THE BEST GERMANY WE'VE GOT

Timothy Garton Ash discusses German attitudes to Europe

`CE qui parle Europe a tort,' said Bis- marck. Yet since 1945 the Germans have talked almost nothing but Europe. In part this has been the pursuit of national interest in European guise, which is was what Bismarck meant by his remark. As the conservative historian Michael Sturmer has written, 'The only opportunity left to Germany [after 19451 was to play the Western game, to be the most European nation among the European, and to trans- late Germany's geostrategic position into political negotiation power.' The ladder out of the morass was marked 'Europe'. Almost dialectically, Germany had to sac- rifice her sovereignty in order to regain it.

Yet it would be a travesty to treat post-war German Europeanism as merely instrumental. Anyone who knows Ger- many, even superficially, will have encoun- tered there men and women with an emotional, intellectual and political com- mitment to Europe rarely encountered elsewhere. There are, of course, many different versions of this commitment,

varying with generation, region, religous denomination and intellectual tradition. A young Catholic Rhinelander will have one kind, a middle-aged Prussian Huguenot another. In the early post-war years this was often a sort of emotional substitute patriotism: Vaterland Europa. For younger generations it may be a less passionate second identity. But it also flows from a deeper reflection on the course of German and European history.

People from both sides of the main- stream of West Germany politics will make the following argument: what culminated in the new thirty years war from 1914 to 1945 was the folly of the rivalry between European nation states. Germany was only the most extreme example of a more general European phenomenon. It was not just the Hitlerite Reich that was fun- damentally discredited in 1945, not just the Wilhelmine or Bismarckian Reich. No, it was the very idea of the European nation- state. So instead, we should have federal- ism: a federal republic and a federal Europe. Federalism means the opposite of centralism. Power should be devolved both downwards, to the individual Lander, and upwards, to a European government, courts and parliament. In this way we will have a double insurance against any temptation to repeat the mistakes of the past. I present the argument in a very simple form. It was never unchallenged. Yet there is no doubt that this was a leitmotif of West German politics for the last 45 years.

Now, however, we are in a dramatically new situation. Throughout this whole period — until last week, to be precise one might say that Germany needed Europe as much as it wanted it. Needed it, first to secure the basic rehabilitation and restored (though still limited) sovereignty of Western Germany, then as a secure framework of support for the sustained attempt to reduce and overcome the divi- sion of Germany, and restore sovereignty (and liberty) to what we have come to call East Germany. This has now been achieved, at quite fantastic speed. The extraordinary agreement reached between Chancellor Kohl and President Gorbachev in Stavropol declares that 'a reunited Ger-

many, exercising unlimited sovereignty, may freely decide which alliances or blocs it wants to belong to'.

Of course it would be absurd to say that Germany will no longer need Europe. Self-evidently it will. Whatever new econo- mic horizons may open in the East, far and away its largest market will still be here. It would be both difficult and pointless to try to dismantle the whole large, dense net- work of West European integration and co-operation that already exists. But it is not absurd to say that the new, united Germany will now need Europe less for the pursuit of its own particular national in- terests. If the new constellation in the East persists, if this German-Soviet agreement is followed next year, as is firmly planned, by a new comprehensive treaty of a kind we are told — never before seen in East-West relations, then Germany will have a certain strategic choice in Europe.

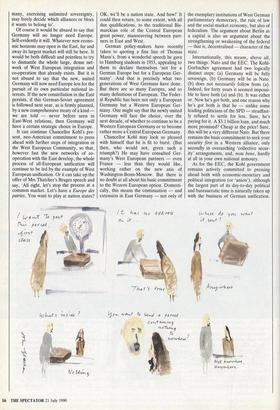

It can continue Chancellor Kohl's pre- sent, neo-American commitment to press ahead with further steps of integration in the West European Community, so that, however fast the new networks of co- operation with the East develop, the whole process of all-European unification will continue to be led by the example of West European unification. Or it can take up the offer of Mrs Thatcher's Bruges speech and say, 'All right, let's stop the process at a common market. Let's have a Europe des patries, You want to play at nation states?

OK, we'll be a nation state. And how!' It could then return, to some extent, with all due qualifications, to the traditional Bis- marckian role of the Central European great power, manoeuvring between part- ners in East and West.

German policy-makers have recently taken to quoting a fine line of Thomas Mann's, from a wonderful speech he gave to Hamburg students in 1953, appealing to them to declare themselves 'not for a German Europe but for a European Ger- many'. And that is precisely what two generations of West Germans have done. But there are so many Europes, and so many definitions of European. The Feder- al Republic has been not only a European Germany but a Western European Ger- many. One might say that the newly united Germany will face the choice, over the next decade, of whether to continue to be a Western European Germany or to become rather more a Central European Germany.

Chancellor Kohl may look so pleased with himself that he is fit to burst. (But then, who would not, given such a triumph?) He may have consulted Ger- many's West European partners — even France — less than they would like, working rather on the new axis of Washington-Bonn-Moscow. But there is no doubt at all about his basic commitment to the Western European option. Domesti- cally, this means the continuation — and extension in East Germany — not only of

the exemplary institutions of West German parliamentary democracy, the rule, of law and the social market economy, but also of federalism. The argument about Berlin as a capital is also an argument about the strengthening or weakening of the federal — that is, decentralised — character of the state.

Internationally, this means, above all, two things: Nato and the EEC. The Kohl- Gorbachev agreement had two logically distinct steps: (a) Germany will be fully sovereign, (b) Germany will be in Nato. (b) does not necessarily follow from (a). Indeed, for forty years it seemed impossi- ble to have both (a) and (b). It was either or. Now he's got both, and one reason why he's got both is that he — unlike some leading politicians of the SPD — steadfast- ly refused to settle for less. Sure, he's paying for it. A $3.1 billion loan, and much more promised? Cheap at the price! Sure, this will be a very different Nato. But there remains the basic commitment to seek your security first in a Western alliance, only secondly in overarching 'collective secur- ity' arrangements, and, nota bene, hardly at all in your own national armoury.

As for the EEC, the Kohl government remains actively committed to pressing ahead both with economic-monetary and political integration (or 'union'), although the largest part of its day-to-day political and bureaucratic time is naturally taken up with the business of German unification. This is neither a necessary commitment, nor does it self-evidently flow from nation- al self-interest, narrowly defined. In his now infamous remarks, published in last week's Spectator, Mr Nicholas Ridley sug- gested that economic and monetary union (EMU) would further strengthen Ger- many's dominant economic position in Europe. Seen from Germany, it is not all clear that this is so. The most favourable option for German industry might actually be to remain at Delors"stage one', with pegged exchange rates, but no European Federal Bank. Herr Pohl has been quite ambivalent about the prospect of a Eurofed. Indeed, the British Treasury felt it had grounds to hope that it would find allies in Germany for its opposition to a single currency. As for German public opinion, a recent poll in The European showed that the Germans were the least enthusiastic of all about a single European currency. (The weaker your currency the greater your enthusiams; the most enthu- siastic of all were the Russians.) In short, the rationale for EMU is a political one, and an all-European economic one, rather than a German economic one.

If one broadens the focus to include political integration, then the Ridley pic- ture looks even more distorted. In fact, back-to-front. Germany has not become more powerful because of political integra- tion in the EEC. Germany has become more powerful because it is very indust- rious, very rich, and now, with unification, very large and very central as well. In the past, German Europeanism was both a long-term, national strategy for the recov- ery of sovereignty and a much more disinterested commitment to share that sovereignty, even while recovering it, in order precisely to prevent the recurrence of that ultimate folly of the European nation-state which was the German drive for domination. Now, with full sovereignty as good as recovered, what remains is the commitment: the offer to share national sovereignty and limit national power, through the EEC and Nato. Naturally this involves some loss as well as gain for everyone involved. Naturally there are profound worries about how power is to be shared, and the democratic accountability of European institutions. But the idea that this is part of some drive for a German Europe is really wild. The agenda this comes from is still that for a European Germany.

If there is a worry, it is not that the new Germany will become more committed to West European integration, but rather that it will become less so. It is no accident that most East European governments, who have far more cause than we to worry about the sudden growth of German pow- er, are strongly supportive of the process of West European integration. One day, with a different government in Bonn — or rather, Berlin — the offer might simply no longer be there.

Previous page

Previous page