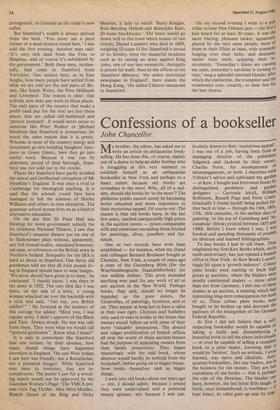

Confessions of a bookseller

John Chancellor

My brother, the editor, has asked me to write an article on antiquarian book- selling. He has done this, of course, mainly out of a desire to help an elder brother who is struggling at this very moment to establish himself as an antiquarian bookseller in New York and perhaps to a lesser extent because old books are nowadays in the news. Why, all of a sud- den, should old books be 'in the news'? The philistine public cannot surely be becoming better educated and more responsive to their mysterious appeal. Of course not. The reason is that old books have, in the last few years, reached unexpectedly high prices in the auction rooms — prices comparable with and sometimes exceeding those fetched for paintings, silver, jewellery and fur- niture.

One or two records have even been established — for instance, when my friend and colleague Bernard Breslauer bought at Christies, New York, a couple of years ago a copy of the Gutenberg Bible (for the Wuerttembergische Staatsbibliothek) for two million dollars. This price exceeded anything ever paid for any work of art at any auction in the New World. Perhaps books, they said, should no longer be regarded as the poor sisters, the Cinderellas, of paintings, furniture, and so on. They appear at long last to have a value in their own right. Christies and Sothebys only used to take in books in the hopes that owners would follow up with some of their more 'valuable' possessions. The absurd and vulgar proliferation of branch offices all over the world of these auction houses had the purpose of separating owners from their family possessions. They began reassuringly with the odd book, whose absence would hardly be noticed from the bookshelf, before going on to bigger things. Now books themselves rank as bigger things.

I went into old books about ten years ago — not, I should admit, because I sensed they were undervalued and a potential money spinner, nor because I was par-

ticularly drawn to their 'mysterious appeal'. I was out of a job, having been fired as managing director of the publishers Sidgwick and Jackson by their owner, Charles Forte, for incompetence or mismanagement, or both. I therefore took Voltaire's advice and cultivated my garden — at Kew. I bought and borrowed books by distinguished gardeners and garden designers — Gertrude Jekyll, William Robinson, Russell Page and Peter Coats. Gradually I found myself being pulled fur- ther back in time — through the 19th, 18th, 17th, 16th centuries, to the earliest days of painting, to the era of Gutenberg and 'In- cunabula' (books printed between 1455 and 1500). Before I knew where I was, I was hooked and spending thousands of pounds on abstruse and learned bibliographies. To buy books I had to sell them. Thus originated my firm Kew Books which, on Its tenth anniversary, has just opened a branch office in New York. At Kew Books I unwit- tingly hit upon a 'growth industry'. Colour plate books were starting to fetch high prices at auctions, where the bidders were mostly continental dealers — more often than not from Germany. I met one of these dealers at an auction, a meeting which had interesting long-term consequences for both of us. These colour plate books were bought to be broken up and decorate the parlours of the bourgeoisie of the German Federal Republic. At first I did not believe that a self- respecting bookseller would be capable of taking a knife and dismembering 3 beautiful book to sell the plates individuallY — or even be capable of selling a complete book to a print dealer, knowing that it would be 'broken'. Such an attitude, I soon learned, was naive and idealistic. Anti- quarian booksellers, like any traders, are In the business for the money. They are not custodians of old books — that is perhaps the role of the librarian. The idealist can have, however, the last bitter little laugh. A book, once dismembered, is worthless — if kept intact, its value goes up year by year'

Those slimy little opportunistic print dealers make a quick buck, but only one; and they have or should have weighing on their consciences those carcasses of letter- Press and cloth or leather from which the plates were ripped. In Germany these print dealers have infiltrated, indeed nearly taken over, the Antiquarian Booksellers' Associa- tion. In the USA they have up to now been kept out. I don't know about England there the 'breaking up' mania does not seem to have reached its uncontrollable continental proportions.

Be all that as it may, the colour plate book par excellence was the botanical book. The 'Golden Age' of the illustrated flower book was at the end of the 18th cen- tury. The French, e.g. Redoute, were, of course, pre-eminent, but there were also some good English botanical artists. They were generally employed to illustrate serial works or magazines published, more often than not, by some prosperous nurseryman. The most famous of these publications is Curtis' Botanical Magazine, affectionately known as the Bot Mag by dealers.

William Curtis was a nurseryman at Hammersmith and his nursery was fre- quented by aristocrats and by members of the upper classes with horticultural propen- sities. In his own words, his magazine, Published in about 1880, was intended 'for the use of such ladies, gentlemen and gardeners as wish to become scientifically acquainted with the plants they cultivate.' I Possess the first 99 volumes of the Bot Mag, for which I want £15,000. For this escala- tion in their value we must thank the Swiss and German 'table mat market'. The smallish plates are just the right size to be cut up, mounted and laminated for the din- ing room table. The Bot Mag had many im- itators and emulators with names such as the Botanical Register, Cabinet, Repository, Flower Garden and so on, all today candidates for the table mat market.

If the Bot Mag has shown itself to be a good investment, the same cannot be said of all old books. Lord Rothschild, who has or had a distinguished collection of books on 18th-century literature (first editions of Pope, Swift etc) wrote an article for The Times fairly recently which showed that, When comparing what he had paid for cer- tain books 20 years or more ago and their Present market (i.e. auction) value, he had actually lost money. If I remember right, the epistolary novel has, for some reason or other, plummeted in value — perhaps because only a few conscientious people like myself, as I tell my children and my brother, bother to write letters nowadays. The genuine book collector and book lover is happy to hear that people burn their fingers when buying books as an 'invest- !tent shelter'. This will teach them to buy books in future for the right reasons, or Perhaps not at all.

Who are these book lovers, and where are they, and are there enough of them to create a viable business? I anxiously ask myself this rhetorical question — nowadays With increasing frequency. Book dealers have got it into their heads that there are in the whole world no more than collectors of rare books and that this number dwindles when times are hard and money scarce. Then the poor book dealer has many books on his shelves but nothing for his next meal. Fortunately in New York there is always Burger King — the home of the Big Whop- per — to keep the wolf from the door.

If the book collecting market is so small, this partly explains a particularly unattrac- tive feature of many antiquarian booksellers and that is a kind of constipated terror of disclosing to colleagues the names of their customers — or clients, as some dealers pretentiously call them. Booksellers are parasites — they grow fat on the custom of a single rich collector, the loss of whom could mean the loss of half his business. In other words, many have all their eggs in very few baskets.

The young emerging booksellers of today are, I am told, more relaxed and open than their elders. They are also looking for custom outside traditional book-collecting circles. They travel far and wide, they hustle

in Dallas, in Riyadh, in Hong Kong and Johannesburg, they stage exhibitions in smart hotels, they claim to bring culture to the uncultured New Rich in the form of expensive colour plate books, books which require no faculty other than the eye to be appreciated and which can im- press with their size and lavishness. To open up successfully such a new book buying market needs youth, vitality, sex appeal and expertise, qualities which I lack. I am not, however, eating my heart out with jealousy at the success of my youthful com- petitors. Instead I shall try and beat them at their own game in a different field with less effort and fewer expenses. I am thinking of the promising market offered by the New York widows and divorcees who have money to spend and little to do. They may provide a fertile hunting ground for a silver- haired, middle-aged, divorced bookseller, or maybe not. They may echo the words of the literary editor of New York magazine who, after coming to the opening of my New York book gallery, wrote to a friend in London about me, saying, 'He's strange'.

Previous page

Previous page