness sits uneasily with the dismal particulars of Jewish history.

Previous page

Previous page