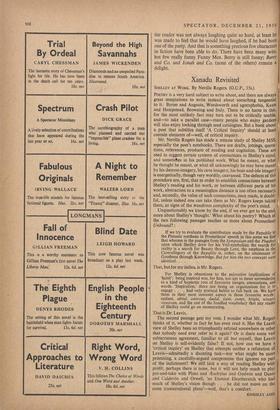

Xanadu Revisited

SHELLEY AT WORK. By Neville Rogers. (O.U.P., 35s.) POETRY is a very hard subject to write about, and there are always great temptations to write instead about something tangential to it: Byron and Augusta, Wordsworth and agoraphobia, Keats and Hampstead, Browning and Italy. There is no harm in this, for the most unlikely fact may turn out to be critically usable, and—to take a parallel case—many people who enjoy garden will also enjoy looking through seed catalogues. But a hook about a poet that subtitles itself 'A Critical Inquiry' should at least contain elements of—well, of critical inquiry.

Mr. Neville Rogers has made a minute study of Shelley MSS, especially the poet's notebooks. There are drafts, jottings, quota• tions, references, products of reading and cogitation. These are

used to suggest certain systems of connections in Shelley's mind,

and sometithes in his published work. What he meant, or what he thought he meant, or what all unknowingly he may have meant

by his daemon-imagery, his cave imagery, his boat-and-isle imagery is energetically, though very wordily, canvassed. The defects of this

procedure are, first, that in order to establish connections between Shelley's reading and his work, or between different parts of his work, abstraction to a meaningless distance is too often necessary, and, secondly, the value of such connections, once made, is doubt- ful, unless indeed one can take them as Mr. Rogers keeps taking I

them, as signs of the wondrous complexity of the poet's mind. t

Unquestionably we know by the end, if we ever get to the end, more about Shelley's 'thought.' What about his poetry? Which of the two following passages teaches us more about Prometheu Unbound? : If we try to evaluate the contribution made by the Republic to the Platonic synthesis in Prometheus' speech in this scene we find that whereas in the passages from the Symposium and the Phcedrac upon which Shelley drew for his Veil-symbolism the search for reality is a search for Beauty through Love, the emphasis in the Cave-allegory of the Republic is, rather, on the attainment of Goodness through Knowledge. But for hitn the two concepts were identical. . . .

That, but for my italics, is Mr. Rogers.

For Shelley is obnoxious to the pejorative implications of 'habit': being inspired was, for him, too apt to mean surrendering to a kind of hypnotic rote of favourite images, associations, and words. 'Inspiration,' 'there not being an organization for it to engage . . . , had only poetical habits to fall back on. We have 'them in their most innocent aspect in those favourite words radiant, aerial, odorous, dtedal, faint, sweet, bright, winged, -inwoven, and the rest of the fondled vocabulary that any reader of Shelley could go on enumerating.

That is Dr. Leavis.

The second passage gets my vote. I wonder what Mr. Rogers thinks of it, whether in fact he has even read it. Has the Leavis

view of Shelley been so triumphantly refuted somewhere or other that nobody need ever refer to it again? Or is there some vast subterranean agreement, familiar to all but myself, that Leavis on Shelley is self-evidently false? If not, how can we have a 'critical inquiry' on Shelley that attempts neither a refutation of Leavis—admittedly a daunting task—nor what might be mor promising, a carefully-argued compromise that ignores no part of the indictment? We still lack a way of reading Shelley with profit; perhaps there is none, but it will not help much to play put-and-take with Plato and fEschylus and Godwin and Dante and Calder6n and Orwell, 'an Etonian Eleutherarch who had much of Shelley's vision though . . . he did not move on th

same transcendental plane'—well, that's a comfort.

KINGSLEY AML

Previous page

Previous page