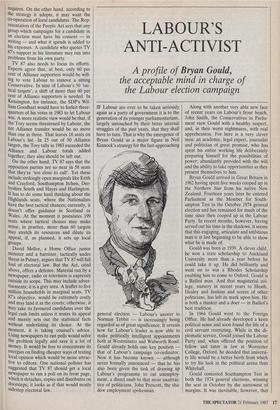

LABOUR'S ANTI-ACTIVIST

the acceptable mind in charge of the Labour election campaign

IF Labour are ever to be taken seriously again as a party of government it is to the generation of its younger parliamentarians, largely untouched by their bitter internal struggles of the past years, that they shall have to turn. That is why the emergence of Bryan Gould as a major figure in Neil Kinnock's strategy for the fast-approaching general election — Labour's answer to Norman Tebbit — is increasingly being regarded as of great significance. It reveals how far Labour's leader is now able to make politically intelligent appointments both at Westminster and Walworth Road. Gould already holds one key position that of Labour's campaign co-ordinator. Now it has become known — although never formally announced — that he has also been given the task of drawing up Labour's programme to cut unemploy- ment, a direct snub to that most unattrac- tive of politicians, John Prescott, the sha- dow employment spokesman. Along with another very able new face of recent years on Labour's front bench, John Smith, the Conservatives in Parlia- ment view Gould with a healthy respect, and, in their worst nightmares, with real apprehension. For here is a very clever man: an academic, legal expert, journalist and politician of great promise, who has spent his entire working life deliberately preparing himself for the possibilities of power; abundantly provided with the will and the ability to take opportunities as they present themselves to him.

Bryan Gould arrived in Great Britain in 1962 having spent five weeks cooped up in the Northern Star from his native New Zealand. Fourteen years later he entered Parliament as the Member for South- ampton Test in the October 1974 general election and has remained for much of the time since then cooped up in the Labour Party. In recent months, however, having served out his time in the shadows, it seems that this engaging, articulate and ambitious man is at last beginning to be able to show what he is made of.

Gould was born in 1939. A clever child, he won a state scholarship to Auckland University more than a year before he could take it up. He did brilliantly and went on to win a Rhodes Scholarship enabling him to come to Oxford. Gould is a Balliol man. And that magisterial col- lege, nursery in recent years to Heath, Healey and Jenkins and scores of other politicians, has left its mark upon him. He is both a thinker and a doer — in Balliol's best tradition.

In 1964 Gould went to the Foreign Office. He had already developed a keen political sense and soon found the life of a civil servant restricting. While in the di- plomatic service, Gould joined the Labour Party and, when offered the position of fellow and tutor in law at Worcester College, Oxford, he decided that universi- ty life would be a better berth from which to try his luck in the political arena than Whitehall.

Gould contested Southampton Test in both the 1974 general elections, winning the seat in October by the narrowest of margins. It was inevitable, however, that he would lose the seat in 1979 and, now with a good track record as a hard-working and effective tribune of the people, he joined the travelling circus of former Mem- bers looking for a safer seat for the future. He was selected by Dagenham — although he continues to live in the comfort of pastures near Henley — and in 1983 he came back to Parliament with a healthier majority. In his years away from West- minster he had added another string to his bow, this time as a television presenter/ reporter for TV Eye. He has also been a regular columnist for the Guardian and written for the Times.

His rise in the present Parliament has been extraordinary, chiefly to be seen in terms of votes achieved in the annua election to the Shadow Cabinet. Most candidates who put themselves forward can expect to add only a few votes a year, creeping up the little ladders while hoping to avoid the large snakes which somehow always seem to take them right back to the beginning of the board. Gould, however, found the main ladder, and in 1986 he passed into the top 15 and a place in the Shadow Cabinet.

In recent months Neil Kinnock has chosen him for three of Labour's most politically sensitive positions: as campaign co-ordinator, as organiser of Labour's plans for cutting unemployment, and as Roy Hattersley's deputy with a particular brief to shadow the Chief Secretary to the Treasury in the Chamber. This was a shrewd move on Kinnock's part because Robin Cook, the previous campaign co-ord- inator, also a very competent but not so popular man, had worked diligently away in Labour's backrooms and suffered great- ly from not being able to shine on the front bench. Kinnock has marked Gould out as a man whose political future he is prepared to promote and he, like many others, will have been impressed with Gould's per- formance as a spokesman on Department of Trade and Industry affairs. Gould has a safe pair of hands. But he is also a lucky man. Lloyd's, Land-Rover, various mono- polies and mergers rows and City regula- tion were delivered up to him as opposition spokesman. Above all, however, was the protracted and complicated passage of the Financial Services Bill during which, curiously, both Gould and the Govern- ment's chief performer, Michael Howard, advanced their reputations.

Gould is the man who in April 1985 greeted the White Paper which was the basis of the 1986 Financial Services Act with the advice that there needed to be tougher statutory controls of the City's business — in its own interests, he ex- plained — than the Government envisaged and indeed later enacted. In April 1985 he said, 'It is inevitable that there will be City scandals arising over the next couple of years. Even on purely political grounds I think that the Secretary of State will rue the fact that he failed to take the opportun- ity.' As shadow to the Chief Secretary, Gould has the task of sorting out the muddle that Hattersley got into over pric- ing out Labour's proposed economic poli- cies. It cannot be long before we hear the whisper that poor old Roy might do better in home affairs, in foreign affairs, in almost any other affairs at all . . . and shouldn't that able fellow Gould be given the chance?

Gould is treated seriously by the finan- cial institutions: one of the very few Labour politicians that the board-room wants to have to lunch. Here is a realist for the Labour Party, one of the new hopefuls who have come to terms with the implic- tions of the permanent success of Mrs Thatcher's government. Gould's one ma- jor book so far, Socialism and Freedom, shows that he has done his thinking in those areas where the Conservatives have changed the argument. It is an impeccably dull volume, but carefully drawn together to display his left-wing credentials while arguing a case in the new language of the post-1983 political world.

In so far as he can be pinned down and he doesn't like to be — Gould is a Peter Shore man. He was, in his first Parliament, PPS to Shore, and was sacked by Callaghan as such, due to his opposition to harmonisation of tariffs in the EEC. Gould comes from an island race and is vehemently anti-Common Market. Shore showed his support for him by labouring on without a PPS at all, and Gould repaid the gesture by supporting his former master in the leadership struggle when Michael Foot stood down.

In 1983, Gould announced that his party `must do some new thinking about princi- ples as well as policies'. He is, as he has said himself, 'a realist in terms of Labour's political decline'. It is clear that his views will not endear him to the far Left. In his braver moments he shows that he knows what needs to be done with Labour's lunatic fellow travellers. To him the word `activist', always used in his writing in protective inverted commas, stands for all that is wrong in the contemporary Labour Party. He means to help make Labour a modern political party.

Where will this ambitious man finally come to rest? He is already much in demand outside the House. When Brian Walden let it be know that he had had enough of Weekend World, Gould was offered the job. He did not want it: 'Of course the money would be nice,' he admitted, 'but I see my career in politics.' Were Neil Kinnock ever to find himself in the unlikely position of taking up residence in Downing Street there would be a real chance that Gould would, sooner or later, become his immediate neighbour, or he could reasonably expect the Department of Trade and Industry. But, if Kinnock fails, and with the prospect of many more `activists' on the Labour benches in the next Parliament, Gould's eventual future might well be outside Westminster. Labour in a terminal shambles will not want or deserve Bryan Gould and he would do well in, say, the World Bank.

Previous page

Previous page